Sponsored By: Tweet Hunter

This essay is brought to you by Tweet Hunter, the tool for growing your Twitter audience in just 5 minutes per day. Tweet Hunter helps you create high-performing content and turn those likes and replies into business results.

Chris Dixon is famous for writing, “What the smartest people do on the weekend is what everyone else will do during the week in 10 years.” If you want a glimpse of what you’ll be doing during the week in 10 years, you’ll find a lot of it on Linus Lee’s laptop.

Linus is an independent researcher focused on building better interfaces for people to interact with generative AI models. He wants to replace today’s prompt-based interfaces with affordances that provide greater predictability and control—things like pinch-to-zoom or drag-and-drop interactions for AI.

It’s important research, and his output is wildly prolific because his workflow is a loop. He researches generative AI, and uses what he discovers to build AI tools that will help him think better and get more done. He uses publicly available AI tools as well as a suite of custom-built models that help him read faster, search through information more quickly, and take better notes.

I originally noticed him because he kept dropping fascinating demos of research projects on Twitter. This one, for example, allows a user to make an example sentence longer or shorter by dragging it in different directions. Another one lets him easily explore style variations for Stable Diffusion prompts with just a click or two. A final one lets him visually explore changing a sentence across multiple dimensions—like increasing its positivity or its politeness.

Perhaps it’s this tight coupling that makes him such a good researcher. He’s both a user and a fan of these tools—and that gives him access to problems, and ways to solve them that others might miss.

Lee has granted us access to take a look at the suite of tools he uses to get his work done. Are you ready to peek at what it looks like to live with AI?

Let’s dive in.

Building an audience can be one of your greatest assets but it takes a lot of time and effort.

Introducing Tweet Hunter, the #1 tool to help you get results on Twitter while staying productive and focused on your day-to-day activities. Create better content and drive more opportunities from Twitter in just 5 minutes per day.

Here’s what you’ll be able to do with Tweet Hunter:

- Create a month’s worth of content in an hour

- Amplify your reach and engagement rate

- Identify new leads automatically

Join 3,000+ creators, founders, and consultants using Tweet Hunter to grow their businesses.

Try it free for a full week + enjoy a 30-day money-back guarantee.

Linus introduces himself

I'm an independent researcher focusing on building better interfaces for humans to interact with generative models. In particular, I’m interested in interfaces that allow for direct manipulation of text using latent space based language models. Basically, what that means is that I’m interested in exploring ways to use language models that look less like using prompts and more like familiar user interfaces like pinch-to-zoom or drag-and-drop.

Before becoming a researcher, I was your average React-TypeScript-wielding product engineer. But I always had a side hobby and interest in building knowledge tools to help people learn and read quickly and things like that. At the start of this year, I decided to take a year off from work to dive deeper into that question.

I spent the first half of the year looking at classic natural language processing (NLP) approaches to that question. Since May or June, I've been looking at more language model-based approaches.

How he does his research

I research generative AI, but I also use a lot of generative AI tools in my workflow. Some of those tools are ones I’ve built myself—I have an array of personal micro-tools that support what I do. I also use a few publicly available AI tools. The ones I want to share today break down into two big categories: tools for reading, and tools for personal knowledge management—like notes and search.

We’ll start with tools for reading.

Tools for reading

To find papers to read I use Elicit

A big part of research is figuring out what to read. It’s important to be able to do literature reviews and find papers that are relevant to the question you’re interested in.

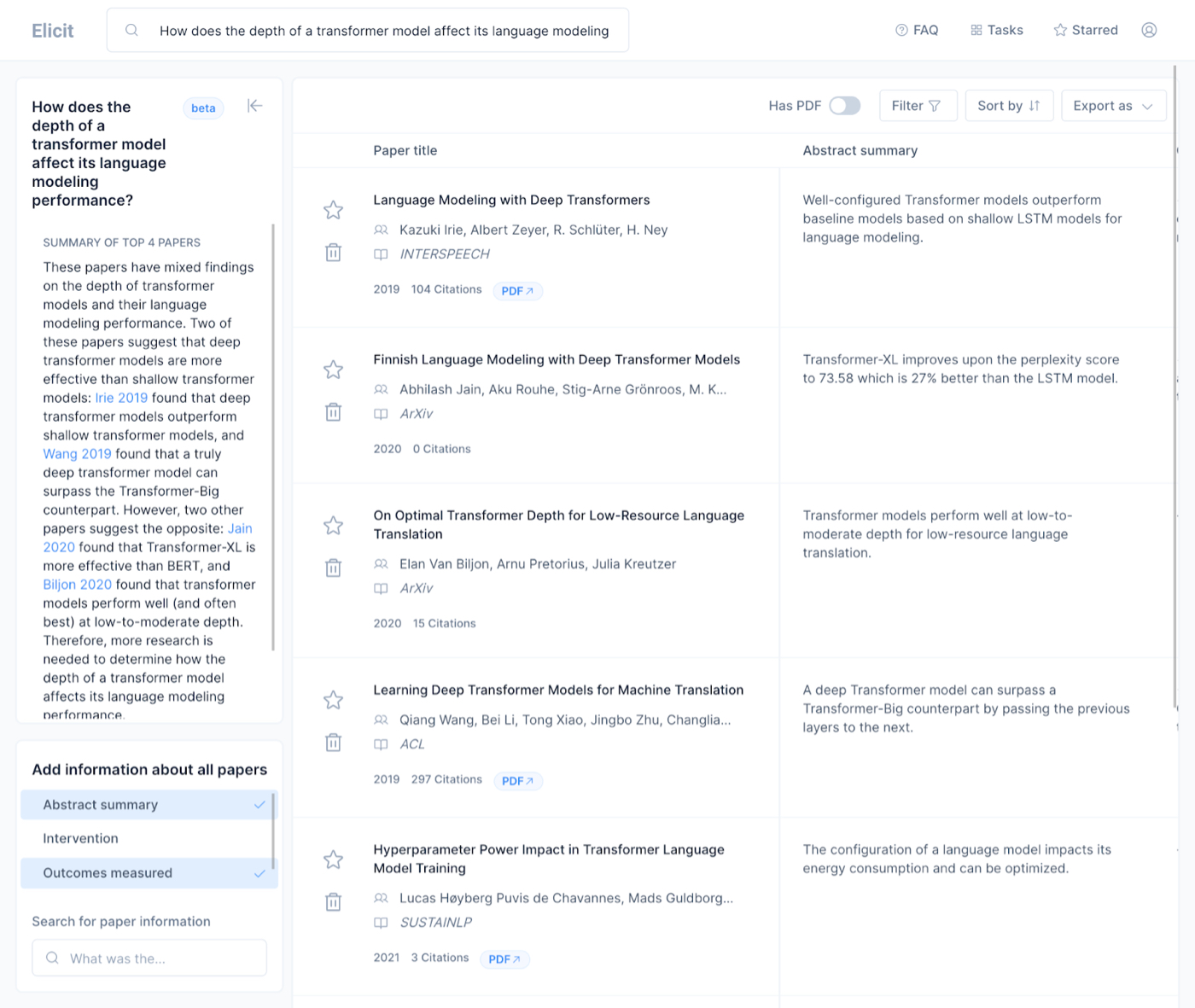

Elicit is a literature review tool that uses language models to aid in people searching for what to read to answer a question. I might have a question like, “How does the depth of a transformer model affect its language modeling performance?” This is a fairly technical question, but it’s basically asking, “How does one part of the model’s structure affect its performance?”

Normally if I had this question I would Google something like, “language model depth paper.” Then I have to look at each link to figure out: does this answer the question? Who is it by? Is it a reputable paper? What are the results?

It’s a time-intensive process. But Elicit changes that. If I ask a question in Elicit, it churns on it for a little bit and then outputs a list of relevant papers:

(A screenshot of Elicit)

The papers it finds are great. it also outputs a summary of the abstract, so I can quickly tell if the paper is going to answer the question that I have. It has filters for things like the number of participants in the study or what the intervention was in the study, which is relevant for social science papers.

This is a good way to just discover new papers, especially because there are paper links that you see on Twitter, but they're so biased towards the last couple of months, and this gets you historical papers that you might have missed.

ExplainPaper helps me understand dense papers

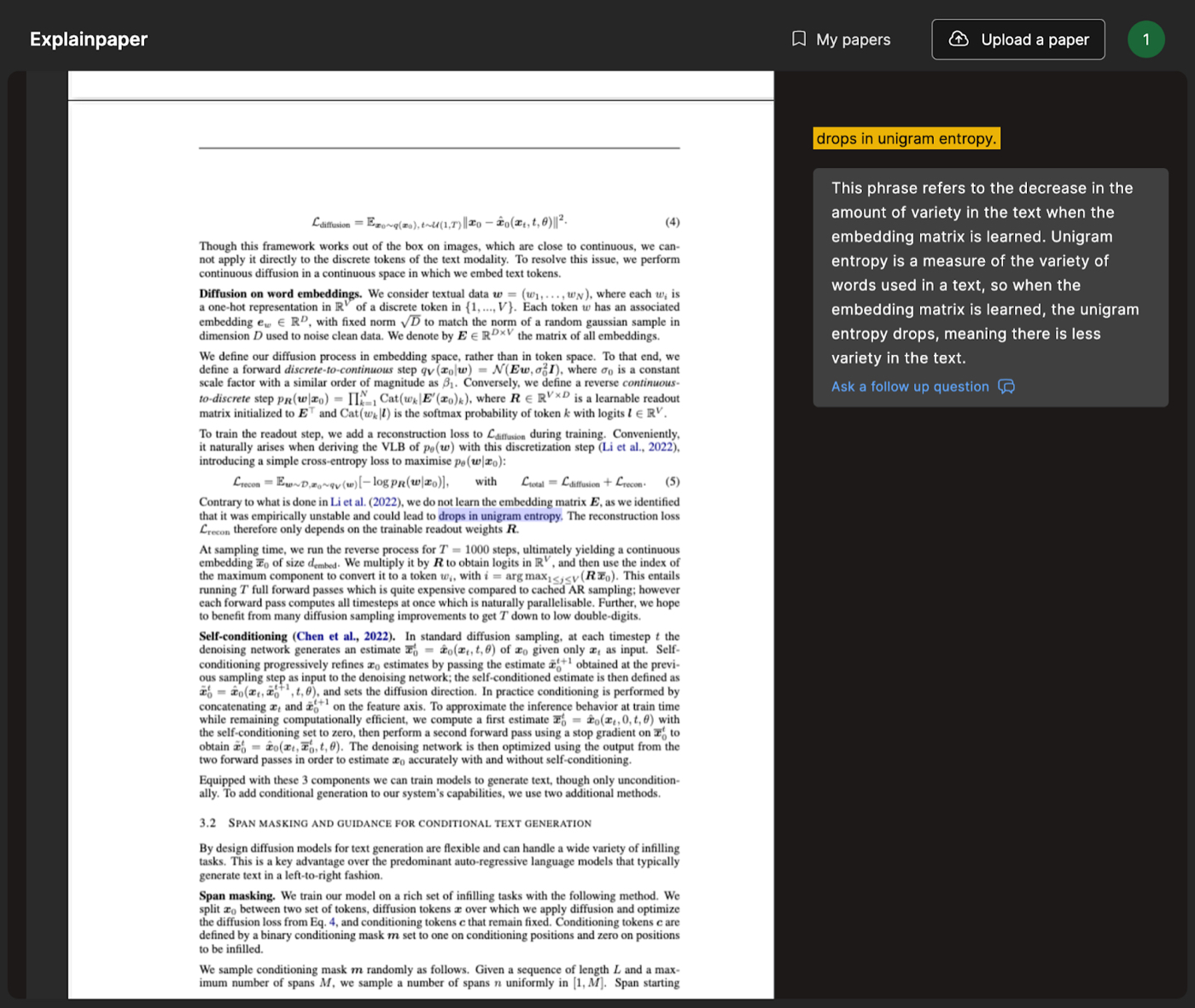

A new tool I’ve been using to help me read papers is called ExplainPaper. If you put in a paper, you can highlight any section of that paper and the tool will explain it to you.

This is useful for me because I don't come from a machine learning background, but I spend a lot of time reading papers to do the research I’m interested in.

Sometimes there are papers that are clearly written by engineers and other papers are clearly written by mathematicians. The ones that are written by mathematicians are just hard to wrap your mind around if you don't come from that world because they're a little bit too dense.

In ExplainPaper I can highlight a sentence that talks about an equation or a rule, and it will summarize and explain something that might be unclear:

(A screenshot of ExplainPaper)

I built a visual summarization tool for scanning through articles quickly

I read a lot, and sometimes I want to be able to get the most important parts of an article without having to read the whole thing. The obvious solution to this is a summarizer—but summaries have lots of limitations.

A summary is taking one wall of text and trying to get into a smaller wall of text. But you still have to scan through the summary. If you want to expand a specific point in the summary, you have to go back to the original text.

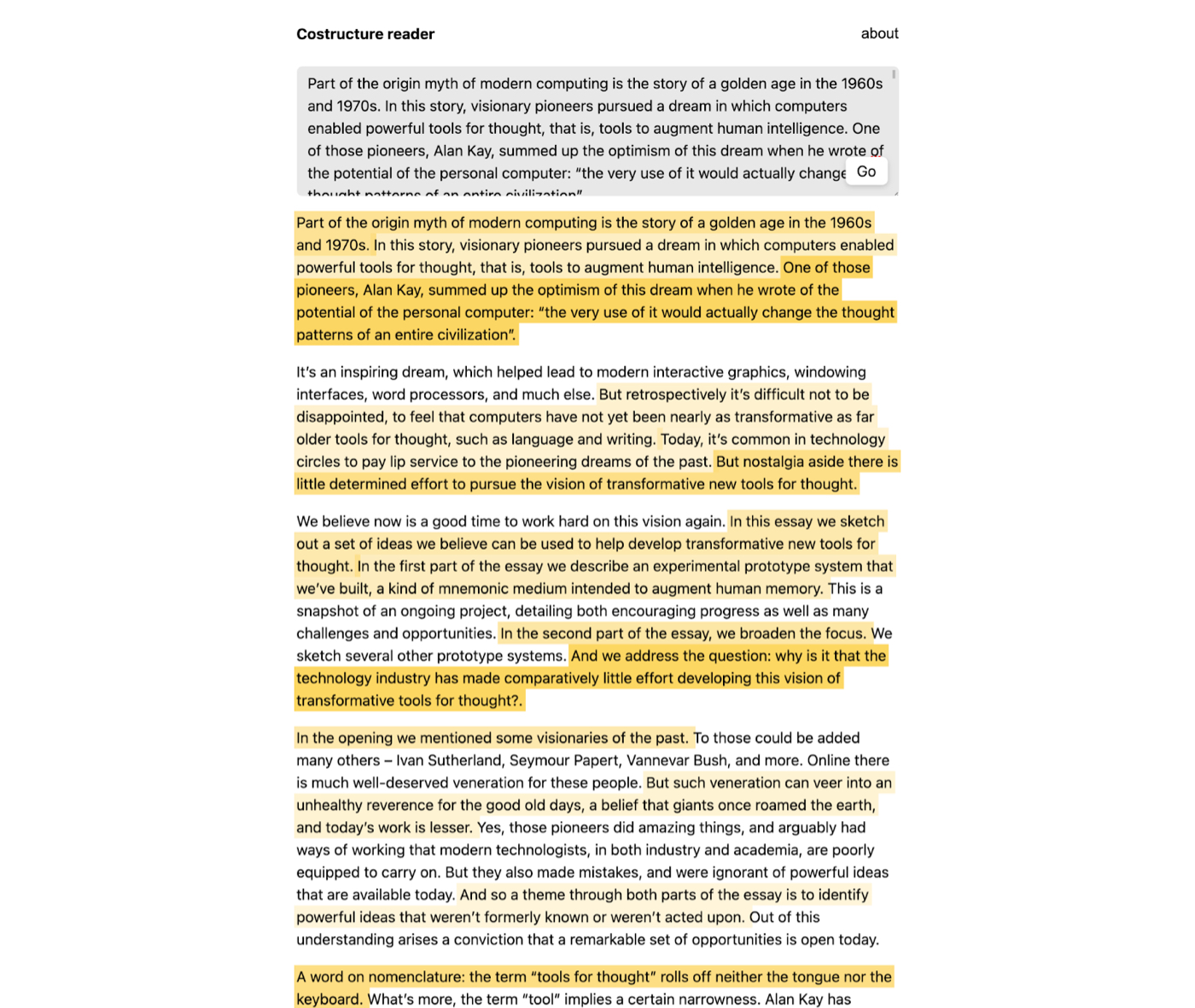

So, instead, I built a tool called CoStructure. It creates a visual heat map on top of an article to show me the most important sentences. So I can quickly jump to what’s most important without having to read the whole article.

I create the heatmaps with what’s called extractive summarization, which tries to identify sentences in the text that are most representative of the text as a whole by ranking every sentence in a text according to how many other sentences are similar to it. So if one sentence contains lots of topics that many other sentences mention, it ranks higher and is probably more central to the topic of the post.

Let’s say I’m reading an article and want to be able to skim through the most important points. I paste it into CoStructure like this:

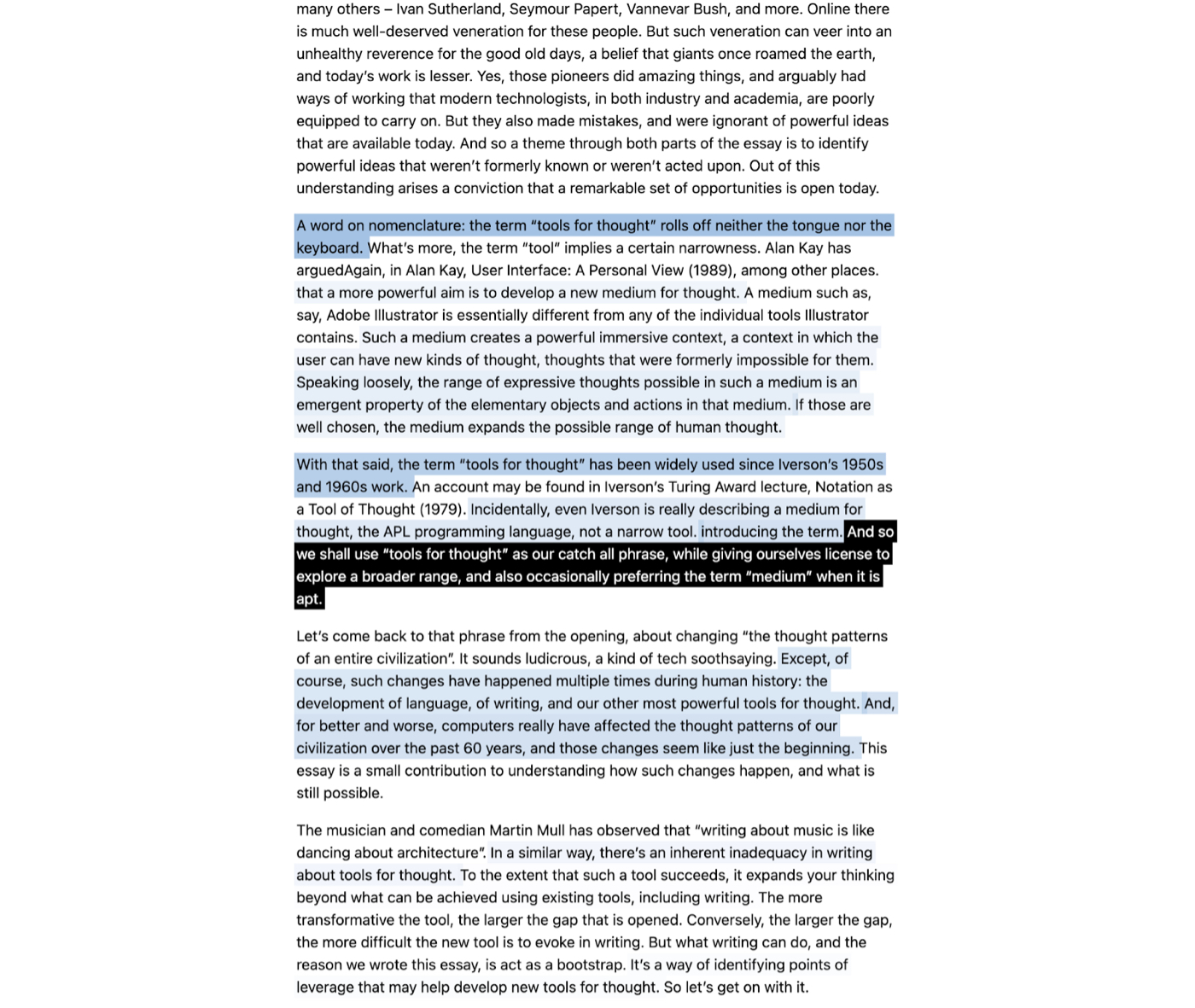

(A screenshot of CoStructure)CoStructure will highlight the most important sentences of the article for me in yellow, so that it’s easy to scan. If I'm interested in one part, I can click on that sentence and see what other sentences are most related to it:

(A screenshot of CoStructure)

It's a different way of exploring a text from the top down instead of from the start to the end.

Text is the most ubiquitous and the least user-friendly interface to information that we have. We have plots, we have graphs, we have tables. All of these are great. They are optimized for various different kinds of things for different uses.

Text is not optimized for anything at all. It's just a thing that we inherited from 3,000 years ago, and we haven't really improved it in any really interesting ways with technology. So the idea behind this was what if you treat text seriously as a medium for data visualization, and you try to take the understanding of text that computers can have now and overlay it on top of text to make it a more effective data visualization or data graphic.

Personal knowledge management tools

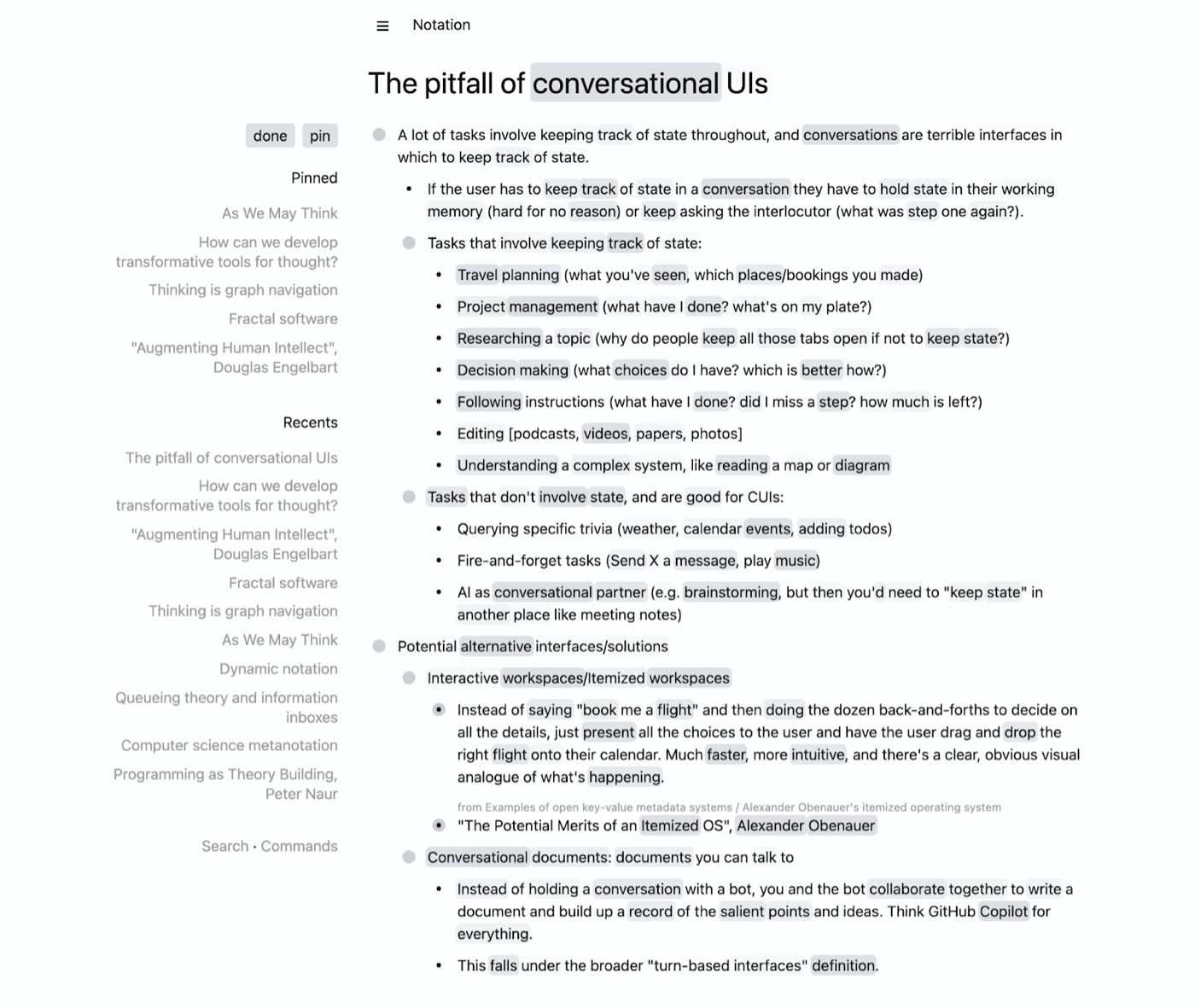

I take notes in a custom app called Notation

Another tool of my own creation is a notes app I call Notation. It’s my daily driver notes app right now, and it’s an outliner tool like Roam or Logseq. It’s a pretty typical outliner app, except it also has a machine learning angle to it.

If I open a note, you’ll see words are highlighted, and some are highlighted more darkly than others:

(A screenshot of Notation)

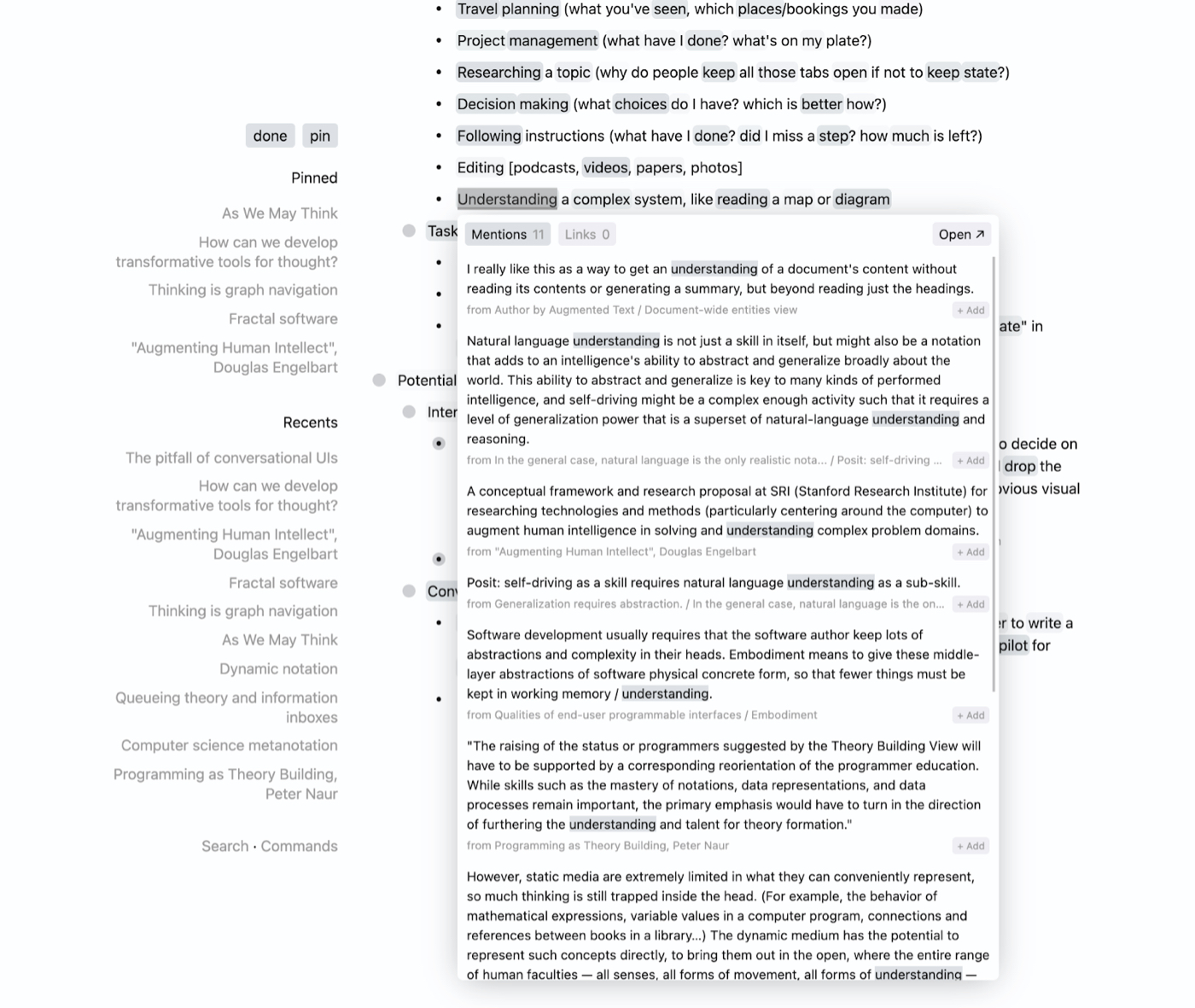

If I click a highlight, it will show me all of the other times I’ve mentioned this idea sorted by relevance:

(A screenshot of Notation)

The highlighting happens automatically by looking for other places in my notes archive where that word also appears. If it appears frequently, and if those other notes are closely related to my current note, the highlight gets bolder.

I built this as a response to the idea that no one should have to double-bracket every note that they take. (Editor’s note: see “The Fall of Roam” for more about double-bracketing notes.) I wanted to know what would happen if I built an app where you couldn’t double-bracket, and instead you had to rely on the model to do it.

My conclusion is that there are definitely corner cases where it’s useful to double-bracket, but for 90% of the cases, it’s possible to do it automatically by detecting semantic similarity.

I built two personal search engines to help me find all of my data

I have two search engines, Monocle and Revery. They search over an index of all of my data—journal entries, notes, contacts, tweets, bookmarks, and more.

Monocle is a full text search engine, which makes it useful for finding proper nouns and specific keywords. For example, if I want to know, “Have I met this person?” I can search their name in it. Here’s what happens if I search Taylor Swift:

(A screenshot of Monocle)

This type of search is also useful for personal trivia like airline rewards account numbers, discount codes, and restaurants with public restrooms.

Revery does semantic search—search based on similar meaning—which is more useful for finding out what I know about a topic. I use it as a Chrome extension: if I click a button, it will pull up results in a sidebar with related notes or websites I’ve seen:

(A screenshot of Revery)

A research example

The output of all of the tools I use in my workflow is the research results I generate. I’ll show you a few demos.

To grok these demos, it’s useful to have a working definition of what I mean by “latent spaces” and “latent space language models.” You can think of a latent space as a way to map the space of every possible sentence that a model could write. In a latent space, similar sentences are "close" to one another. These models are quite good at finding, based on an input, the parts of the latent space of all possible sentences that the output is likely to live in.

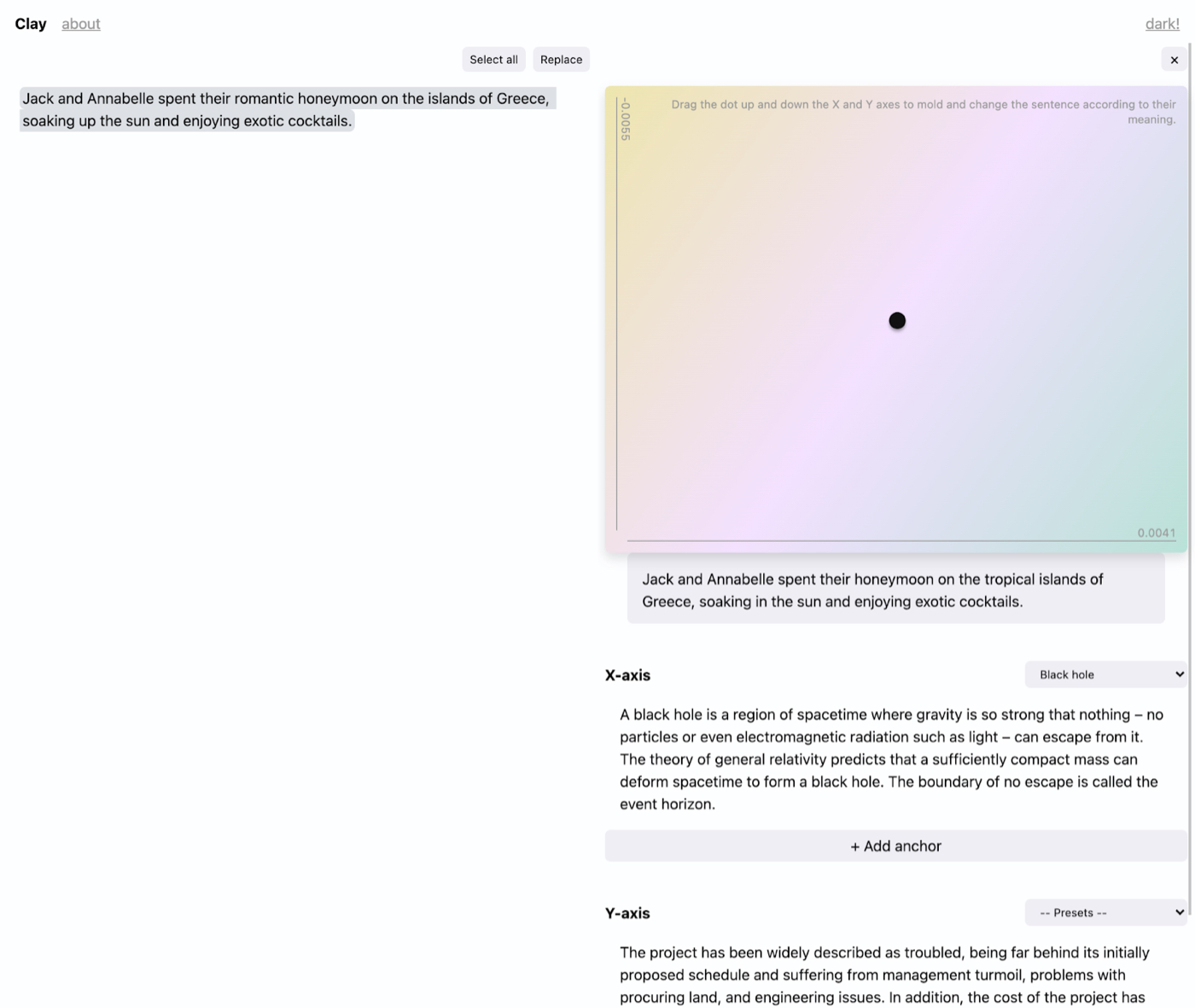

The question I was interested in answering with this demo is: can you build a language model with a UI that lets you move around in the latent space? And where movement in certain directions can make meaningful changes to the text?

(A screenshot of Clay)

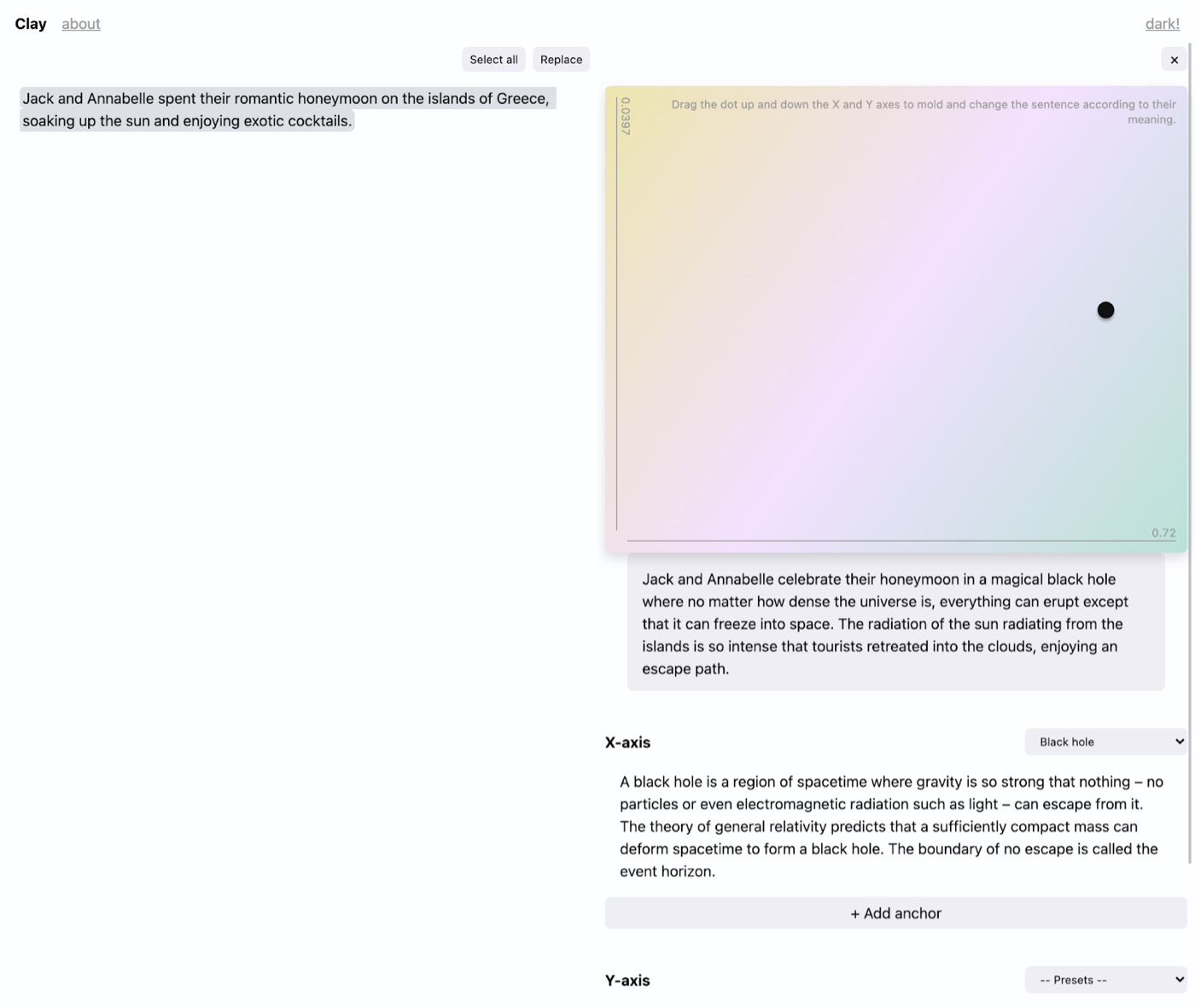

In this demo we have an example sentence about a couple going on a honeymoon to Greece. Then we get this rainbow colored pad (see screenshot) on the right with an X axis and a Y axis. Each axis represents another sentence—maybe the X axis is a sentence about black holes, and the Y axis is a sentence about a financial crisis.

If I drag this little dot around in space, it will modify the original sentence to be more or less about black holes. Or more or less about financial crises. The further I drag the further it goes:

(A screenshot of Clay)

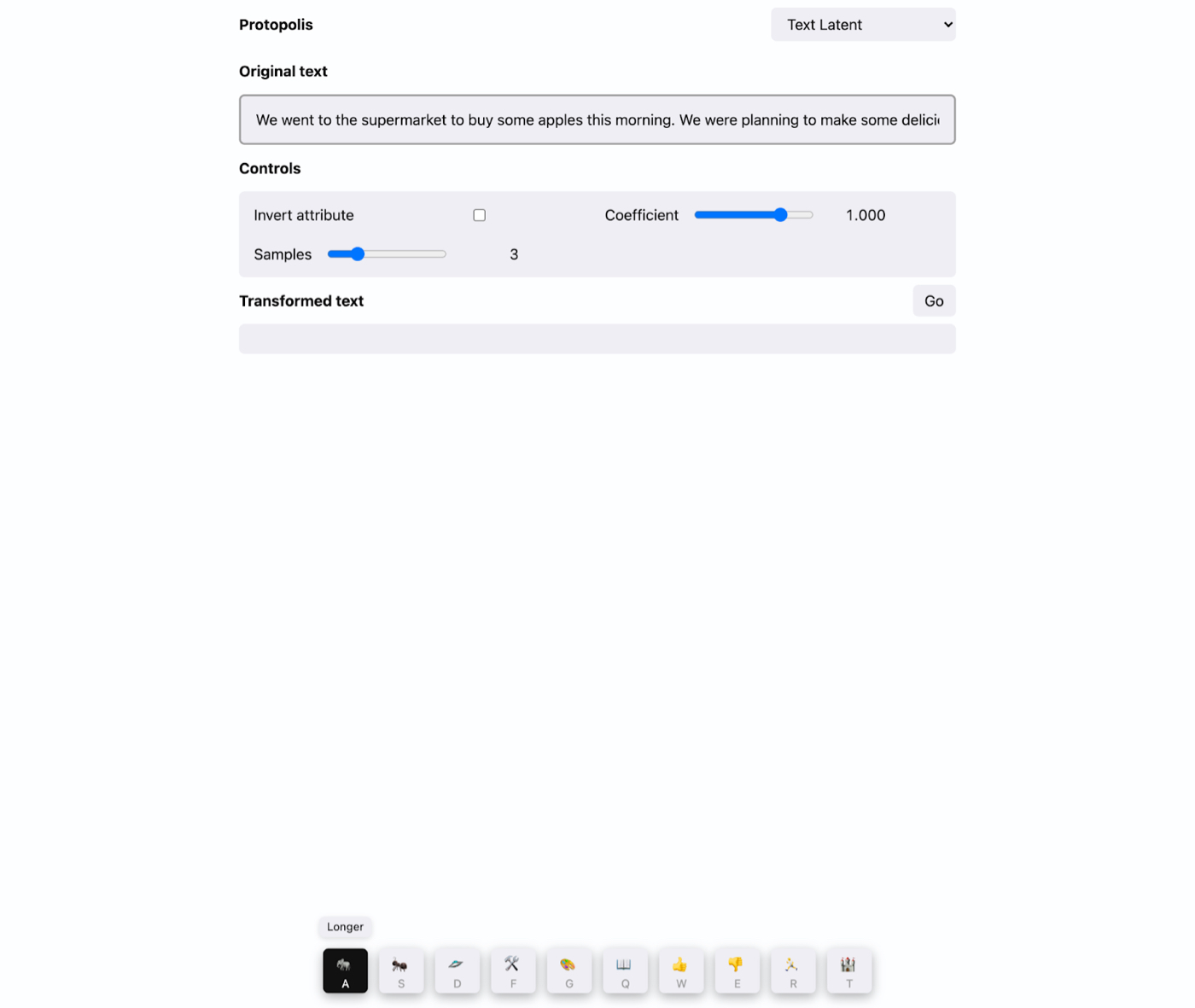

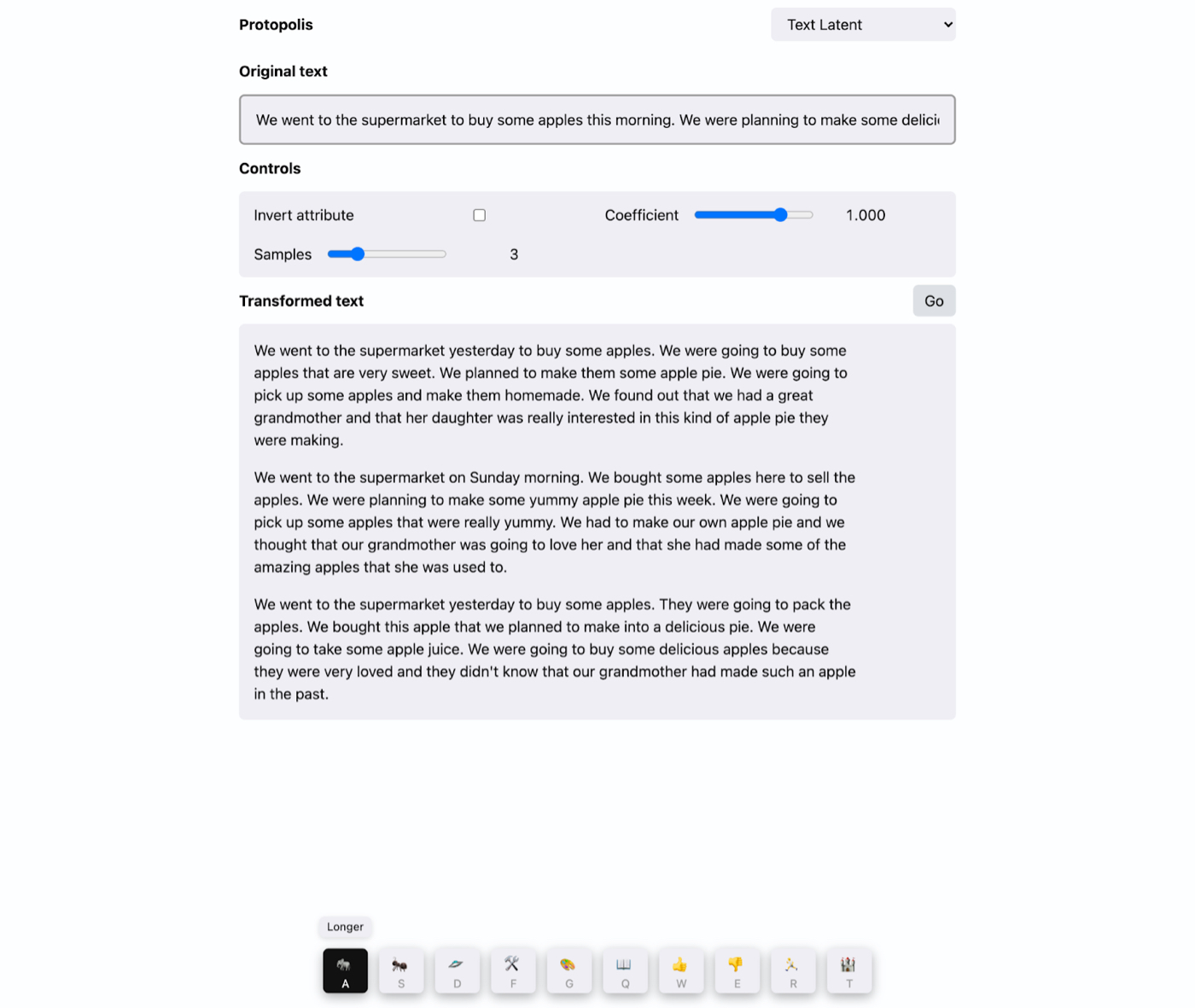

Another example demo is called Protopolis. Again, it starts with a sentence:

(A screenshot of Protopolis)

In this example, I have two sentences, “We went to the supermarket to buy some apples this morning. We were planning to make some delicious apple pie later.”

I can choose an attribute direction, like “length.”

(A screenshot of Protopolis)

As I change the coefficient, it will make the text longer while preserving the original meaning.

I think these kinds of interfaces are going to be extremely important for AI to get more general adoption. Prompting models are still a kind of dark art, and for generative models to live up to their potential, humans are going to need much more precise and predictable control over their output. These interfaces are a glimpse into a future where we'll be able to control outputs from these models more directly and more precisely. It'll enable interactions like "pinch in to summarize this text," or rotating a dial to specify exactly how formal or blunt you want to sound in your email. I'm excited about this research direction because it opens up new ways of manipulating text directly in "meaning space" rather than just by typing paragraphs word-by-word into a text box.

Book recommendations

Diaspora by Greg Egan and Exhalation by Ted Chiang are the two books that have influenced me most deeply that I recommend to friends over and over again. They’ve changed the way I imagine the future of humans and technology and, by extension, deeply impacted the work I do with AI and text interfaces.

Diaspora is a science fiction novel about a far-off future where humanity spans our solar system, diverging into a myriad of genetically mutated biological forms and computer-enabled virtualized forms in the process. But the book isn’t really about space exploration or the manifest destiny of civilization. It follows a protagonist’s pursuit of the basic, eternal questions: What does it mean to be human? What is knowledge? Is there something beyond this universe? In the process, the novel blitzes through a tour de force of some of the most interesting ideas about future technologies, literacy and language, and living in simulation that I’ve ever come across, many of which directly inspire my work.

Exhalation is a collection of short stories by the writer Ted Chiang, whom you might know better as the author of the story that inspired the film Arrival. My best endorsement for this work is that it single-handedly convinced me, a devout writer of blogs and nonfiction essays, to try my hand at writing short science fiction stories myself. His stories are nominally about science and technology but take place in such fantastical alternate timelines that reading them often lets me peer back into our current reality through new lenses, as an observer from another world.

Do you build an AI tool or do AI research? Do you use AI to do your work?

If yes, I'd love to interview you for a future Superorganizers edition. Just hit reply to reach me!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Hi Dan - very interesting article. Are the tools that you mention which are not hyperlinked available publicly? The Revery tool peeked my interest in particular. Thanks for the post!