The first draft of the acclaimed biography The Power Broker clocked in at 1 million words. Author Robert Caro spent seven years of his life on it, crafting a magnum opus about the life of New York City municipal builder Robert Moses. It’s considered one of the greatest nonfiction works of the 20th century—less of a biography and more of a sweeping, detailed study about the nature of power.

As Caro’s first published book, it was a portent of the kind of story he’d spend the rest of his life telling. He became famous for his detailed, meticulous approach to biographical research, sometimes taking a full decade to complete a book. Since the 1970s, he has focused his efforts on a five-book series about President Lyndon B. Johnson. Fans are anxiously awaiting the final installment, which he’s been working on since 2012.

You can imagine just how hard it would be to make sense of a decade’s worth of research, let alone bring it all to life in a compelling narrative. There’s a lot we can learn from Caro’s methodical approach to note-taking and writing.

We mere mortals can peek behind the scenes of his work by visiting the oldest museum in New York City—the New-York Historical Society. It acquired the rights to Caro’s archives and turned them into a permanent exhibit, with plans to rotate the collection of documents over time. The exhibit displayed different stages of his writing process, from interviewing to outlining, so I picked some highlights to share below.

The research room

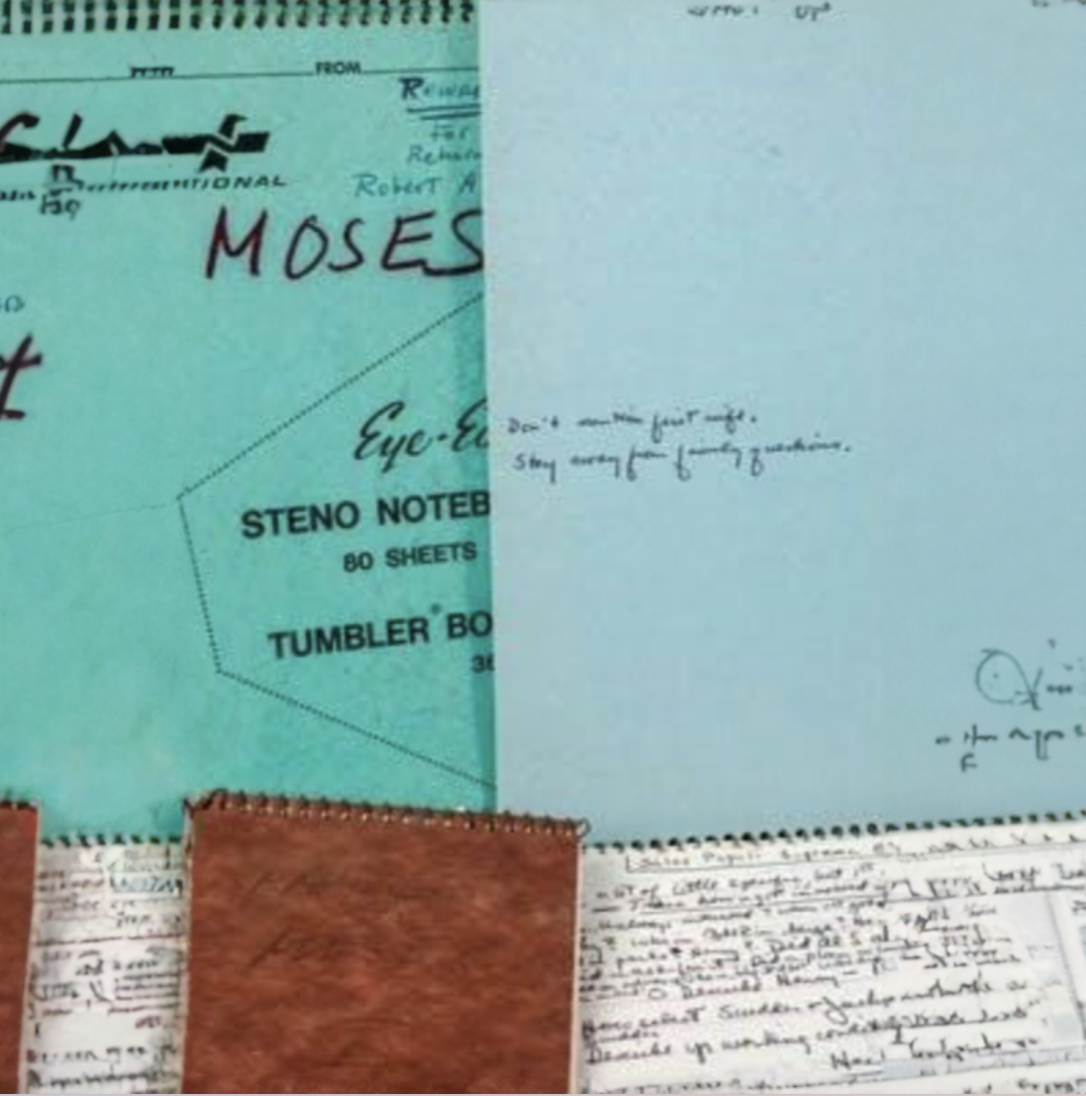

Even though his readers usually have to wait at least 10 years between books, Caro jokes that he’s actually a very fast writer. It’s the research that takes forever. He has a deep appreciation for truth in all its complexity, jotting down copious notes through every stage of the process, all of which wind up in carefully labeled files. He devoted an entire room in his house to documentation.

Caro’s files on Robert Kennedy. Source: screenshot from “PBS Newshour”Before he kicks off his original reporting for a book, he first reads every piece of secondary material on his subject (and time period) he can get his hands on, from other seminal books on them to national and magazine stories from the time, followed by small-town newspaper articles.

In the case of his Johnson series, Caro has dug into the government documentation not just of his main subject, but of every president Johnson dealt with, from Roosevelt to Eisenhower. To give you a sense of the scope, each set of these presidential papers, held by the Library of Congress, are hundreds of thousands of pages in length. Caro reflected on the scale of the task to the Paris Review:

[T]he LBJ Presidential Library is just massive. The last time I was there, they had forty-four million pieces of paper. These shelves go back, like, a hundred feet. And there are four floors of these red buckram boxes. His congressional papers run 144 linear feet. Which is 349 boxes. A box can hold eight hundred pages. I was able to go through all of those, though it took a long, long time.

To more fully understand Johnson, Caro and his wife, Ina, moved to LBJ’s hometown in rural Texas Hill Country. Living there for three years gave the Caros an intimate sense of how the future president grew up.

Caro recounts a Hill Country woman challenging him to lift a bucket of water, pointing out that as a city boy, he didn’t understand just how heavy it would be. Hill Country residents had to lift dozens of these buckets a day to keep their farms watered in the early 20th century. As Caro found, reading gives us access to one kind of information. The body has a different sort of truth.

There are many other stories like this that show Caro’s dedication to his projects. As he put it: “The more of those facts you get… the closer you’re coming to whatever truth there is.”

‘Endless’ interviews

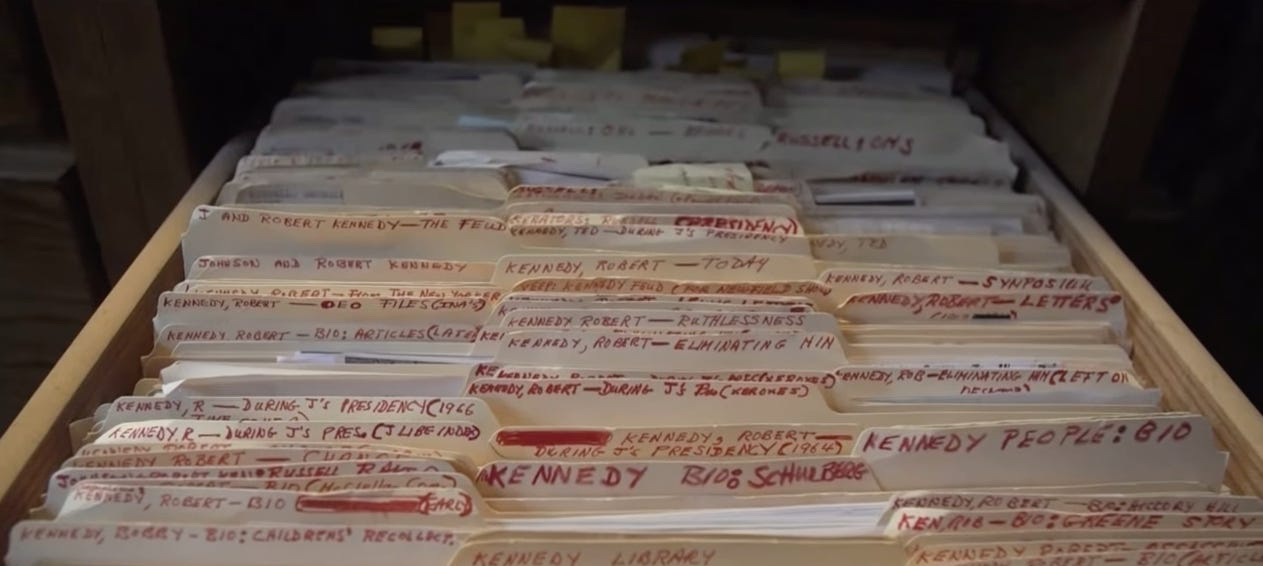

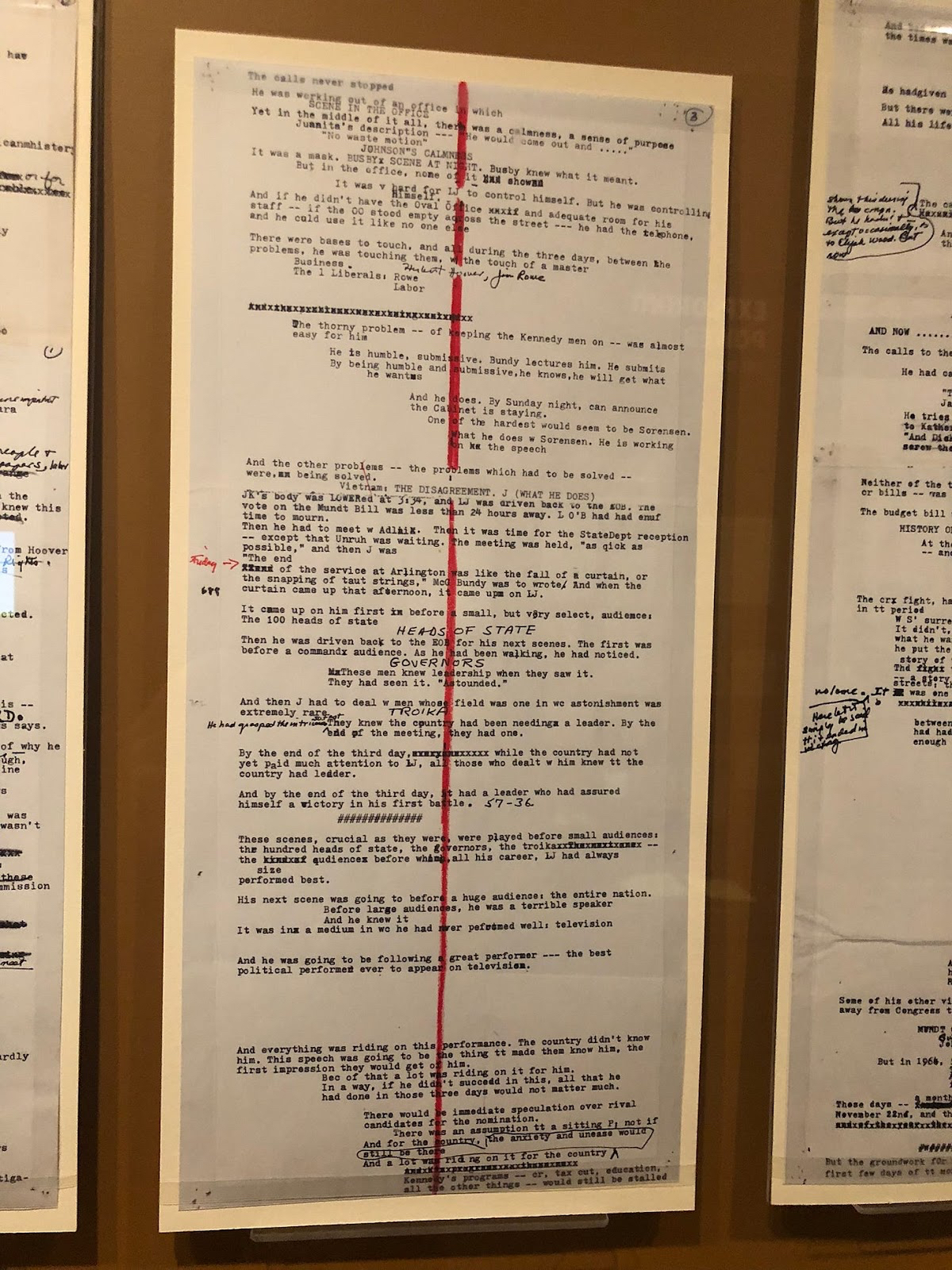

Source: New-York Historical SocietyInterviewing was another key part of Caro’s information gathering process. He interviewed even seemingly minor characters in LBJ’s life (like a chauffeur) 10 to 20 times. He understood the psychological process of getting people to open up and would cross-reference his conversations, bringing up details one person said to another to help jog their memory or coax details out of them.

As Caro told the New York Times: “I did 22 formal interviews with Johnson’s speechwriter Horace Busby. If you look through these interviews, you say, ‘Boy, what he’s telling you about something in the first interview isn’t what he’s telling you about that same thing in the 10th interview.’”

In the archive exhibit, his notepads are filled with tactical reminders to himself. For example, to make sure interviewees have silences to fill, Caro has scribbled “SU” throughout his notes—a reminder to himself to shut up.

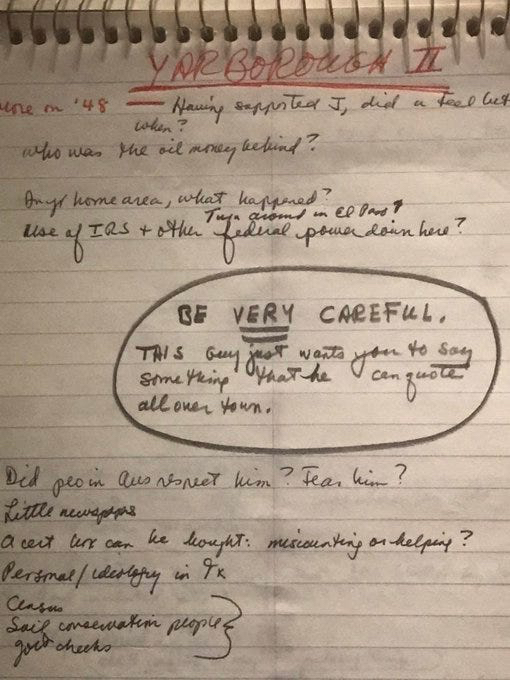

He was also concerned with his interviewees’ motives. He didn’t set out to be a biographer; he was interested in power: what it is, how people get it, and what they do with it. So in the notes for one conversation, he warned himself: “Be very careful. This guy just wants you to say something that he can quote all over town.”

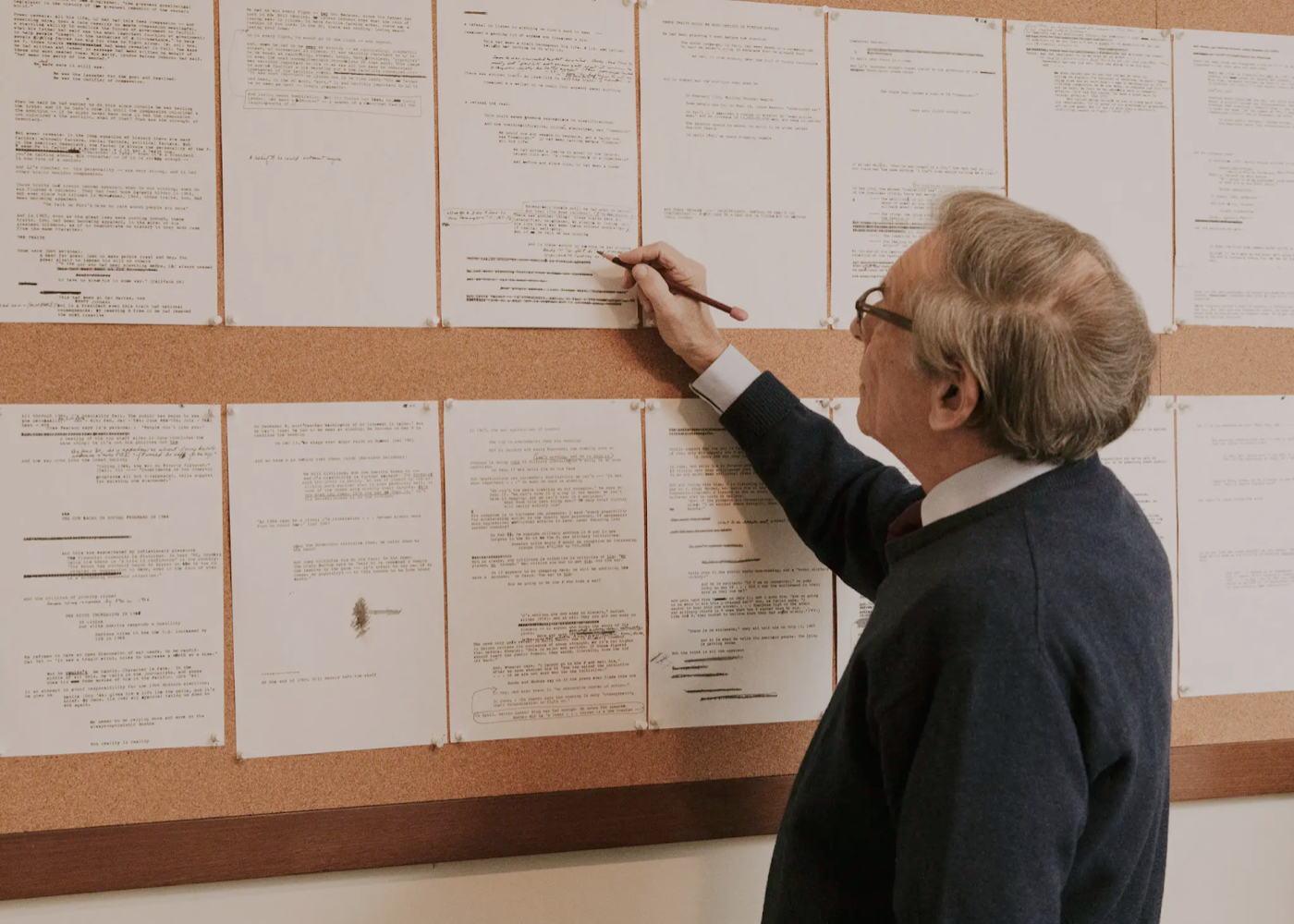

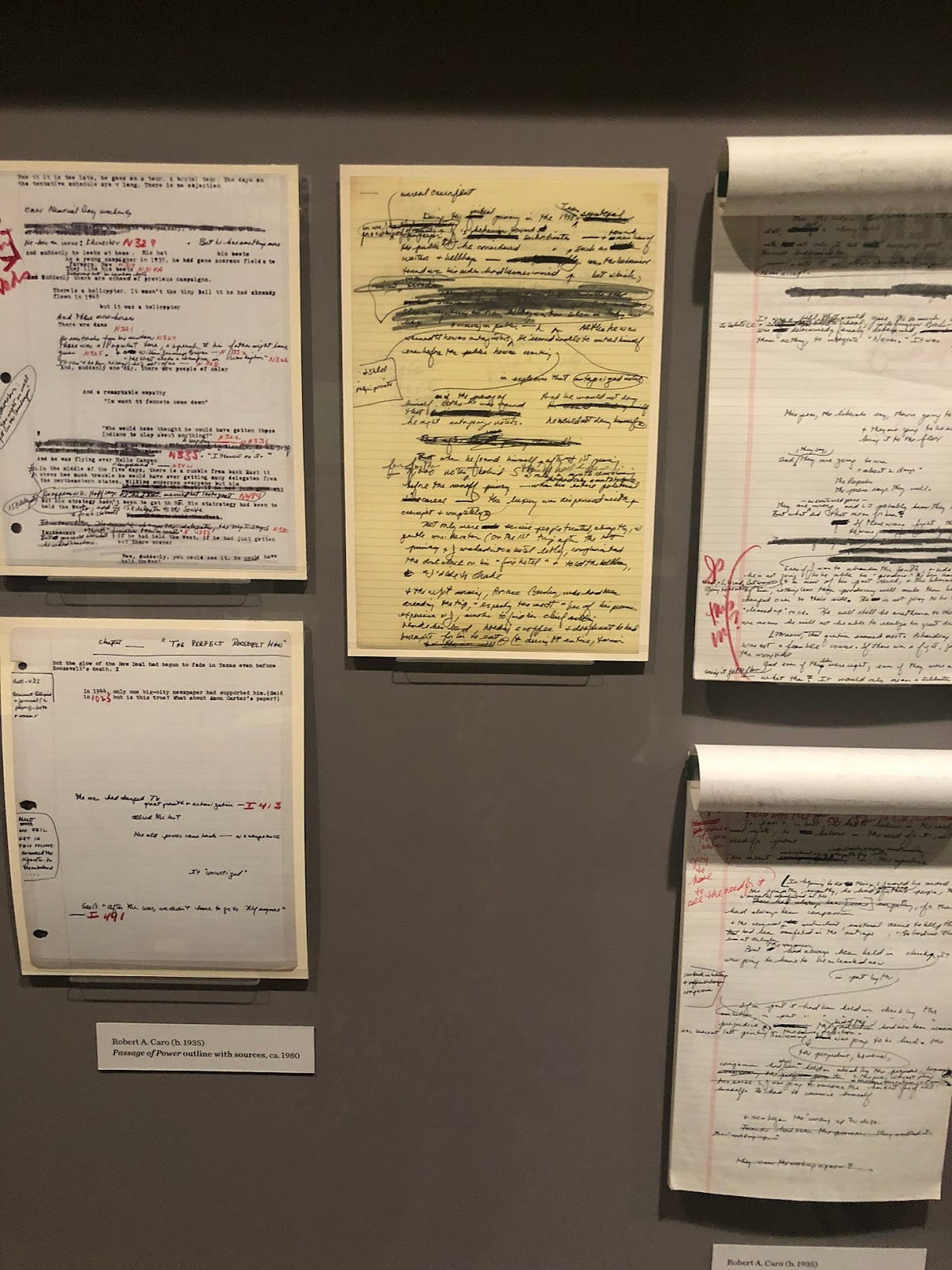

Caro’s iconic outline board

Caro, editing outlines on his cork board. Source: New York Times/Landon SpeersWith all the information Caro collects, outlining is a key stage of the organization process. He works in an atomic fashion, first summarizing the point of his book into 1-3 paragraphs.

He then creates a macro outline for the book, and separate individual outlines for each chapter, which function as “the chapter in brief, without any of the supportive evidence.” Each chapter also gets assigned a notebook that holds all the details from his interviews and research—the supporting documentation.

Source: New-York Historical SocietyCaro famously pins his outlines on a cork board in his office, and sometimes has to ward nosy fellow journalists off from reading them. Once he has finished working on a page, he draws a line through the center.

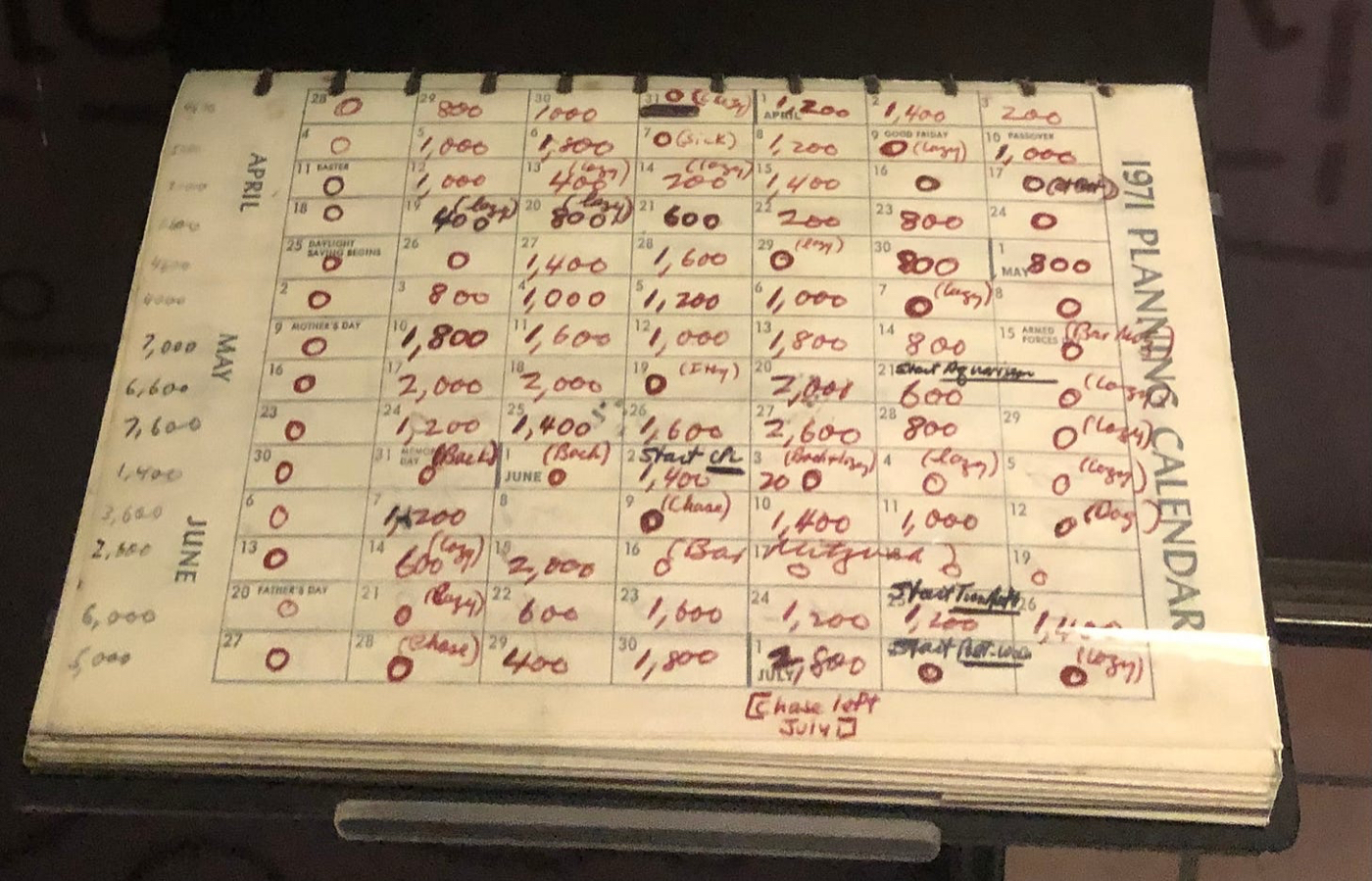

Source: New-York Historical SocietyTracking word count

Once he gets to writing, Caro aims for 1,000 words a day. Sometimes he exceeds his goal. Sometimes he falls short.

As you can see in the below 1971 calendar, Caro held himself accountable while writing The Power Broker. On the far left hand side, he marks the total word count for each week in a column. For every day that he writes zero words, he documents a reason such as his son (“Chase”); travel (“Italy”); or just plain fatigue (“lazy”). Even with his ambitious working schedule, Caro reserves Sunday for rest.

Source: New-York Historical SocietyWriting is hard work. And it’s comforting to know that even Caro had days when he felt “lazy.” Seeing this part of the exhibit, I reflected on the fact that I used to religiously document my word counts, and considered whether it was time to get back to it.

As you can imagine, a decade’s worth of research and writing lends itself to very long books. But Caro never cut corners on the storytelling, investing just as much effort into his prose as his fact-gathering. He rewrote his introduction to The Power Broker “endless” times, experimenting with sentence rhythm and scene setting. “Mood matters. Sense of place matters,” he said. “All these things we talk about with novels, yet I feel that for history and biography to accomplish what they should accomplish, they have to pay as much attention to these devices as novels do.”

To-do lists

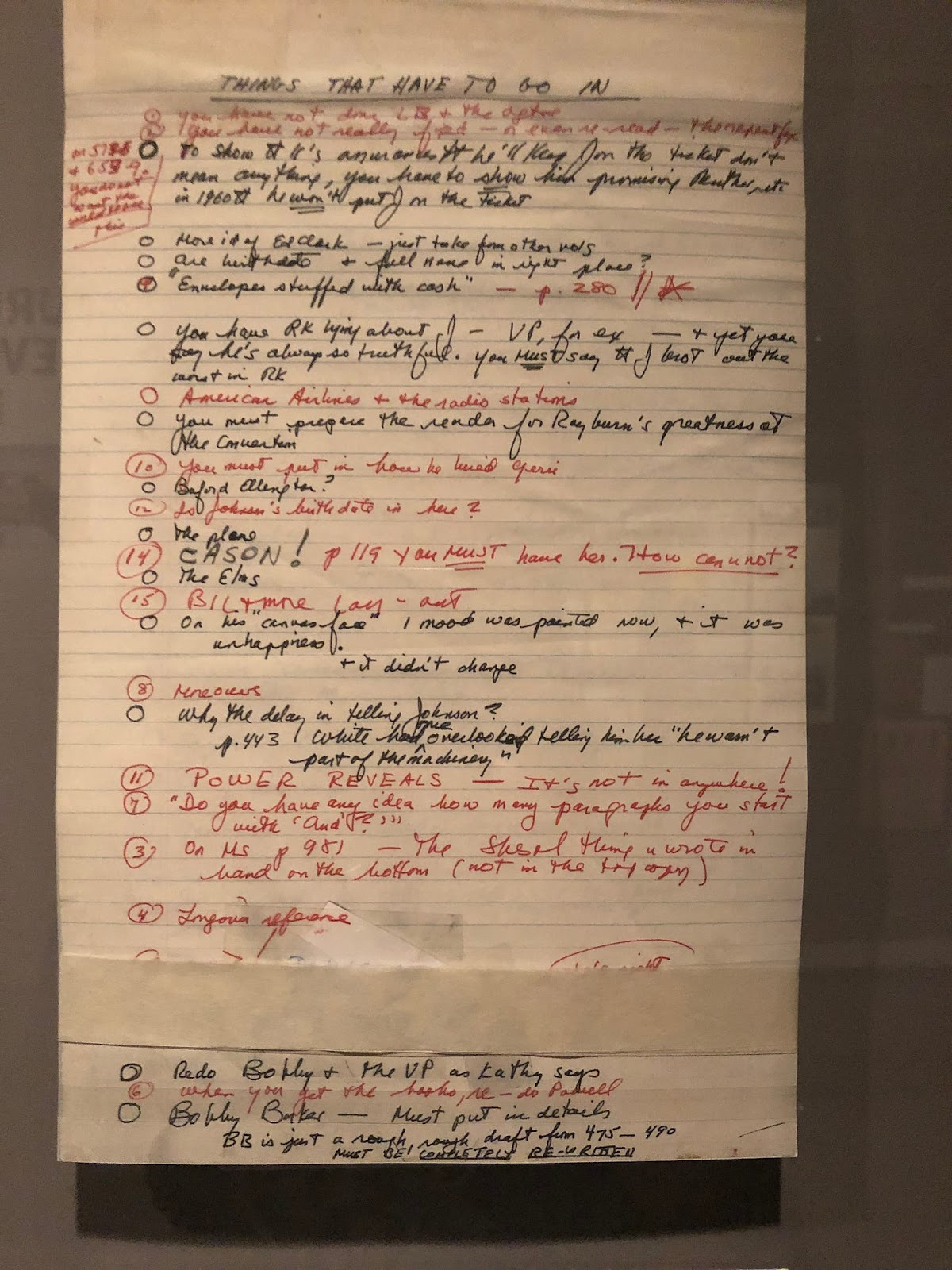

Once Caro has an entire draft, he creates lengthy to-do lists for himself. One in particular, focused on “things that have to go in,” reads like a list of reminders and self-admonishments for his writing process.

Source: New-York Historical SocietyI especially love the following items on his list:

7) “Do you have any idea how many paragraphs you start with ‘and’?”

11) POWER REVEALS—It’s not in anywhere!

Of course, #11 is the subtext of Caro’s work—power doesn’t shape a person; it reveals the person. And then there’s #14, a great example of how Caro talks to himself (and keeps track of the location of important data).

14) CASON! P119 You MUST have her. How can you not?

I assume the “Cason” Caro refers to is Betty Cason Hickman, who was in the room (taking notes) when Kennedy talked with Johnson about the vice presidency.

Notes to self, scattered around the office

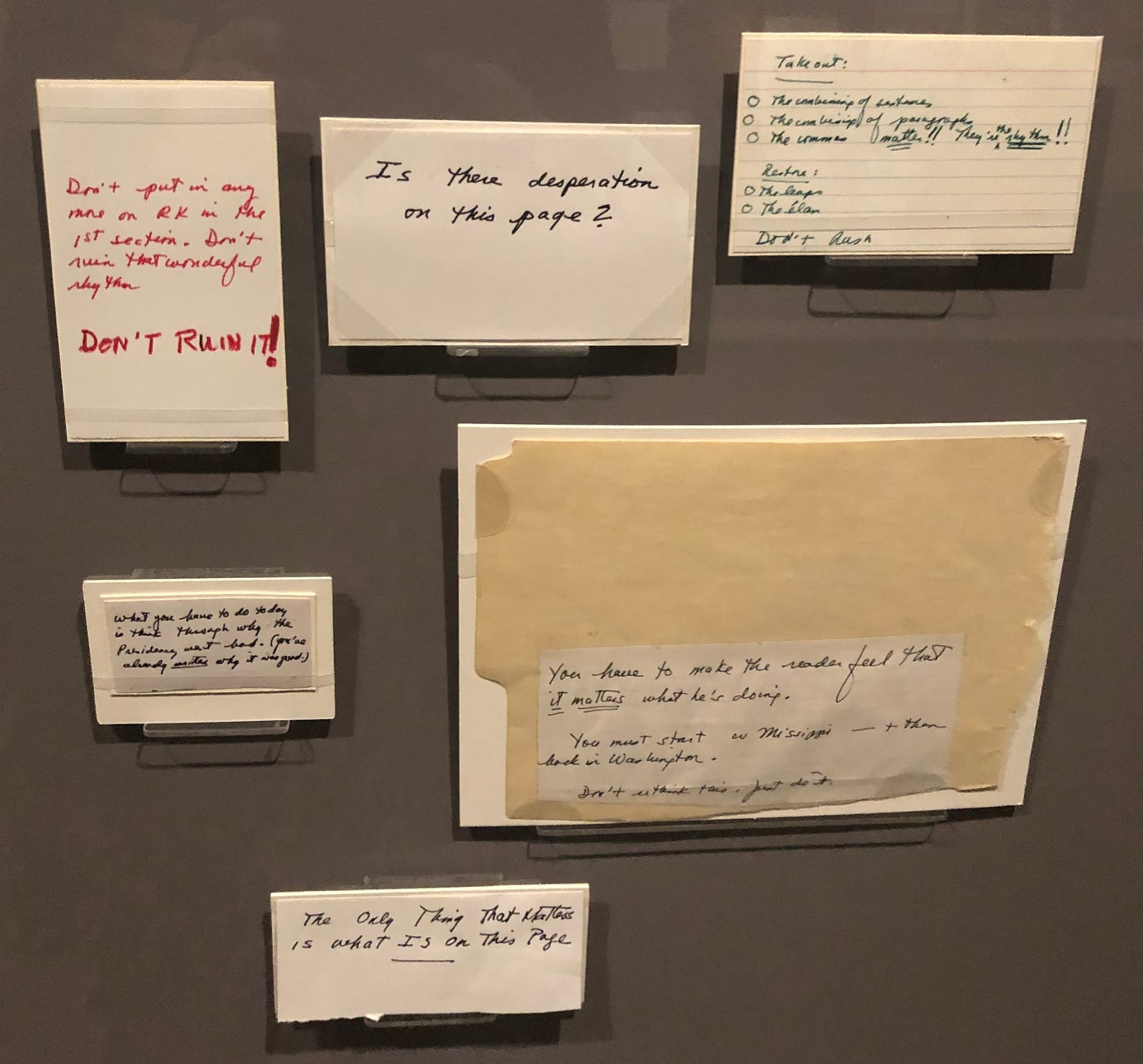

As we’ve explored, Caro had to juggle—and retain—an endless stream of information. To make sure he didn’t lose sight of the bigger picture, he wrote the best reminders to himself.

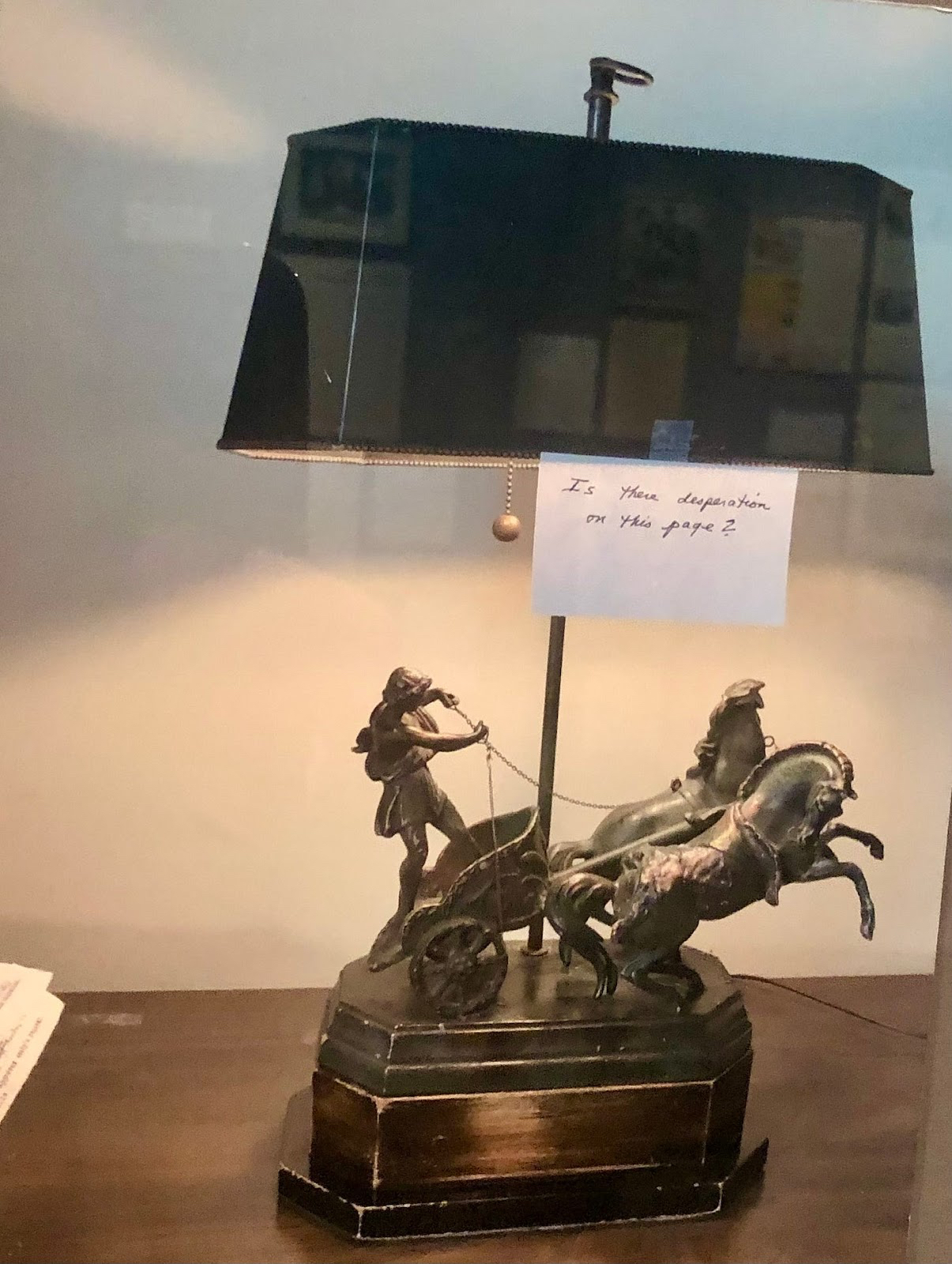

Source: New-York Historical SocietyCheck out the note attached to Caro’s desk lamp: “Is there desperation on the page?” As he explained in an interview, that’s a card he left for himself while working on a difficult chapter of LBJ’s life, where the budding politician fell far behind in the polls for the Senate election.

“He’s desperate, right?...I wanted to show his desperation,” Caro explained to the Paris Review. “I thought, ‘You have the scenes, but it’s your job to make the reader feel [it]. How do you do that?’” That goal was his north star while writing that chapter, so he left the reminder somewhere he’d see it regularly.

Other notes from Caro included reminders of what to cut from a draft, what to put into a draft, and how the reader ought to feel when reading a particular section.

Don’t put in any more on RK in the 1st section. Don’t ruin that wonderful rhythm. DON’T RUIN IT!

And, my personal favorite:

The only thing that matters is what IS on this page

Source: New-York Historical SocietyA note on Ina, Caro’s wife

I loved the Caro exhibit at the New-York Historical Society, but as a researcher, I’m left wanting more. It drives me crazy when I see a notebook behind glass and can’t turn the pages.

In particular, I want to know more about Ina, Caro’s wife. The two worked together on all of his books—she was one of the few people he trusted to help him with his research and documentation. While Robert Caro gives ample credit to Ina in his book Working, she is mostly absent from this exhibit.

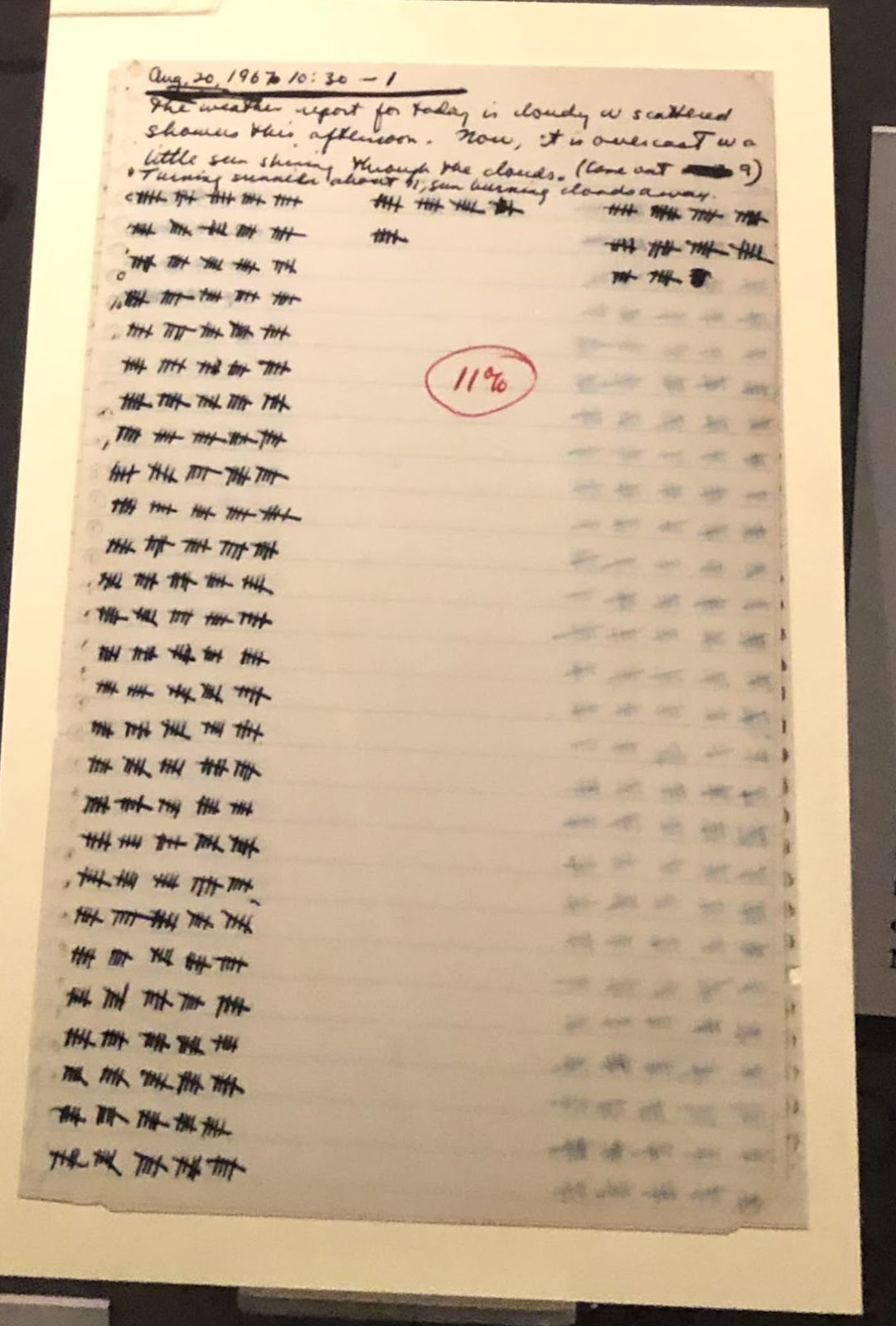

There are a few small exceptions, like a research note for The Power Broker below. It shows a tally of visitors to Jones Beach by race. In August 1969, the Caros sat in the parking lot together for a few hours to count attendees by hand, gathering evidence of the long-term impact of Robert Moses’s policies on Black and Latino New Yorkers. By curtailing public transit efforts, Moses was indeed successful in keeping people of color away from this particular park.

Source: New-York Historical Society

I contacted the New-York Historical Society to ask about Ina and learned that more of her notes are probably in the exhibit, but it’s very difficult to tell who was writing what. The NYHS is still cataloging the collection—Caro donated all his papers to them—and they should be available for research by the spring.

Jillian Hess is an English professor at the City University of New York (CUNY) and the author of How Romantics and Victorians Organized Information. You can learn more about the world's best note-takers by subscribing to her newsletter, where this piece was originally published.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

The article talks very little about Note Taking Lesssons. Much more about outlining, to-do's, and research.

Still, an interesting article.

This was a strong insight into the process Caro uses, and a reminder that to be as clear as possible on a subject, he must delve as deeply as he can.

Excellent information, well researched, and well presented. Much appreciated.