A couple weeks ago, Wish.com filed their Form S-1 with the SEC (under their corporate name ContextLogic). Wish has raised over $1.6 billion and was last valued at $11.2 billion in August 2019. The IPO should be a jolly moment, right? Maybe not.

The future doesn’t look great. Wish has rising customer acquisition costs. Their gross profitability is falling because a government subsidy on shipping is disappearing. It’s also not totally clear that a lot of people actually like their product.

It’s like Wish is running a government-subsidized non-profit dedicated to the noble cause of learning the most effective growth hacks on Facebook Ads. Instead of trading their stock, I might suggest reaching out to members of their marketing team and paying them lots of money to come work for you.

This isn’t actual investment (or hiring) advice, do your own research please don’t sue me thanks.

Alright, enough with the jokes and onto the analysis.

What is Wish?

Wish was founded in 2010 as a mobile-first discount commerce app. It works like this: first, a customer downloads the app (90%+ of user activity and purchases happen on mobile). Then, they scroll through photos of items. Wish sells everything from Bluetooth headphones to baking sheets to swimsuits. Most of the prices are 80 to 90 percent off of their original price, so it seems like you're getting a steep discount.

The key to their model is that customers trade price for convenience. When you place an order on Wish, it takes two to four weeks to arrive. On the backend, Wish places the order with manufacturers in Asia for a steep discount and sends it to you. While many discount retailers have to hold inventory in the U.S. (near their customers), without that cost, Wish can offer the lowest prices.

In slight contrast to Amazon, which competes on both price and convenience, Wish focuses exclusively on price. It turns out that there are many shoppers that value price over everything else, described by CEO Peter Szulczewski in a blog post from 2016 as “The Invisible Half”.

Especially early on, they leveraged Facebook and Instagram ads for growth. They became notorious for their… strange advertisements.

Most people who discovered the app in its early years did so through Facebook and Instagram, where it still regularly ranks among the platforms’ top advertisers. There, amid endless hyper-targeted campaigns, its ads have become notorious for their occasional weirdness, thanks to an algorithm that pulls in some of the most confounding products from Wish’s catalog of 200 million items: adult diapers with an attached rubber hose (?), shapewear ... for your face (??), and a $2 pile of what appears to be worms (???). There are no product labels on most of these ads, so you have to click over to Wish.com — or download the app on mobile — to find out what you’re looking at. (Source).

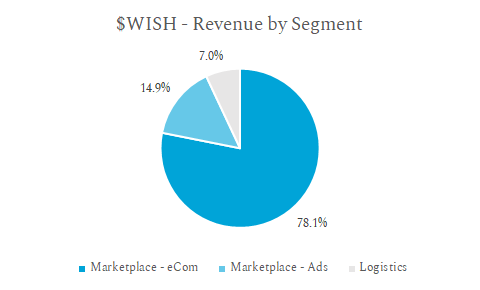

Wish earns most of their revenue from “marketplace services”, which includes their core eCommerce product as well as a native advertising product called ProductBoost. Marketplace services represent 93% of their revenue in 2019, of which 84% of that (78.1% of total) was their core marketplace revenue. The remaining 7% of revenue was from logistics services (delivering goods from merchants to customers).

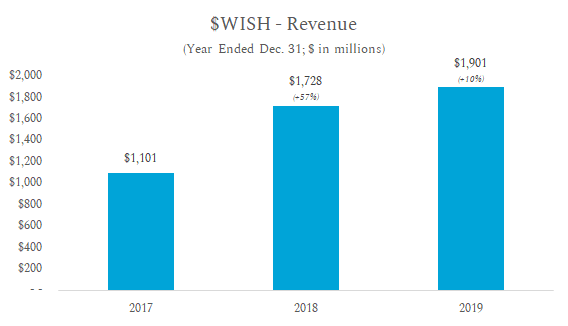

They ended fiscal year 2019 with $1.9 billion in revenue, up from $1.7 billion in 2018 (10% YoY growth) and $1.1 billion in 2017 (57% YoY growth).

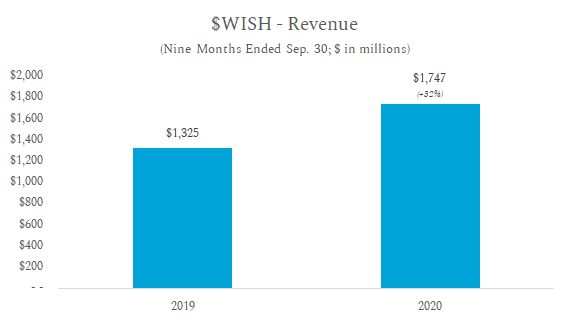

The nine months ended September 30 they had revenue of $1.7 billion, up 32% from $1.3 billion in the same period last year.

Shipping Rates & The Universal Postal Union

It’s not uncommon for value retailers to have a high-volume, low-margin model. Amazon has maintained a negative (or small positive) margin on its retail business for years and CostCo famously only makes margin on its memberships. This is no different with Wish, but with a big caveat: the model’s efficacy is predicated on a discount shipping policy by the Universal Postal Union Treaty. But the future of this law is murky.

For those unfamiliar with the Universal Postal Union (cough not me cough cough), they are a “specialized agency of the United Nations that aims to organize and improve postal service throughout the world and to ensure international collaboration in this area” (source). They were founded in 1874 to facilitate international trade. While some of the principles created by the UPU are obvious (uniformity of units of weight, for example), it also created discounted shipping rates for parcels to and from developing countries.

The goal was to help developing nations participate in trade to participate in the global economy and increase their quality of life. As part of the program, richer countries like the U.S. agreed to subsidize exports moving from companies in poorer countries to companies or consumers in richer countries.

These subsidies applied to parcels moving from China to the U.S. and many companies took advantage of this.

However, now that China is a much larger country, the Trump Administration decided that they didn’t want them to have discounted rates. So in October 2018, President Trump announced that the U.S. would exit the UPU in a year if the “group’s 192 members did not agree to reform the rates that countries charge each other when delivering mail and small packages across borders” (source). One industry executive even described the situation as “Trump having his own Brexit.” Luckily a new deal was signed in September 2019 with the stipulation that the U.S. would get to set its own postal rates starting in July 2020.

Just as planned, on July 1, 2020 the international shipping rate changed. Originally designed for mail, the UPU only regulates packages under 4.4 pounds. In the past, the cost to ship a 4.4-pound package from China to the U.S. topped out at $5.41 — less than it would cost a U.S. seller to ship the same item to a U.S. address. Now, under the current rate of $2.87 per package + $3.95 per kilogram (~2.2 lbs), that same 4.4-pound package will cost $10.77 — almost double.

And thus, we return to Wish. If shipping rates on cheap goods from China are rising, and a lot of the items on Wish are cheap goods from China… well, you can see the issue. From page 27:

Historically, our merchants in China have benefitted from lower shipping costs due to the Universal Postal Union Treaty (“UPU”). Certain expected changes to UPU postal rates that went into effect in July 2020 are likely to increase the shipping rates our merchants incur to ship products from China. The actions we have taken in our logistics program to mitigate these increased costs may not be successful over the long term. [Emphasis mine]

Regardless of if this exact policy remains intact, or if you believe in the policy, there’s no way out of this risk for Wish. They are trying to source from other countries (including the U.S. through their Wish Local program) but most goods still are prohibitively expensive to manufacture here because of higher labor costs. Their model is built on offering the cheapest goods. One could also say it was built on an international trade subsidy that’s disappearing.

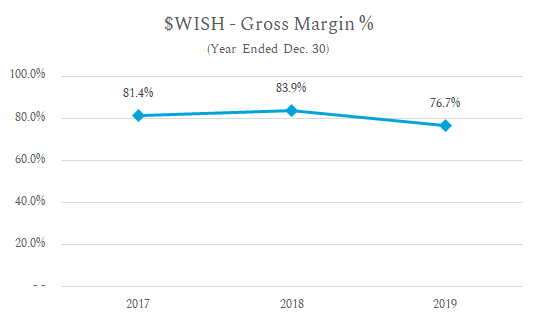

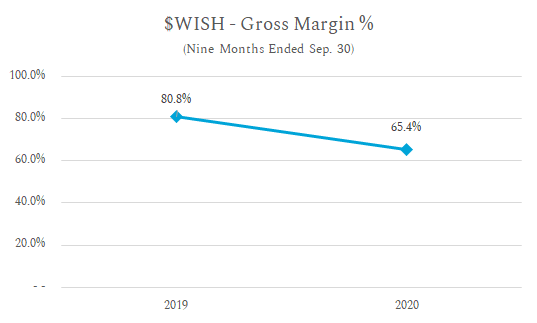

Looking at their gross margins confirms this reality. While their gross margins from 2017 to 2019 were pretty flat…

...during the nine months ended September 30, 2020 Wish saw a ~15% decrease in gross margin.

Remember, the subsidized changed July 2020. This is what’s included in their Cost of Revenue:

Cost of revenue includes colocation and data center charges, interchange and other fees for credit card processing services, fraud and chargeback prevention service charges, costs of refunds and chargebacks made to our users that we are not able to collect from our merchants, depreciation and amortization of property and equipment, shipping charges, tracking costs, warehouse fees, and employee-related costs, including salaries, benefits, and stock-based compensation expense for our infrastructure, merchant support, and logistics personnel.

It’s likely that these shipping charges were the biggest change over the past year. Either way it’s a serious risk to the business.

Rising Acquisition Costs

Would you feel comfortable investing in a business that likely requires over 3 years of customer retention to pay back its acquisition costs? Especially when you are selling commodity goods to discount buyers and feeling pressure because you lost government subsidies?

One of the most concerning things about Wish is their increasing customer acquisition cost (CAC). CAC is defined as the cost to acquire a new customer. If a company spends $100 to acquire 5 customers, their CAC is $20.

However, there’s a bit of nuance here. Some companies (like Wish…) spend money on Sales & Marketing (S&M) but their active customers decrease. This is because a portion of the existing customers churn.

So, just because a company increases the number of customers by 5 doesn’t mean they ended up with 5 more customers than they had before. Often, there’s churn. So maybe the company had 50 customers in the first period, they spent $100 on S&M, and ended with 55 customers in the second period. But instead of having 0 churn and 5 new customers, it’s more likely that perhaps 3 customers churned and they acquired 8 new customers. The true CAC in this scenario would be $100 / 8 = $12.50 instead of $100 / 5 = $20.

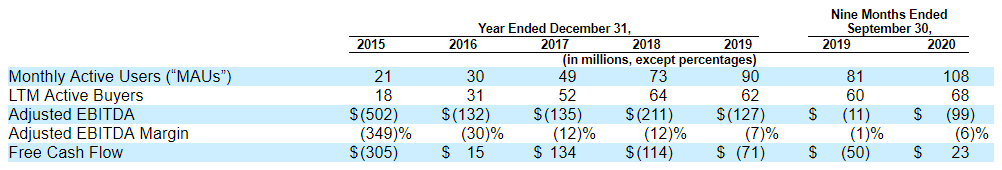

With that stipulation out of the way, let’s look at Wish’s numbers. On page 19, Wish provides a table of select five-year financial data.

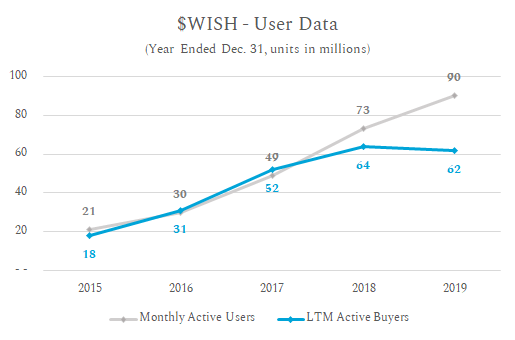

Even more interesting is the user data in graph form. This is the first sign of concern: while their users continue to rise, the number of people buying things has plateaued.

Let’s dive a bit deeper. On page 91 of the S-1, we get information about their customer LTV.

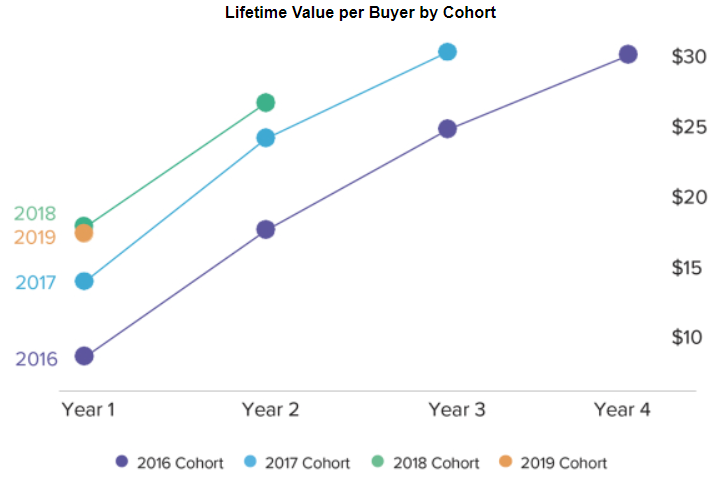

So by year 4, Wish has collected a cumulative $30 in gross profit for each 2016 cohort buyer. The good news from this graph is that each cohort is improving. In 2017, for example, the LTV of a buyer exceeded $30 by year 3 instead of year 4. However, the bad news is that an LTV of ~$30 isn’t very much, especially when we consider the cost to acquire customers.

Note that Wish calls their customers “buyers” and they will use terms like “BAC” (buyer acquisition cost) in their filings. I’ll interchange BAC and CAC in this analysis.

Wish doesn’t give exact BAC numbers, but we can make good estimates based on information they provide. We are doing this because it turns out that their acquisitions costs have likely been increasing. From page 91:

All of our annual cohorts since 2016 have achieved a BAC payback period of under two years, and our most mature of the cohorts disclosed – the 2016 cohort – has achieved a 2.8x LTV to BAC ratio by year 4. We are intently focused on managing our BAC and are using our data science capabilities to implement more efficient buyer acquisition strategies as we scale and target additional users and buyers in new geographies.

It mentions the 2016 cohort “has achieved a 2.8x LTV to BAC ratio by year 4”. By Year 4, the 2016 cohort had $30 of LTV. If the LTV to BAC was 2.8x, that means their BAC for 2016 was about $10.71.

The S-1 also mentions that “all of our annual cohorts since 2016 have achieved a BAC payback period of under two years”. We can estimate the BAC for these years to be between the Year 1 LTV and the year 2 LTV (after all, if the payback was under one year instead of two years, they would’ve said that).

So, to summarize Wish’s BAC over time:

- 2016: ~$10.71

- 2017: Between ~$15 and ~$25

- 2018: Between ~$19 and ~$27

What about 2019? This is murkier. I couldn’t find any direct information, but there’s perhaps a telling sign.

In 2018, Wish spent $1.576 billion on marketing and increased their LTV Active Buyers from 52 million to 64 million.

In 2019, Wish spent $1.463 billion on marketing and decreased their LTV Active Buyers from 64 million to 62 million. So while we won’t get to a perfect BAC number, it’s likely that it’s getting more and more expensive to acquire customers.

Long-Term Viability

When a company has an increasing CAC and still hasn’t achieved profitability, you have to ask the tough questions. Step away from the numbers for a second: is Wish something that people like? Have enough people had a good experience with Wish such that they don’t need to be re-acquired with ads?

We can get an answer to these questions by looking at customers reviews.

A quick Google search for “Wish.com reviews” shows the review website SiteJabber as one of the first results. Wish has a 2.47 star rating from 7.1k reviews. This is in contrast to several other retailers:

- Amazon: 4.25 star rating (8.7k reviews)

- Ross: 4.10 star rating (177 reviews)

- Walmart: 3.48 star rating (4.1k reviews)

- eBay: 3.42 star rating (3.8k reviews)

- Overstock: 3.37 star rating (1.5k reviews)

- Zulily: 3.07 star rating (4.3 reviews)

- Groupon: 2.90 star rating (6.4k reviews)

- Wayfair: 1.91 star rating (1k reviews)

So while there are other online retailers that have poor customer reviews (Groupon, Wayfair), it’s not a good sign that Wish is near the bottom.

The positive comments talk about the discounted prices (“Personally, I find them to be about 25% less expensive than Amazon or eBay and look there before anywhere else. They also offer deals and discounts.”) while most of the negative comments discuss long shipping times (“When the delivery date comes they will just change the delivery date without any notice”) or poor customer support (“Terrible after sales support. I ordered a[n] item in my normal size which didn't fit. They asked for photo evidence which was sent but they refused to do anything about it.”).

We won’t know their exact retention unless they disclose it. But I’m hesitant about Wish's growth. Many other eCommerce businesses saw 50-150% digital growth the past few quarters. No matter which way Wish cuts it’s numbers, it can’t present a growth rate higher than 32% in 2020. It makes me wonder if the business has reached capacity for profitable customer acquisition.

The Verdict

Overall, Wish seems a bit sus to me.

While I didn’t do much valuation work in this essay, I’m not sure it makes a huge difference for my purposes. Of course there is a price in which I would invest in Wish, but the price would be too low for them to continue with the offering.

As Warren Buffet famously said, “It's far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.”

I don’t think Wish is a wonderful company. Their top-line growth has plateaued. Their acquisition costs are increasing. Their gross margins are being squeezed by increased international shipping charges. I’m not confident with their unit economics, nor their customer NPS.

Of course, they have some positive attributes as well: eCommerce tailwinds, improving annual cohorts, etc. But it’s a bit too hairy for my taste.

What do you think?

How did you feel about this post?

Enjoy this post? Subscribe to Napkin Math Premium

We’re striving to make Napkin Math Premium the best possible resource for finance and investing analysis.

When you become a member you’ll get additional in-depth articles only available to subscribers, including:

- How Datadog became the $25 billion leader in Observability

- Why The New York Times is going to continue to grow at breakneck speeds

- Why school bus operators are an overlooked investment opportunity, and a database of 60 companies to get you started

Napkin Math also comes as a bundle, so when you subscribe you also get access to all our other paid newsletters: Divinations, Superorganizers, Praxis, Means of Creation, Ask Jerry, The Long Conversation, Free Radicals, and Almanack.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

You should do another post on this

Now that the price has fallen to less than $2.5, would you invest in WISH ? I think it would help to read your perspective on this again - how did the company has done so far (not stock price) and what do you the future hold for WISH. I think reader will enjoy