What exactly does a university sell?

You might say they sell training and skills to help students earn a job.

You might say they sell a space for young adults to explore their intellectual and occupational interests in a low-risk environment.

You might say they simply sell a stamp of approval; a guarantee that students won’t fall into the cracks of society.

Or maybe they just sell a year-long summer camp to have fun, meet lifelong friends and let loose.

The truth is that universities sell all of these things, bundled together. And that’s a big reason they’ve been able to raise prices to astronomical levels over the past several decades — it’s really hard to disrupt all of those things at once.

Now, when any industry raises prices and inflates costs, it will start to attract hungry entrepreneurs trying to change the status quo. Education is no different. But despite many attempts, there have been very, very few billion dollar education companies. Education technology (edtech) is just really tricky to build in.

In fact, one of the few success stories in edtech is a company that doesn’t really sell education at all: MasterClass.

Instead of competing with universities at their own game, MasterClass took a different route. They hired experts and celebrities — practitioners who are at the very top of their field — and made beautiful, highly-produced videos of them explaining their craft. MasterClass might claim to be selling education, but don’t be fooled: they are selling credibility and inspiration.

So what can we learn about MasterClass’s business and how they’ve grown to over 9-figures in annual revenue?

How MasterClass Works

MasterClass is an online education portal. It works like this: you pay $180 for an all-access annual pass to tutorials and lectures by experts in various fields. For example, you could learn tennis from Serena Williams or you could learn filmmaking from Martin Scorsese. Each lesson includes several pre-recorded videos, workbooks, activities, and notes.

When an expert works with MasterClass, they are cited to earn $100,000 up front, along with 30% of the ongoing revenue generated from their classes.

CEO David Rogier recognizes that most of the experts don’t actually do it just for the money, but also as a way to give back. For them, it’s an easy way to share their story and give advice to a lot of people. A one-year subscription priced at $180 is pretty accessible — certainly cheaper than getting advice from them directly.

Additionally, I’m sure MasterClass makes it super simple for creators to record and produce their classes. It’s a win for everyone: experts get more reach and a bit of money, customers get advice from the best, and MasterClass earns revenue for making it all come together.

While the business is a cool idea, its success is even more impressive.

MasterClass doesn’t officially publish its revenue, but we can get a pretty close estimate. In 2018, Rogier mentioned that it would match Udacity’s $70 million in revenue (source). If that’s the case, it’s not hard to assume 2019 revenue was around $140 million — the business has been doubling each year for several years.

And if they kept increasing revenue at the same pace (perhaps with a bit of a “COVID premium” due to more people consuming content at home) then it wouldn’t be a stretch to guess that mid-2020 revenue might clear $200 million.

Regardless of the actual figure, getting to nine figures in revenue in under five years is incredible. Especially for a media or education startup — there have been very few unicorns in these sectors.

Credibility, Not Education

Even though MasterClass has instructors such as Aaron Franklin, Hans Zimmer, deadmau5, and Neil deGrasse Tyson, MasterClass isn’t selling a plate of barbeque, a film score, an EDM track, or a physics degree. Nor is it selling how to explicitly become someone who can create one of these things.

Rather, Masterclass is selling credibility.

It’s relatively easy to make and distribute educational content. Even high-cost content isn’t hard to replicate; it’s just expensive. However, the scarcity in the education world isn’t the advice itself, but rather the credibility behind it: The credibility of being someone at the top of your field takes a lot of work. It’s hard — dare I say impossible — to game that kind of system.

Consider this: if you walked into the bedroom of an 11-year-old kid who loved basketball, what would you see on their wall? My guess is it would be a poster of LeBron James jumping high into the air and slamming the ball over a stretched out opponent. That 11-year-old looks up to LeBron James, wants to be LeBron James. He can do anything.

To become just like LeBron, that same 11-year-old kid might spend all day shooting free throws, shuffling their feet along the baseline, and practicing their shooting form. Or, if they had the resources, they might go to a summer basketball camp or hire a private skills coach. These are the hard and repetitive tasks that you have to do to become great at basketball.

But the spark that ignited it all — the whole reason that the kid puts in the hard work and asks his parents to go to a basketball camp — came from admiring the best of the best.

Masterclass is selling the LeBron James poster we put on our bedroom wall, not the skills coach we hire to train us three times a week. And they’ve learned that adults aren’t so much different from our 11-year-old selves: we love to be inspired by the greatest humans on this planet.

(I actually think this is what massive online open courses (MOOCs) got wrong. They have notoriously low completion rates (around 5%), which is generally cited as the reason they didn’t upend the education system. But I think their mistake wasn’t in that people weren’t finishing the courses. Instead, it was the thesis that online, low-touch courses were for skill-building instead of inspiration or entertainment. Maybe if companies like Coursera and Udemy would’ve leaned into edutainment instead of job preparation it could’ve been a different story.)

Evergreen Content

One of the biggest reasons investors and customers alike love MasterClass is because they are building a repository of evergreen content — perhaps some of the longest-lasting stuff on the internet.

Think about it this way: if you would watch a writing class from Judy Blume, wouldn’t you also watch a writing class from other great American writers like Ernest Hemingway or John Steinbeck? See, there’s a threshold. Call it the “greatness threshold”. If a person crosses this greatness threshold, they are admired across generations. And that's what MasterClass is building.

Co-founder Aaron Rasmussen has even mentioned that this is a goal for the company:

“It’s funny, people kept coming in, and you know, we’re having to hire a ton of people, et cetera. And they would be like, ‘What’s your four-year plan?’ And I would say, ‘Well, I’ll tell you what our hundred-year plan is. And we’ll wind it back 96 years and we’ll get to the first four years, but the hundred year plan is, 100 years from now, there should be a group of people capturing the knowledge of the world’s greatest — crystallizing it, and disseminating it, that’s my goal. But also, 100 years from now, the things we make today should hold up. They should be worthy of that.” [Emphasis mine]

The actual advice isn’t the limiting factor — in 2020, information is plentiful. However, the success to back it up is what’s in short supply. While lots of people can opine on how to get to the top of a particular field, only the best can speak to their own experience when they tell you how to get there. The authenticity can’t be copied. And that’s why the content will last a very long time.

Advertisements as a Product

MasterClass also has best-in-class advertisements. No really, they are amazing. Perhaps drawing on the Hollywood background of some of their celebrities, MasterClass made sure that the advertisements were just as great as the content behind the paywall. And while they may pay Facebook to promote their ads, they also spread on their own.

As an example, take a look at this video for a MasterClass by Neil deGrasse Tyson.

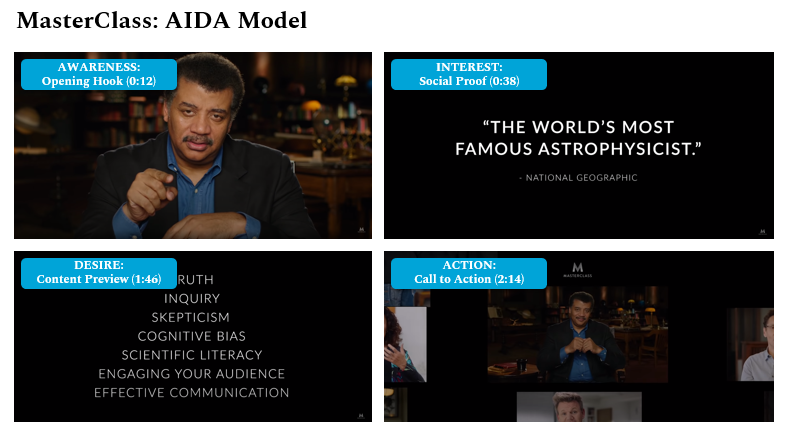

Each of their advertisements is entertaining in its own right. The opening line hooks you in and you can’t help but keep watching: “One of the great challenges of this world is knowing enough about a subject to think you’re right, but not enough about the subject to know you’re wrong,” proclaims deGrasse Tyson in his deep, crisp voice. The ads are well-written, well-produced, and a joy to watch.

But the best part is that while MasterClass is telling great stories, they are also roping you into a sales process. One of my favorite marketing frameworks is called “AIDA”. It assumes the buyer goes through a linear process of awareness (A), interest (I), desire (D), then action (A). If you look closely enough, the MasterClass ads follow this model pretty closely.

You want to watch the ad. Then you want to watch more.

This is important for two reasons. First is that it actually lowers paid acquisition costs. It lowers them because the Facebook Ads algorithm rewards engaging advertisements with lower CPMs and lots of distribution. Facebook does this because engaging advertisements are just like engaging posts: they keep people on Facebook.

So from MasterClass’s perspective, having incredible ads actually makes serving them to an audience cheaper.

Additionally, organic marketing is usually cheaper than paid marketing. MasterClass certainly used these videos for paid advertising, but they are so good that they also generated a lot of views on their own. The Neil deGrasse Tyson advertisement alone has almost 23 million views. (I even show the ads to my friends because they are so delightful to watch!) Add in the fact that the videos are both a great story and great marketing tool and it’s no wonder MasterClass ads have done so well.

Key Takeaways

So what are the biggest takeaways from MasterClass’s success?

Borrowing social capital is easier than creating it. MasterClass took people who were already famous and gave their fans even more access to them (without much burden on the celebrities). It’s tricky to create a world-class talent. The MasterClass model skipped the line of building a large audience and lots of credibility and instead, they purchased under-monetized social capital and made delightful educational content out of it.

Small bets lead to bigger bets. In hindsight, this idea seems obvious. But when the company started, nothing like this really existed (recall that Cameo was started a full two years after MasterClass launched). And while MasterClass has nearly $240 million in outside funding now, they tested the idea in 2015 with about $5 million. After getting more than 30,000 initial signups, they were able to raise more and more capital to expand the idea.

I bring this up to compare MasterClass to another large media experiment — Quibi. They had similarities: both of their products had high production costs. They also both leveraged some of the most talented and famous people in the world. But MasterClass did something different than Quibi: it took things step by step. Raise enough to test a hypothesis, and if it works, raise more. And that’s a lesson investors and operators alike can always be reminded of.

Advertisements shouldn’t be an afterthought. Several direct-to-consumer fashion and lifestyle brands know this already — they live and die on their social media presence. However, advertisement quality matters a lot more for industries like education, software, and media than you might think. In the words of Matthew Ball: “[I]f media matters to consumers, but they won’t spend a lot on it, the efficient use of content is actually to drive other industries, categories and products that have better (and bigger) economics.”

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!