Imagine that your belief system became a laughing stock. Twitter grifters made threads about you. Analysts made a name for themselves critiquing your ideas. Politicians used your projects as a punch line. Every day was an exercise in self-doubt, questioning, and suffering.

Most people might decide it was time to take either a nice holiday or a quiet retirement.

This is what happened to Chris Dixon, crypto’s prophet. To his credit, he did not go quietly into the night. Instead, he decided it was time to write a book.

If you are unfamiliar with Dixon, he is the most successful crypto venture capitalist in the world. The man has printed fat stacks of cash for his backers, turning his first $350 million crypto fund into roughly $6 billion. In 2022, when he topped Forbes’s ranking of VCs, his boss at Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), Ben Horowitz, predicted that he would be the "best investor of his generation." The company’s crypto unit, led by Dixon, raised $515 million in 2020, $2.2 billion in 2021, and $4.5 billion in 2022.

On a personal level, I respect his writing and intellectual rigor. His blog was formative for me early in my career; the succinct prose he used to publish on a regular basis made me a better analyst.

All of which is to say that this dude has the juice. He is worth taking seriously.

In a move I admire, Dixon decided to publicly double down on crypto with his new book, Read Write Own: Building the Next Era of the Internet. If there were ever a book and an author by which to cast judgment on the technology’s worth, this would be the one. I have written about crypto, but I’ve never felt comfortable casting an ultimate value judgment. With this book, it was time.

Dixon argues that many of the internet’s problems come down to technical architecture. Because corporations control networks of people and the internet infrastructure they use to connect, corporations accumulate too much power. His thesis is that because blockchains can decentralize some aspects of that architecture, obviating those corporate power centers, the internet will be better for everyone involved.

I would consider myself techno-optimistic. I strongly believe in the necessity of technology to improve our world and have dedicated my life to that belief. It would bring me nothing but the greatest pleasure to announce that crypto solves the internet’s current problems.

I regret to report that both the book’s arguments and crypto’s grand promises fall short of that mark. Yes, corporations are too powerful, and yes, technical architecture is part of the reason why. However, the problems that emerged during the era of crypto scams and scandal in the early 2020s are similarly derived from the blockchain’s technical architecture—just like corporations.

Use cases that almost wholly differentiate on the blockchain’s technical edge, like sending money internationally, make sense, but my belief is that crypto will fall short of Dixon’s lofty ambition for it. His arguments are well reasoned but underweigh several key variables around human psychology and the nature of competition online.

The heart of the issue

The original promise of the internet was to be a free, democratic exchange of ideals. Instead, we got digital monopolies, the collapse of local journalism, and Logan Paul. What happened?

Dixon thinks that corporations are to blame. He views the history of the internet in three distinct phases:

- Read: In the 1990s, anyone could go online and read stuff. The internet “democratized information.” It was the “golden period of innovation and creativity.”

- Read-write: Starting in the mid-2000s, we “democratized publishing. Anyone could write and publish to mass audiences on social networks and other services through posts.”

- Read-write-own: “The read-write-own era, now upon us, is democratizing ownership. Anyone can become a stakeholder in a digital service or network and so gain power, governance rights, and economic upside.” To translate: By using blockchain technology, regular consumers can receive crypto tokens that offer governance rights or economic upside in the services they use, hopefully incentivizing positive behavior.

Dixon’s beef is mostly with the “write” era. In his eyes, big, bad corporations changed everything. Zuckerberg and his ilk “wrenched control away” of cyberspace from the common man. To prove his case, he cites a litany of scary-sounding stats. “The top 1 percent of social networks account for 95 percent of social web traffic.” Or “the top 1 percent of search engines account for 97 percent of search traffic.” Perhaps worst of all, “startups and creative people increasingly depend on networks run by megacorporations like Meta…and Twitter…to find customers, build audiences, and connect with peers.”

I have multiple quibbles with this characterization. A cheap shot I can’t resist making: a16z—Dixon’s employer—is now a major shareholder in Elon Musk’s version of Twitter, and a16z founder Marc Andreessen sits on the board of Meta. It feels funny to complain about the companies that are enriching the firm and man that pays you.

Chippy asides notwithstanding, yes, a select few top companies dominate the internet, but that is because, as I’ve been saying for years, the power law is the only law on the internet.

It is a rule of digital physics, immutable and undeniable. Most of the value always has and always will flow to the top 1 percent.

In 1998—which Dixon saw as the glorious “read” period free of corporate domination—Yahoo had 40 million monthly users when there were only 90 million people online. When Yahoo went public in 1996, there were only 100,000 websites—total. People almost exclusively found them through internet portals like Yahoo. The power law funneled all traffic into aggregators of attention.

Our day is no different, with big tech vacuuming up most traffic. But even on the more niche platforms, the power law still holds. On Twitch, 50 percent of revenue was made by the top 1 percent of streamers in 2021. On Patreon, 70 percent of revenue comes from 3 percent of Patreon accounts. In 2020, the top 10 percent of OnlyFans creators made 73 percent of revenue. The power law stays true regardless of whether the platform is big tech or not.

The reason the power law exists isn’t corporate greed; it is human nature.

And not to go all first-year-grad-student-at-Berkeley here, but the problem of the power law is inherent to the capitalist nature of the internet. Competition for limited eyeballs is the primary driver of the power law. People pay for what they consider the best. If all URLs are competitive, then of course cyberspace devolves into a winner-take-most dynamic for each job to be done for consumers.

The internet is bloody, brutal attention combat, and it doesn’t matter which tech company sits on the throne—the power law is the ultimate ruler. Despite our divergence on the root cause of power laws, however, Dixon and I do agree on how those power laws organize themselves: networks.

The internet has problems

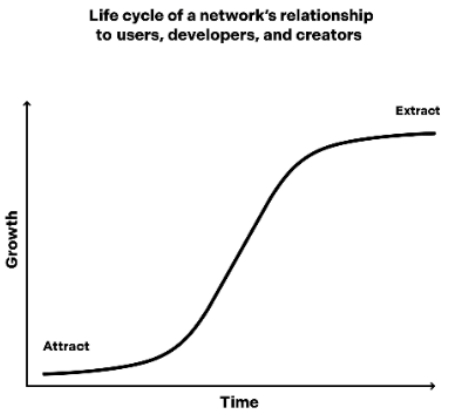

The power law has such gravity partly because of network effects: The more people that join a service, the more valuable it becomes. For many internet companies, these people are a combination of consumers, content creators, and developers. Jump-starting those networks is tougher than you can possibly imagine, but once the flywheel starts turning, each successive user finds more value from the network, and it will grow ever faster (in theory). Each network’s power dynamics are a little different in practice, but that is the general idea.

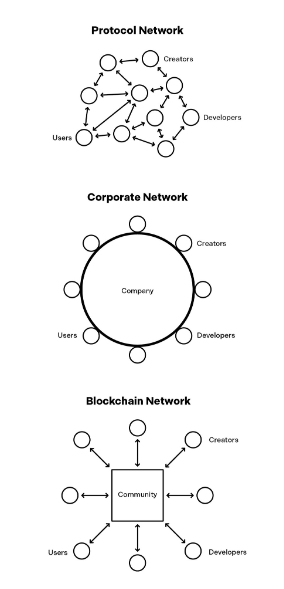

Dixon argues (and I agree with him) that there are three types of digital networks:

- Protocol networks are technical standards that anyone can use and are maintained by a loose federation of nonprofits and global organizations. Dixon has a wonderful definition for these that I’ll happily steal: “Think of protocols as analogous to natural languages, like English or Swahili. They enable computers to communicate with one another. If you change how you speak, there’s a risk other people won’t understand you.” Email is the easiest example of this phenomenon. No one owns it, and everyone builds on top of it.

- Corporate networks are the Facebooks of the world. These are almost always backed by venture capitalists and raise large amounts of money to subsidize users in the beginning. Companies sit in the middle of the network and have unilateral decision-making authority over the rules and operating mandate. All hardware and software is within their dominion.

- Blockchain networks have a decision-making body whose rules are written in immutable code on the blockchain. For the unfamiliar, you can think of a blockchain as a community-run, distributed computer—like a Google Sheet in which everyone can track changes. To gain access to this computer, you get tokens that give you a variety of rights, ranging from economic to governance. Sometimes you earn the tokens by performing tasks, sometimes they are given away by the founding team—it all depends on the project.

Source: Read Write Own.

What we are really talking about with network structures is coordination mechanisms. What is the best way to organize people and resources? How should those people be incentivized?

You can boil Dixon’s network framework incentives down to the following: Protocol networks want their service to stay up. Corporate networks want their company stock to go up. Blockchain networks want their crypto token price to go up. All of the wonder and all of the glory of the internet comes down to those three sentences.

Of course, each of these network methods has its respective downsides.

Protocol networks are a great idea that—according to Dixon—you can’t pull off anymore. The ones that are still successful, like email, were almost all started in the 1980s and ’90s, before any venture capitalists had figured out that you could get stupid rich by owning these networks. In Dixon’s mind, the protocols only ended up winning out because of a power vacuum on the internet. Protocols—like RSS, for my internet readers who remember the good old days of Google Reader—lose the feature battle to corporate networks: Protocols are hard to use and require a decent amount of technical knowledge. By comparison, you could open up a Twitter account with an email and three clicks. Corporate networks can out-build and out-fund protocol networks 99 times out of 100.

Corporate networks have the primary problem of being run by people in San Francisco. If you have opinions or actions that they don’t like, you can get booted off the platform. Because essentially all commerce and information runs through these platforms, there are dire consequences for said booted individual. That isn’t great! And it is a problem no matter your politics. Under Jack Dorsey, right-wingers were always whingeing. Now under Elon, the left is howling. No matter which billionaire asshole CEO you prefer, it still comes down to the fact that moderation of the world’s biggest platforms is run by billionaire assholes.

More troubling to me is the take rate that a platform puts on its users. In the beginning, when VC dollars flow like La Croix, platforms will subsidize users to get as big as possible. Eventually, though, they hit their local maxima in users or market and start extracting profits. However, because network effects have already decimated viable alternatives, users don’t have a choice but to pony up. Dixon calls this the attract/extract cycle.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Excellent post. Per your last paragraph, what do you think about blockchain as an infrastructure for an AI based economy, ie a ledger for AI to transact with AI.

@Mark_5418 i think it could work? Honestly, the devil is in the details—attribution, what blockchain, etc—that I don't think anyone has sorted out yet. The theory could be right? Vaguely similar to my feelings on crypto before writing this review. Good idea, details are iffy.

Loved this post! The arguments were very strong, nuanced, and well researched. They were written with great clarity in thought and simplicity in style. I enjoyed your writing style a lot and was taking notes — will be back for more

@sajjad585 Thank you! I appreciate that :)

So glad you decided to take this on and provide the benefit of your experience, wisdom, and well-calibrated bullshit sniffer. Your article proves again why Every in on my desktop. I don't have to care about crypto and I don't. I am curious. You write to the curious. You provide worldview information and being well-informed makes for rich and deep conversations. And better questions.

@Georgia@Communicators.com Thanks Georgia! appreciate that

Really good write-up! It's hard to read a book by him as anything other than looking to prop up his investments but I think you approached it very fairly.

I'm failing to find the clip but there was one with Chamath and some other crypto investors basically describing how they would fund tokens and then exit early at the peak. It was so damning of the entire VC industries treatment of crypto as purely a speculative investment vehicle while they try to say otherwise.

I say all this as someone who was amazed by Ethereum and its promises for computing years ago. I still find it all technically very impressive, but I am not convinced it really offers enough to go spend my time trying to build with it.

Found it - https://twitter.com/SilvermanJacob/status/1595059806200643589

Well balanced article. Agree on risks of hard coded “laws “ - we know the problems this causes with literal religious zealots. Also the need for an effective organizational architecture to have both carrot (incentives) and stick (punishment).I am excited by the transparency blockchain record keeping brings, plus the joyful self adaptation of these huge open-sourced systems

What a rollicking great read!

‘ If everyone’s in charge, nobody is.’

I'm thinking chaos & Blockchain & patterns like a roller coaster with no track.

Driven largely by emotion and fantasy.

Blockchain is pushing change which is a good thing.

Almost bought the book but now I don't feel that's necessary given this clear summary and incisive analysis. My Every subscription is paying for itself! Pls keep it up

"I may be a little bit nit-picky with these examples" No, the specificity and attention to detail is what makes this article great. I think Dixon is someone who got in early, made a lot of money, and now he is "the guy" to go to about crypto. He succeeded in this space, he is still making his living off of it, winning is great, but failing teaches. He hasn't failed, his job is secure, he is managing billions of dollars, so he holds firm to the ideas that ignited his passion for the space in the first place. He is to crypto what Ninja is to streaming: the man who got in at the right time, became the face of the movement/ idea, and made the most money/ had the most success that anyone ever will. More than anything, I just have to believe that anyone who is so sure in such extreme, "all-in" views is wrong in some way, because everything is nuanced, there is no magic wand to wave that will make everything perfect.

Hello:

I just listened to an interesting podcast with Mr Dixon on the a16z network and he stated that he would like to respond to comments, pro or con. I think it would be interesting to learn from the two of you chatting???