Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

One of the headier promises of AI is that it will make the creation of goods cheaper. Little robots will automate away rote tasks, dramatically simplifying the production of digital and physical products. In this world, there is an abundance of products, and every industry becomes far more competitive.

How can a startup survive in this environment? The answer is deceptively simple: Have good taste.

Taste is the bone-deep feeling that you’ve made something good. It is a sense, inexplicable and ephemeral. But it’s also a tangible skill that’s increasingly essential. Taste is how a business differentiates itself when attention is scarce and choice is abundant. Knowing what to make is just as important as the ability to make it.

There’s an even bigger challenge needed to build a lasting business: scaling your taste, not just into a single object, but into an organization that can build and distribute many products that reflect that taste.

There are few companies that have successfully scaled taste better than MSCHF (pronounced “mischief”). Well, not exactly a company, as they explained to me when I visited their Brooklyn-based workshop set across the street from a skate park, but an “artists collective that happened to raise venture capital.” Or, according to their self-selected LinkedIn industry category, they are in the business of “Dairy Product Manufacturing.”

The group releases a brand-new product every two weeks, each of which has little physical relationship to the previous drop. Their recent releases include edible AirPod-shaped candy, a perfume that smells like WD-40, and a collaboration with Crocs on a mid-calf boot. In the last five years they have released more than 100 products. Each drop is creative and rebellious, winking to the world that capitalism is a necessary joke. They do all of this with a team of 34 people, most of whom are generalists with no background in making physical goods.

The Croc boot that launched with a Paris Hilton photo shoot. Source: MSCHF.You may think that this is a recipe for disaster, the opposite of most startup advice. Rather than focus on solving a common customer problem extremely well, they do, well, whatever they want. And there’s more weirdness. While MSCHF mostly distributes their goods through channels like email, an app, and social media, they have tried novel distribution techniques that have gotten them banned from Venmo, Shopify, and Twilio. One recent drop I had early access to was distributed with a link to a Google Doc (seriously).

Despite—or because of—these unorthodox practices, the business has been an enormous cultural success. They’ve partnered with celebrities as varied as Paris Hilton ($450 Crocs), Casey Neistat (a single car to which they sold 5,000 $20 keys), and Rihanna (a lip gloss disguised as a packet of ketchup that sold as a six pack for $25). MSCHF is a digitally native brand that has staged high-end art shows in Korea and Los Angeles. They’ve demonstrated a talent for getting journalists to fawn (including this very writer), with coverage in publications like the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and Vogue.

It isn’t just cultural success—they’ve built a real business, too. Four years ago, they raised $11.5 million from investors like Canaan Partners and Trae Stephens at Founders Fund. They’ve hit eight figures in revenue, while having no physical retail location. Their shoes—they’ve made 32 pairs—are enormously popular: They’ve measured demand (via direct sales and drawings where customers enter their credit card numbers with the hope to win) of well over 100,000 pairs, which would’ve yielded $35 million in revenue last year alone. The team was unwilling to disclose how many pairs they sold.

And while there are many companies that have grown faster or had more impressive financial results, what attracted me to MSCHF was how they scaled their taste without compromising on it. They’ve made art their business and their business their art. How on earth do they release so many products while staying true to their original vision? How do they keep their team creative and engaged? Are there lessons anyone can apply from what they’ve done?

This is what I learned.

Scale is not the goal—it’s the process

“Our only goal when we started was to make anything we wanted and only what we wanted.”

Kevin Wiesner, MSCHF’s 32-year-old chief creative officer, was pacing at the rear of MSCHF’s workshop. A graduate of Brown and the Rhode Island School of Design, Wiesner wears square-shaped silver glasses and has long, straight hair kissing the tops of his bony shoulders. Before MSCHF, he was the co-founder of an ad agency that “focused on viral campaigns.”

I had two reactions to his statement: a deep, spiritual-level resonance followed by a wash of skepticism. It landed because I manage my creative process similarly. The day I compromise what I write to satisfy the whims of some corporate overlord is the day that I quit writing for a career. One of the pinnacles of human existence is to align our innate desire to create with our day-to-day labor.

This also sounded like the sort of thing you would say during a pitch to a job candidate (or to a writer profiling your company). What actually makes it possible to “make anything” you want is that crass thing—money. And money, not personal interest, is the deciding factor for what a company is able to make.

To my more business-oriented readers, you may be surprised that this is a surprisingly rare view in the creative world. Marketing, sales, distribution—all of that is seen as a secondary, dirty effort, a necessary evil that degrades the quality of your work.

So I was taken aback by the degree by which everyone at MSCHF embraced the capitalist nature of their enterprise. In this regard, our conversations sounded more like those I’d have with a startup than with an artist’s commune. During multiple visits with the leadership team, I heard the same Andy Warhol quote several times: “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.”

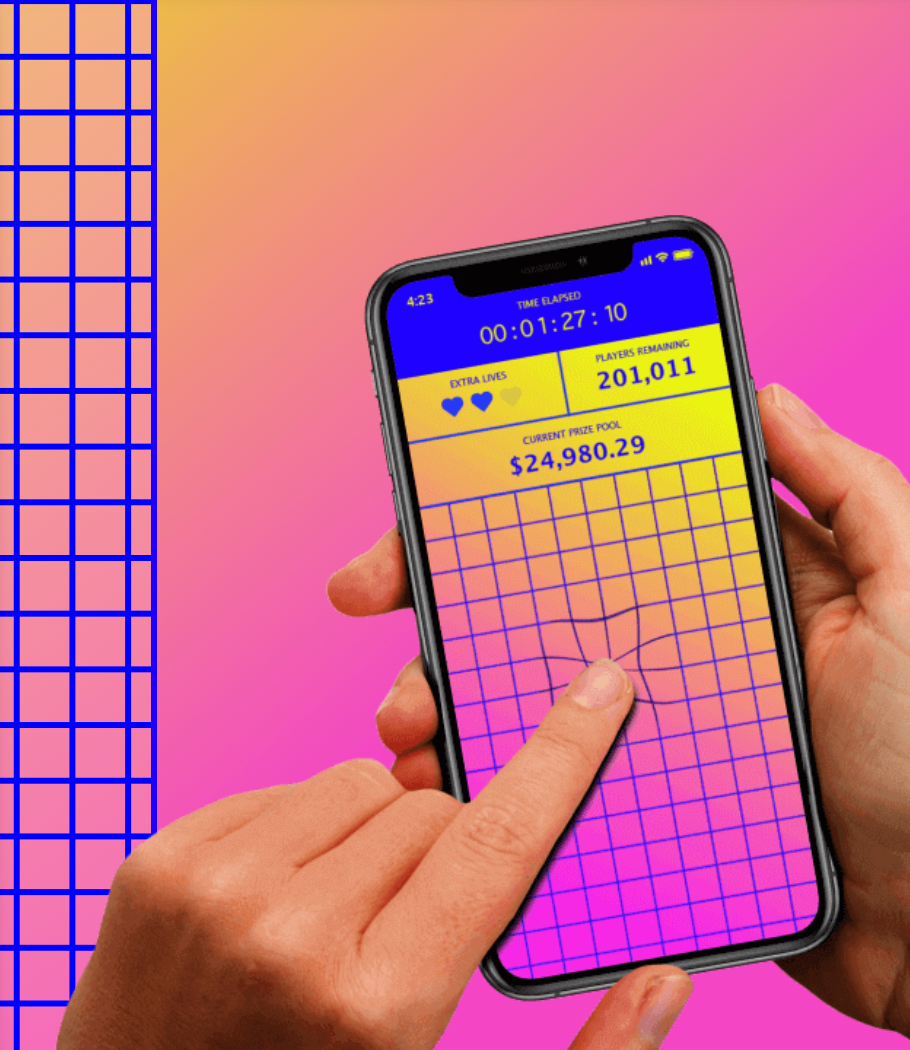

MSCHF’s art is both the objects they create and the business itself. To accomplish this harmony, MSCHF explicitly programs the idea of scaling into their work—not as the business’s goal, but as a key component of the products they make. For example, in July 2020, MSCHF collaborated with MrBeast on a game called “Finger on the App.”

Source: Finger on the App.The game is exactly as it sounds: Users had to literally keep their fingers on the app. If they took their fingers off, they lost. The more people who played, the more pronounced the meta-commentary on how much time we waste playing games on our phone. In the end, after 70 straight hours, 1.1 million downloads, and 400,000 players, Mr. Beast declared the final four players winners, gave them $20,000 each, and told them to go to sleep.

The more people who buy a product, the further the product’s message spreads, the more money the company makes, the more they can invest in their projects. It's a virtuous cycle of creation and consumption. By making scale—the number of people who use or see the creation—an explicit part of the art’s statement, they naturally marry the business’s goals with the goals of the piece.

This marriage of distribution and product was the idea from the very beginning. When founder and CEO Gabriel Whaley first started making things online in the early 2010s, his creations went viral on their own. One early project, a GIF of the three-bubble indicator of someone typing in iMessage, was covered by mainstream media. The 33-year old Whaley wasn’t born on some artist’s commune that implanted this seed of irreverence early. Instead, his story is fairly classic Americana, one of a rural upbringing and lots of soccer. It was only when he started to create stuff online that the ethos that shapes MSCHF today began to germinate.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Brilliant, Evan. Well researched and the context is correct. To be yourself, you have to come to the truth about what that is. Unpack it all. That takes time and repetition. Ah!!! That's the hard part. How many professionals know their truth? Start-up or seasoned business owner?

AWESOME STORY!! Loved the reflections on staying true to your essence in art and the actionable advice on how to do that

Enjoyable read with a great message.

Maybe I missed it: are they profitable? Do they experience turnover? Do they expand their employee count?

@adam_1790 didn't get a P&L unfortunately!

Great read! Really cool to get an insight in such an unusual company. It does feel like their dedication to 'taste' is similar to how some companies look at their culture. Where there any practices or something like that in place to reinforce their culture?

Wow, this resonated hard. The pull between staying true and compromising to corporate? That's real.