Roll-up strategies are common in private equity, but scarce in startups. They are often executed behind closed doors in antiquated and boring industries. A near-arbitrage investment strategy, there’s no reason for buyout investors to share their ideas. And because they operate in the private markets and require millions in capital to execute, there are few reasons why most people would dig into them.

But recently, at least one startup has learned about this strategy and is capitalizing on it.

Thrasio, a company that buys Amazon third-party private-label businesses, recently raised $260 million in funding, giving it a valuation of over $1 billion. According to the Washington Post, they have over $300 million pro forma trailing twelve months revenue.

At a $1 billion valuation in two years, Thrasio is the fastest profitable company in the U.S. to become a unicorn. In this article, I explore how Amazon Marketplace businesses work, Thrasio’s operating strategy, why they are subject to platform risk, if regulators will intervene if Amazon changes their algorithm, and what a “Thrasio for X” could look like. Let’s get into it.

How Amazon Marketplace Works

Amazon Marketplace is a platform for independent eCommerce sellers and it’s split up between fulfilled by Amazon (FBA) and fulfilled by merchant (FBM). 66% of Marketplace businesses sell only using FBA, 6% sell only using FBM, and the remaining 29% fulfill their products both through Amazon and their own networks (source).

Fulfilled by merchant (FBM) is similar to traditional eCommerce models: the merchant sells a product (in this case through Amazon) and on the backend they handle everything. They buy or manufacture the product, they ship it, they handle customer support and returns. For FBM businesses, Amazon is a marketing channel.

Fulfilled by Amazon (FBA) is a bit different. It works like this: the merchant still sells a product through Amazon, but in this case Amazon does all the fulfillment work. According to their website, Amazon offers shipping, storage, removals and returns. They hold your inventory, monitor it through their tracking system, pack and ship the product, and deal with returns. Many times these businesses have products that are sourced through a Chinese factory, shipped to an Amazon warehouse in the US, then shipped to the customer by Amazon.

With Amazon FBA, it’s entirely possible to start and run an eCommerce store sitting in your basement and wearing your pajamas. It’s a great option for resourceful entrepreneurs, especially those who don’t have other technical skills like programming.

Most of the businesses on Amazon’s third-party marketplace are relatively small. There’s a lot of advice online about how to build these, and one of the most common best practices is to pick a small niche. Products sold by FBA businesses range from blood pressure monitors to hair sprays to children's toys and everything in between.

Amazon Marketplace (where FBM and FBA companies live) is no small business for Amazon. The gross merchandise volume (GMV) of Amazon is $335 billion annually, and $200 billion of that is Amazon Marketplace.

It’s actually been one of the main growth drivers for the retail business and now makes up nearly 60% of all sales on Amazon.com.

(Source)

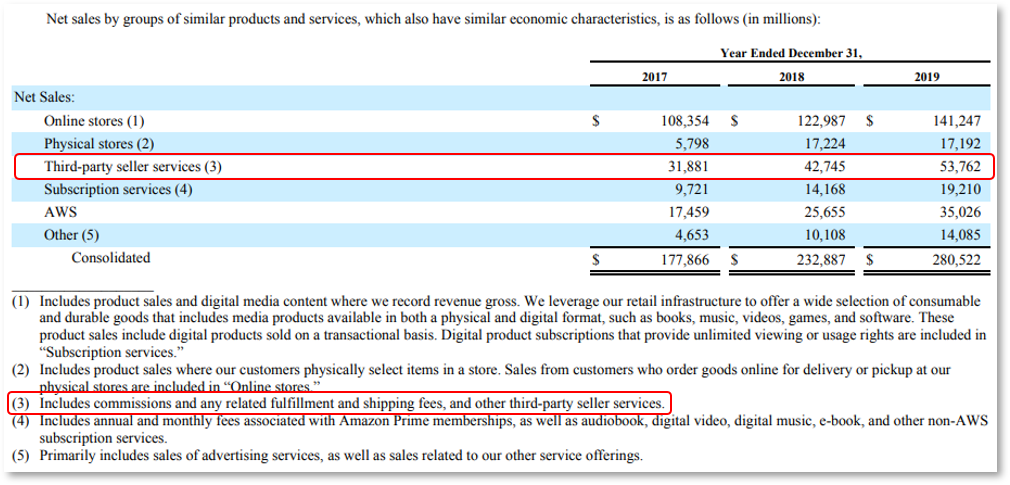

Amazon of course just gets a cut of the marketplace revenue. In 2019, they earned $53.7 billion, implying a ~27% take rate.

(Source: Amazon 2019 Form 10-K)

Thrasio’s Strategy

From the outside, Thrasio’s strategy is simple. They buy under-optimized businesses in a highly-fragmented industry. Then, they improve operations, mash together the backends and either milk the cash flow for dividends or sell at a higher multiple.

As a profitable company with over $300 million in revenue, their plan is working so far (we’ll get to the risks in a minute). It’s working because they can expand their earnings multiple, they’re operating in a large total addressable market (TAM) and they work to build competitive advantages in their business.

Multiple Expansion

There’s a common strategy in private equity that goes something like this. There’s a very large market and the market is very fragmented. It’s not monopolistic or ologopic: there are many small businesses and none of them own a large market share. In this environment, a buyout firm buys a bunch of the small businesses — usually with some sort of similar characteristics. Once they are under the same ownership, they can sell the combined company for a higher EBITDA multiple.

There’s a few reasons this happens. First, small businesses usually have a lot of dependence on the owner / operator. There are many businesses that have $100k - $5.0m in EBITDA that are family owned and have been for years. It’s not that these businesses aren’t managed well, but sometimes they just aren’t optimized. There are things like digital marketing, back office automation and owner compensation that can all be adjusted to make the business a bit better.

And not only can a small business sometimes be run more effectively by a sophisticated buyer, but just by becoming a larger business the earnings become more valuable. There are debates on why this is truly the case, but one explanation is that it takes a certain amount of scale to get to the point where the business can run without the owner / CEO having a meaningful operational impact. Think of the extremes: a single-person consulting business goes to zero if the consultant stops working, but Microsoft — with 144,000 employees — could easily maintain operations if Satya Nadella stepped down.

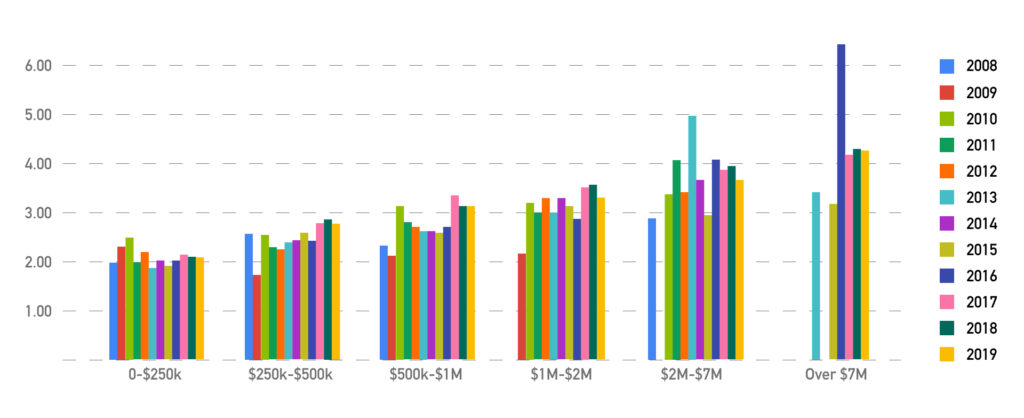

There’s also data to back this up. DigitalExists, an internet business broker, published a post that compared the earnings multiples of transactions, segmented by size, year, industry and other parameters.

The most telling chart shows the relation of size to earnings multiple. In 2018 the average multiple for a business that sold under $250k was 2.06x, while the average multiple for a business worth over $7 million was just over 4x (with a gradual increase in between).

As you might imagine, Thrasio isn’t the first company to execute on this strategy (or a variation of this strategy). Some of the most successful private equity firms in the world do this kind of thing in every industry you can imagine. I’ve seen rollups in vertical market software, consumer services, manufacturing, industrial services, healthcare services and many others. If there’s a large and fragmented market (a real large and fragmented market, not mere banker-talk), there’s a roll-up opportunity. But this is one of the first times that someone is trying to do it on a digital platform like Amazon.

Large TAM

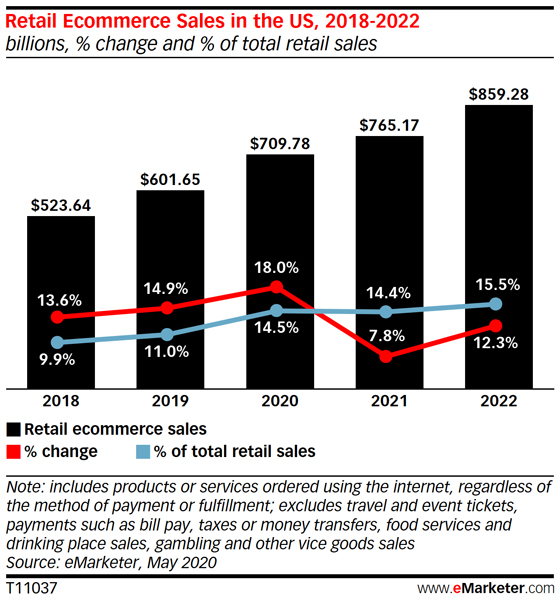

Of course, generating multiple expansion only matters if you can do it for a lot of businesses at once. Fortunately, for Thrasio, their TAM is massive. As mentioned, Amazon Marketplace does $200 billion in sales globally. But just in the US, eCommerce has grown to 14.5% of a $709.78 retail market. It will continue to grow.

(Source)

Performing a roll-up strategy in a fragmented but growing market is a juicy proposition to any enterprising deal-maker.

Competitive Advantages

Besides combining these businesses together, Thrasio has other plans to make operational improvements. While we don’t have insight into what they are doing day-to-day, we can infer some things.

Thrasio’s job postings show hiring across four main departments: creative (copywriting and design), paid marketing, data science and supply chain. Just from this, we can tell that Thrasio will make better site pages, improve marketing efficiency, uncover new opportunities and optimize the supply chain. Combining these functions across several businesses gives them an advantage over individually-owned businesses and also might surface opportunities to integrate businesses on a deeper level.

The other important characteristic of Thrasio is the expertise they are developing in the deal process of purchasing Amazon FBA businesses. With such a massive TAM, this space is competitive. For example, Perch raised $8 million in funding in April 2020 to do the same thing. I can also confirm from private conversations of at least one private equity fund interested in this strategy.

If Thrasio has any sustainable competitive advantage, it is the speed and efficiency of its acquisition process. They’ve acquired over 40 businesses now and broadcast a 45 day close process on their website. In a large, fragmented, growing market that rewards buying small businesses, isn’t a fast closing process the best thing to be good at?

Platform Risk

The biggest risk with their strategy is platform risk. Each of these brands exists on Amazon and Amazon has the power to change their search algorithm at any time to prioritize their own in-house products. If that were to happen, Thrasio brands would be in trouble.

So will that happen? What are the chances that Amazon changes the algorithm? We have a few examples from other platforms of what can happen when companies rely on a platform. Both Facebook and Google have changed their product to minimize the effect of companies built off their platform.

For example, Zynga grew up on Facebook’s growth. Or rather, drove Facebook’s growth. At one point, over half of the United States was playing Zynga games. For a while, Zynga’s incentives were aligned with Facebook: Farmville, a Zynga game, became a viral hit. So much so that people would convince their friends to get a Facebook account just to play Farmville. In fact, when Facebook IPO’d investors were concerned that they earned 12% of revenue from Zynga games.

In 2012, Zynga’s stock plummeted. While there were several reasons (games are a hit-driven business, talent left due to IPO payouts, etc.) one of the main ones is that Facebook games were down. Investors didn’t like that Facebook was so dependent on another company for it’s revenue, so Facebook adjusted their strategy to diminish the power of Zynga. It also helped that they owned the customer relationship: Zynga tried to launch an independent site, but it went nowhere. But everyone who created a Facebook account for Zynga games still had a Facebook account.

Another interesting example of platform dependence is Demand Media with Google search. Demand Media was the OG content farm: they would find search terms on Google like “How to make fabric whitener” or “10 Best Mixers for Tequila” and churn out articles to fill them. In their heyday, they made over 5,700 pieces of content per day; writers often had less than 30 minutes to create a 600 word article.

The business worked for a while. Their articles ranked 1 or 2 for long-tail Google searches. For any Google search, users click first spot an average of 43% of the time while they click on the second spot an average of 37% of the time. Once people clicked on the Demand Media articles, they could sell banner ads against that traffic. At one point they had 86 million unique visitors to their websites every month and eventually filed to go public.

But then in February 2011, Google released their infamous Panda update. The update made dramatic changes to the search results. Their goal was to increase the quality of their results and Demand Media’s articles were hit the hardest; they had set up their entire business to produce high-volume articles that weren’t necessarily high-quality.

This hit Demand Media especially hard because of their reliance on search engine optimization (SEO) as a main distribution channel. Very few people typed Demand Media’s websites directly into their browser. Instead, they would only find their articles through Google. So when Google changed their algorithm, Demand Media was crushed. The company still exists today as Leaf Group but trades at less than 5% of their peak market cap.

Regulation

Now, these examples don’t exactly match what Thrasio is doing. Thrasio doesn’t build games or write content — they sell physical products over the internet. But these case studies do provide a warning sign: if you rely on a platform for distribution, it can get taken away.

Thrasio is already one of the top 25 sellers on Amazon. If they continue to roll-up these businesses and become a multi-billion dollar company, what does Amazon do? If they get too big, would Amazon move their own products higher in product search results?

Regulation naturally enters the discussion. Should Amazon even have the power to put their own products ahead of FBA businesses? The armchair argument for regulation would be that Amazon’s retail business should be a free market. Amazon should be able to try and compete with 3rd-party sellers for the highest search results, but manipulating the results in their favor seems like a step too far. But of course, Amazon might not agree.

Let’s say that Amazon does try and change the search results. Does the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) stop them? A good way to look at this is to compare it against past antitrust regulation.

In February 2020, we got a good look at how regulators think about antitrust, particularly with internet businesses. Two things happened: first, Edgewell Personal Care (the parent company of Schick) tried to buy Harry’s, a razor company, for $1.37 billion. However, the FTC shut it down, citing that it “would eliminate one of the most important competitive forces in the shaving industry.”

Then, just a few weeks later, Credit Karma — a company known for lots of content marketing and free credit score checks — was purchased by Intuit, the owner of several consumer software businesses including TurboTax, Mint and Quickbooks, for $7.1 billion. The deal was reviewed for antitrust concerns but is on track to close.

Now, I’m not an antitrust expert. But a Stratechery post on this topic makes a compelling argument for why this is weird. Even though CreditKarma and Intuit’s products don’t have the same business model, CreditKarma gives them something even more important than scale: customer acquisition. From the piece:

What is actually valuable are Credit Karma’s users — 90 million of them in the U.S. alone, 50% of whom are millennials. Those 90 million users don’t just visit Credit Karma directly, they have already shared substantial amounts of their personal financial data, and have consented to receiving emails about their credit scores. They are, in other words, the best possible customer acquisition channel for a company like Intuit, and for all of the reasons I just recounted, customer acquisition is the most valuable part of the digital value chain. Intuit will gladly suffer a tax filing competitor as long as it has the best possible channel to acquire the next generation of tax filers. [Emphasis mine]

Bringing the conversation back to Thrasio, how would the FTC feel about Amazon? On one hand they might see it through the lens of Harry’s / Edgewell: removing competition in several product categories. But they also might see it through the lens of Credit Karma / Intuit: the companies are in different enough business lines, and Amazon is merely a customer acquisition channel for these brands.

[Editor’s note: if anyone has opinions or insights on this section I’d love to hear from you!]

Final Thoughts

Thrasio represents a new kind of roll-up: a digital roll-up. They are buying small businesses built on one of the largest online platforms in the world. With it, they will capture economies of scale.

One could imagine using this strategy on other large internet platforms. Could Thrasio’s strategy be applied to Twitch creators, Substack writers, or App Store apps?

Each of these platforms has different risks. Thrasio’s biggest risk with Amazon is platform risk. To mitigate that, they could spin up Shopify stores for each of their brands and slowly migrate them off of Amazon. Or they could hope that regulators keep Amazon from changing their ranking algorithms.

But other platforms introduce other risks. Creator-led businesses (with Twitch streamers) might have less platform risk. If they have a strong connection, their fans will follow the creator across platforms. But, those creator-led businesses introduce “key person” risk: if something happened to the creator, the business would be worthless. There’s no perfect strategy here, but that’s also the fun of it.

There will be many more small businesses created on the internet in the coming years. And where there’s money being made, you’ll find investors. It’s only a matter of time before we see even more digital roll-up strategies across industries internet-wide.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!