Elon Musk’s mind works a little differently than the average person. When he once found himself stuck in bumper-to-bumper LA traffic, he didn’t start cursing other drivers or fever-dreaming the opening dance number in the movie La La Land. He didn’t even turn to the more commonplace fantasy of sprouting wings and soaring away from the gridlock.

Instead, Musk channeled his inner groundhog and thought down. Namely, he wondered why valuable real estate above ground had to be packed with cars when there were hundreds of meters available for development below the Earth’s crust.

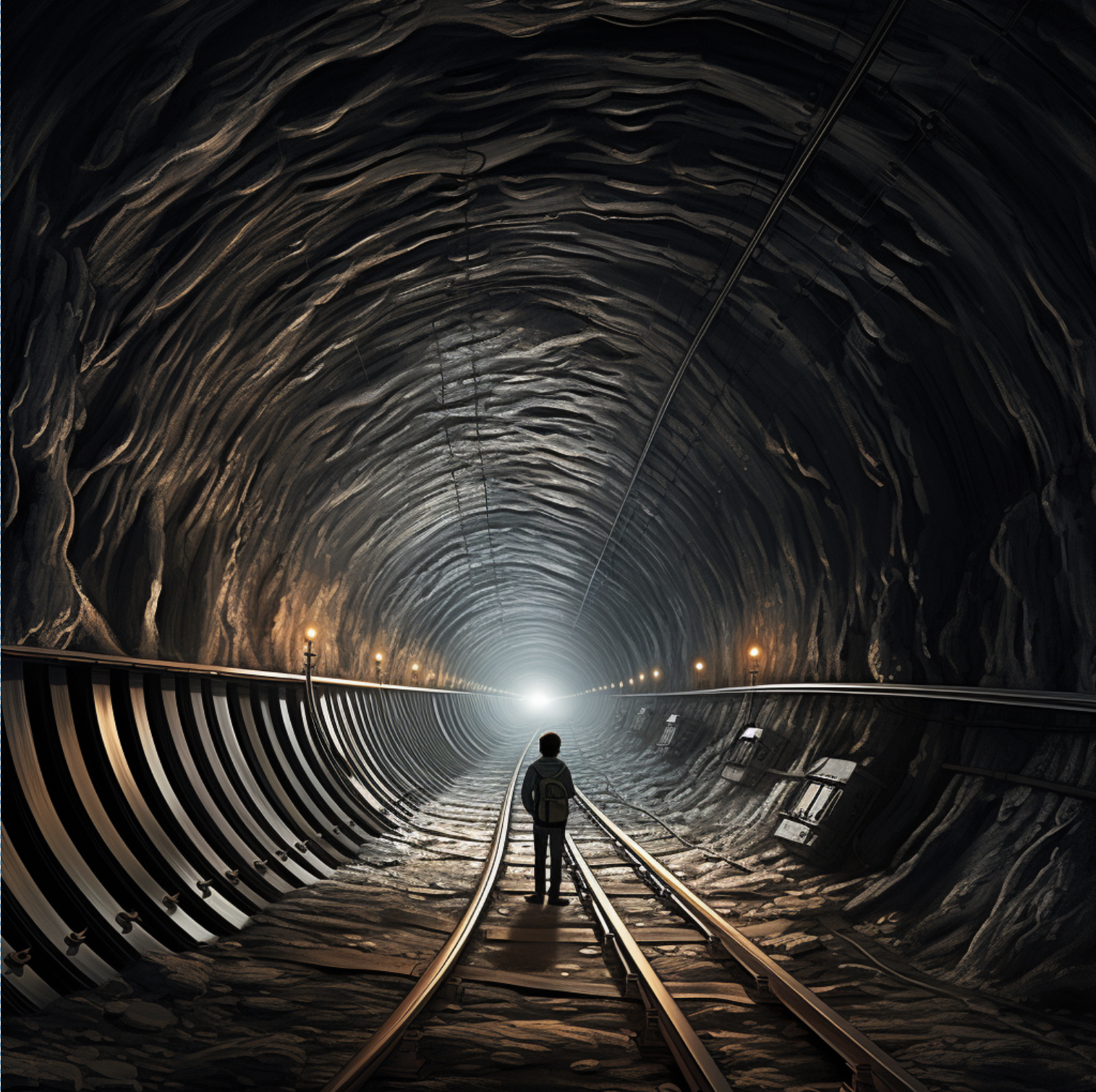

Humanity is no stranger to digging down for its transportation infrastructure. Much of the globe’s public transit was built underground, criss-crossing under urban metropolises. So why hasn’t anyone built freeways for cars like that?

This train of thought ultimately culminated in Musk’s creation of The Boring Company—tunnel boring, that is. On the surface (heh), it’s not exactly the sexiest topic, so it doesn’t get much airtime in the media. But advancements in tunnel boring could transform our infrastructure, allowing us much-needed room for human population growth—and help ameliorate issues from increasingly random weather patterns in an era of climate change.

It’s high time we stop thinking about our civilization in two-dimensional terms—existing on the surface of the Earth—and begin thinking in three dimensions. There’s a lot of low-hanging fruit for investment in TBM, or tunnel boring machines. Let’s get into the evolution of the industry and the current opportunities for disruption.

The big American tunneling slump

The rules of structural engineering assert that there are limits to how tall buildings can get. There are no such limits when we build in the other direction—down. The Burj Khalifa, the tallest building on Earth, stands at around 2,700 feet tall. One of the deepest holes ever dug, the Kola Superdeep Borehole (a scientific drilling experiment carried out by the Soviet Union in the 1970s), is over 15 Burj Khalifas in depth.

Large, powerful boring machines capable of producing underground structures have been available in their modern form since the seventies. Unfortunately, that was also the last time the tunneling industry saw any significant innovations.

Since then, the costs of digging and building underground have skyrocketed—particularly in the United States, where laying down just one mile of underground tunnel can cost upwards of a $1 billion, the highest price tag in the world. As our need for more sophisticated underground construction has grown, the costs of doing so have ballooned in tandem.

A simple extension to the Manhattan subway system resulted in the most expensive subway project in the world. It ran up a bill of $2.5 billion per mile, five times more than what it would’ve cost to build the same thing in Paris.

Or take the nightmarish history of the “Big Dig.” This project, which aimed to build new underwater tunnels connecting the banks of Boston, became the most expensive highway project in the United States. An initial budget of $2.8 billion ballooned to $22 billion, a cost that probably won’t be fully paid until 2038. Construction for the Big Dig began in 1991 and was scheduled to be completed by 1998. Instead, the project was finally completed on December 31, 2007—a whole decade behind schedule.

Although cost and scheduling issues have plagued American infrastructure projects in recent decades, the U.S. didn’t seem to have much of a problem building its extensive system of highways and corresponding tunnels during the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, the list of impressive and complex tunnels built across America is extensive, even if most of those tunnels were constructed half a century ago. It is only lately that building new infrastructure in the U.S. has become so difficult.

This isn’t the case universally. Over the course of 2023, other countries have eagerly embarked on all kinds of new underground transportation projects. For example, London unveiled its Crossrail plan, which will expand the city’s rail capacity by 10% and carry 200 million people a year. (Though it’s worth noting that this project, too, was criticized for delayed construction and a higher-than-expected budget.)

This tunnel was actually constructed beneath another London tunnel—the Mail Rail. For 76 years, between 1927 and 2003, the UK Post Office delivered mail to customers using a network of underground tunnels and rail carts. Since 2003, that network has become an underground laboratory for Cambridge engineering students studying the effects that building another tunnel beneath the Mail Rail line would have on the original tunnel’s structural soundness. So far, so good, it seems. In addition to rail, in 2026 Great Britain will embark on building its longest road tunnel yet: the Lower Thames Crossing.

All across Europe and Asia, tunneling projects to expand roadways, replace leaky old utility pipes, or redirect flows of water are making headway. All of this progress makes the question of America’s difficulty in building new underground constructions even more puzzling. What gives?

A brief history of tunneling

Underground construction is actually an ancient practice. As far as we know, the first tunnel ever built was the Euphrates Tunnel in Mesopotamia. This was likely constructed sometime around 2170 BC to connect the two sides of Babylon beneath the Euphrates River.

Although the tunnel has never been found, there are accounts of the tunnel in the writings of the ancient Greek historian Diodorus. Diodorus wrote his account much later, in 50 BC, but he described with great detail the means by which the Babylonians dammed the river, dug the tunnel, lined its walls with brick and bitumen to secure and waterproof it, then covered it up to restore the flow of the river.

Another sub-sea tunnel of such ambition was not built until many thousands of years later, but many impressive underground structures were still embarked upon in the intervening period. Take the Valley of the Kings, a massive system of underground tombs consisting of hundreds of chambers built amid limestone, shale, and chalk used to bury the pharaohs and high-ranking officials of ancient Egypt. Or take the ancient Persians, who built tunnels over 2,700 years ago, many of which are still in use today. Romans built tunnels, too, to divert rivers and allow passage through treacherous terrain.

What is perhaps most amazing about all these passages and constructions is that they were built without any formal knowledge of the advanced math or physics we use in construction today. All that was required was a combination of rigorous practicality and intuition, passed down through time, from master to apprentice.

Their solutions to hard problems, like carving through rock, were ingenious. At times they used the technique of fire-quenching, which heats the rock and rapidly cools it with cold water to make it crack. Of course, all of these constructions were built by armies of thousands of workers who chiseled away at stone for days on end.

The fall of the Roman Empire put an end to massive underground construction. It was not possible to organize the extraordinary labor force to take on such an effort anymore, and it would take centuries for tunneling to become economical again.

The invention of gunpowder in 1627, and the rise of explosives more generally, made it possible to unleash a massive amount of force very quickly. Hard rock didn’t need to be fire-quenched or chiseled away a few chips at a time anymore—it could just be blasted to bits. Simply by drilling a small opening in a rock, packing it tightly with a lot of gunpowder, attaching a fuse, and lighting it, massive amounts of rock could be removed, greatly accelerating the tunneling process.

After the invention of gunpowder and dynamite, throughout the 1800s, Europe became obsessed with blasting away mountains and rock faces to carve new train paths through the Alps, and through the rocky regions of England, Switzerland, and elsewhere.

However, even after clearing through rock became easier, there were still many challenges that came with tunnel construction. Four thousand years after the Babylonians supposedly built a half-mile-long tunnel beneath the Euphrates, the English were having a great deal of trouble doing something similar in the mid-1800s. At that time, there was a growing desire to create a tunnel to connect both sides of London beneath the Thames River. Numerous attempts at doing so ended in failure. The issue stemmed from the fact that engineers would run into soft clay and quicksand, which kept flooding out or collapsing the excavation attempts being made.

In 1823, however, an intrepid engineer named Marc Brunel produced a new plan to tunnel beneath the Thames River using a new tunneling system he patented called a “tunneling shield.” The idea was to bore a large hole in one bank of the Thames that would reach the intended depth of the tunnel. Inside the hole, a multi-level structure would be built, facing the wall to be excavated, with compartments created for numerous workers who would carve out the wall face manually.

The excavated dirt would then be removed via the shaft, and while the tunnel bored further beneath the Thames, additional workers would secure the structure of the tunnel by laying brick around it in the rear. This way, the tunnel could be dug and structurally secured simultaneously. The digging was slow because it was manual, but it made tunneling under a river possible. The Thames River Tunnel took 18 years to complete and was finally opened in 1843.

Source: LondonistTunnel-mania subsequently consumed Europe. In 1863, London began building the world’s first underground metro. Much of it was constructed using another tunneling technique, called cut-and-cover. With this technique, an open trench was dug spanning the length of the metro line, structural supports were added, and then the tunnel was covered up.

This open-air technique was much preferred to the fully underground digging. The latter method had very poor circulation combined with the risk of leakage of noxious and flammable fumes, which blighted much of the Thames tunnel construction process.

While much of Europe and New York were in the process of digging up their cities to install new underground transportation, they also took the opportunity to install subterranean sewage systems alongside the new subterranean transit system. As a result, following the construction of most modern subways across London, Paris, Budapest, and New York, many of today’s modern sewage systems were also built.

Source: The History PressAs tunnel construction continued, attempts were made to automate boring at the face of the tunnel using pneumatic drills. The first such machine was Henri Maus’s boring machine, created in 1848. This was heavily inspired by Brunel’s shielding structure, but instead of placing men at the tunnel face, Maus replaced them with rows and rows of drills.

Tunnel boring machines were expensive to produce, and ultimately were not capable of cutting through rock. Remarkably, it would take another 100 years for this to become possible.

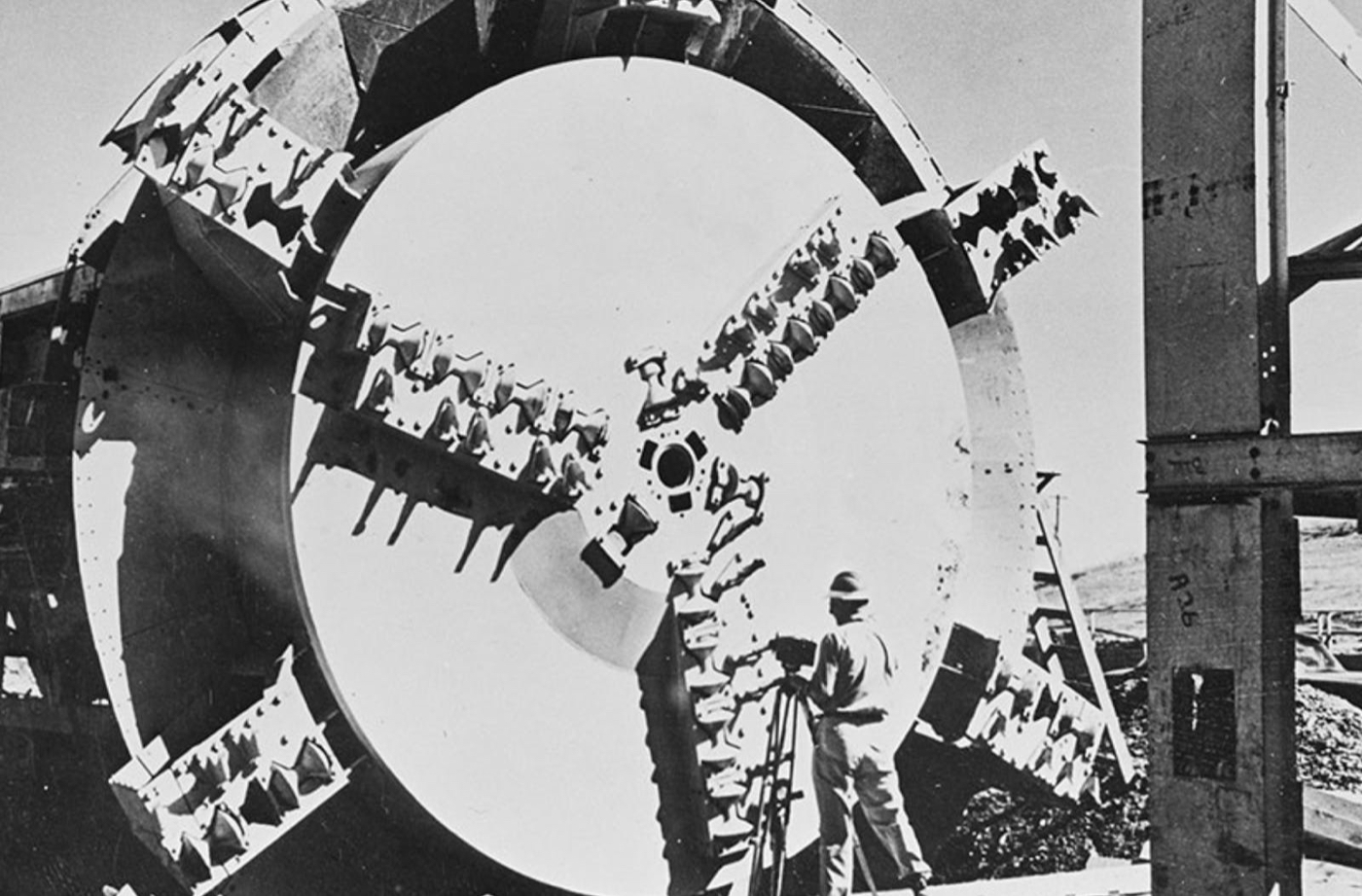

In 1952, an American engineer James Robbins was the first to design a tunnel boring machine that used serrated components called drag bits alongside sharp disc cutters on the machine’s cutter head. The components worked in unison, such that while the drag bits grooved the rock, the cutters could break off parts of the stone. The machine ended up being used to build the Oahe Dam in South Dakota. Since then, Robbins started one of the most prominent boring companies still producing tunnel boring machines today.

Source: Robbins TBMHow tunnel boring works

There’s not a lot that separates the tunnel boring machines of today from the one designed by Robbins in the fifties. While different technical adjustments were made to the cutterhead allowing it to bore through different types of soil, the overall operation of the boring machines remains unchanged. Let’s break down exactly what that operation looks like:

1. Surveying

Before any digging begins, teams must first get a firm sense of what they will be boring through. The type of material beneath the earth will not only determine whether a tunnel may be dug, but also what kind of tunnel boring machine (TBM) will be needed, if one will be needed at all.

One of the most difficult things about underground construction is never being 100% certain of what you’ll find. That’s why de-risking with extensive testing and surveying ahead of time is crucial. Geotechnical surveys to assess the composition of the rock or soil are conducted by drilling boreholes to extract and analyze soil samples. Ground-penetrating radar is also used to produce images of the subsurface and detect unexpected voids, caverns, or other structural qualities.

If digging through soft or granular soil, slurry shield TBMs— which pump a thickening agent called a slurry ahead of the cutter to help maintain the structure of the borehole as it moves through the watery and sandy soil—may be used. Clay-based or silt-like soils might use an Earth Pressure Balance TBM, which tries to balance pressure from the earth with pressure from the boring machine as it digs. There are also Mixshield TBMs that handle heterogeneous ground and Hard Rock TBMs that handle very tough rock formations.

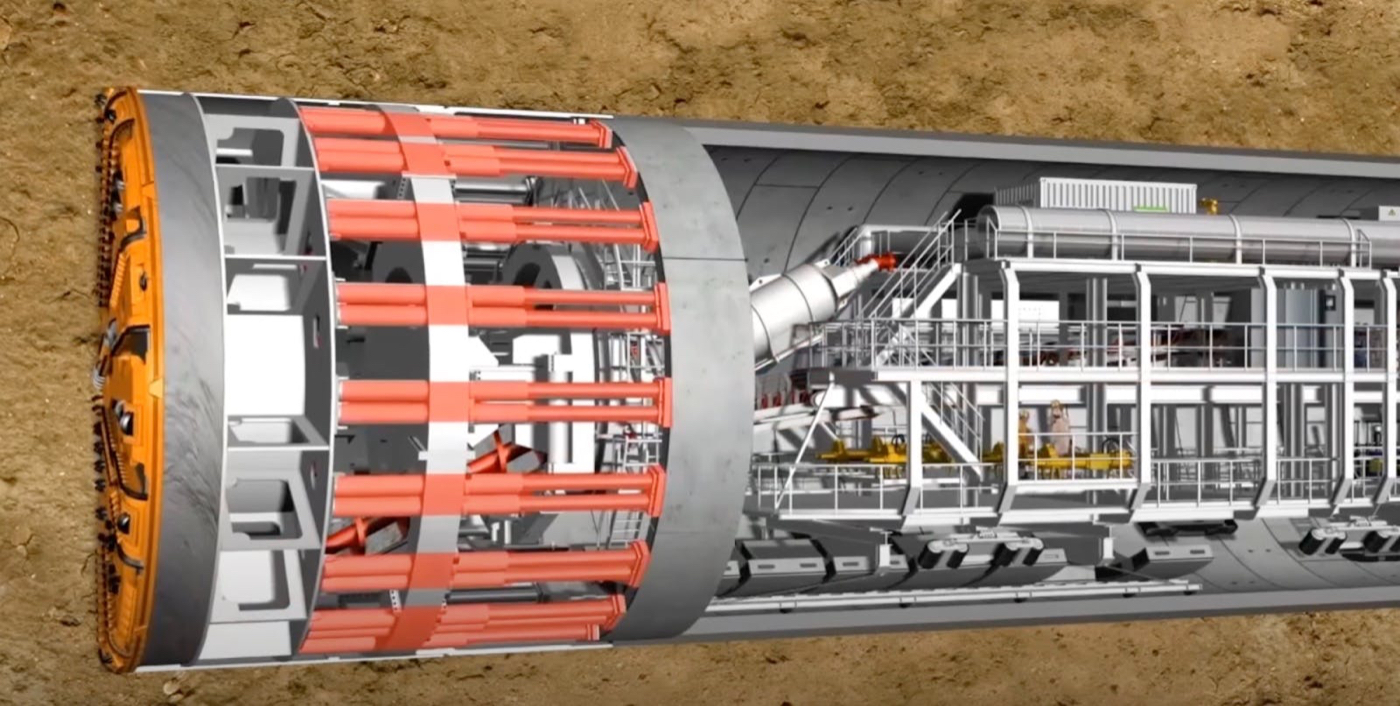

2. Excavation

Once the surveying is complete, TBMs are usually custom-built for the specific dig project. In most cases, they’re made and tested at a factory before being disassembled and shipped to the project site where they are reconstructed.

After this, an access shaft is dug, into which the TBM is carefully lowered. The most important part to get right at this stage is correct orientation of the TBM. Different tools from inclinometers to even GPS are used to ensure TBMs are oriented correctly in the digging process. Once in place, the cutting face will begin rotating and carving through soil. The TBM has extending hydraulic arms that push on the cutter head with a pressure of 400 bar, roughly 400 times the atmospheric pressure at sea level.

Source: Herrenknecht AGAs soil is excavated, it falls off the face of the cutter and is collected by a series of conveyor belts that carry it out of the tunnel. The entire structure of the TBM is held inside of a giant cylindrical shell that ensures the structural integrity of the front of the tunnel as the cutterhead carves the path ahead.

Source: Tunneling Online3. Structural lining

Also onboard the TBM are precisely shaped lining segments molded out of concrete on site. As the TBM advances further in the tunnel, the lining segments are picked up by an erector inside of the machine and installed inside its cylindrical shell. The segments are interlocked, creating a sturdy and durable structure that distributes the load and pressure from the surrounding soil. Then, the hydraulic thrusters push off against the newly installed concrete segments to advance forward, leaving a completed concrete tunnel ring behind it.

Though the TBM works faster than an army of men with pickaxes, it still doesn’t work very fast. Modern TBMs advance at a rate of 15 meters per day on average, which is an improvement over Brunel’s shield tunneling method that advanced at an average of four inches per day, but is still some 14 times slower than a snail’s pace.

A further inefficiency is the fact that TBMs stop digging while the structural linings are being installed along the sides. That work ceases to ensure that the structural linings are secure before moving forward, but it also means that TBMs are not digging for much of the time they are underground.

Though there are many complex issues plaguing the construction of tunnels today, these are some of the lowest-hanging fruit when it comes to improving TBM performance and cost efficiency.

The Boring Company is not so boring after all

Enter Elon Musk. After suffering the hell that is Los Angeles rush hour, he began wondering why travel infrastructure in the city wasn’t underground. He learned that boring machines were the problem because they were slow at their job and expensive to build and operate. So in 2017, he started The Boring Company.

The main objectives of The Boring Company were twofold: to increase the power and speed of traditional boring machines, and to make the process of lining the tunnel happen simultaneously as the machine digs.

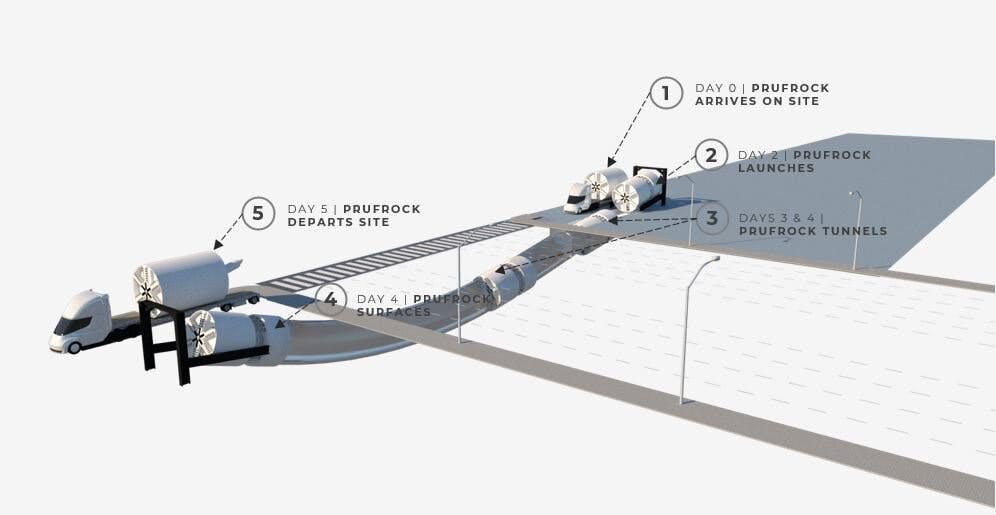

The company’s boring machines, the Prufrock models, are already capable of digging faster than traditional TBMs. The Prufrock-2 digs up to a mile per week. Its successor, the Prufrock-3, is expected to dig at a rate of seven miles per day. Another innovation of the Prufrock is “porpoising”—rather than digging a hole and lowering the TBM into it before it can get to work, the Prufrock can just bore straight into the earth to the desired depth from the surface. Then, once it’s done digging the tunnel, it resurfaces and can be collected.

Source: The Boring CompanyMusk loves the concept of reusability, and tunnel construction is another sector (in addition to space) where reusability could massively decrease costs. In many projects, it is so costly to remove the TBM from its tunnel that many companies just leave it below ground once the tunnel is constructed. With porpoising, The Boring Company is making TBMs reusable, lowering the cost of digging.

In short, The Boring Company isn’t completely re-imagining tunnel digging, just trimming the fat by lowering costs while also perfecting existing techniques to allow for faster digging.

Other innovative companies in underground construction

There are a few other endeavors attempting to rethink the underground construction process from the bottom up. One such company is hyperTunnel, a British tunneling startup founded in 2018.

HyperTunnel envisions a fully autonomous system composed of swarming robots that can drill the tunnel outline and set its external structure using 3D-printed material—eliminating the need for a large boring machine that pulverizes the ground. Once this tunnel structure is set, the earth beneath it will simply break off and be removed.

The goal, however, is that this technology could be used to build much more complicated underground structures than what is currently feasible through boring machines alone. The company is working on prototyping this technique, but it seems likely it will only work for softer soils.

Digging through hard rock is still a big issue for tunneling, and many kinds of hard rock—like granite and quartzite—are challenging even for TBMs to bore through. Companies like Earth Grid and Petra are trying a variety of techniques, from plasma torches to superheated fluids that can crack tough rock.

The future of digging

The clock is ticking on the need for better tunneling technology. The planet is starting to feel the effects of climate change, and atypical weather patterns are wreaking havoc on our existing infrastructure. Freak weather incidents—like the recent hurricane-fire in Maui—damage above-ground utilities like power lines.

As Jeremy Hammond, the co-CEO of HyperTunnel, pointed out:

“The global urban population is expected to more than double by 2050, highlighting a critical need for more transportation solutions for people, vehicles, water and sewage. As cities expand, and their existing spaces and networks are placed under unprecedented levels of pressure, it’s clear that more infrastructure must go underground.”

Whether it’s three-dimensional highway structures, or easily accessible and well-organized utility tunnels, underground building has tremendous promise. It’s woefully under-explored—because we’re not that good at it!—but with all the re-ignited interest in boring, hopefully that will change soon enough.

Anna-Sofia Lesiv is a writer at venture capital firm Contrary, where she originally published this piece. She graduated from Stanford with a degree in economics and has worked at Bridgewater, Founders Fund, and 8VC.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

ENvironmental concerns? The bit about UK was interesting - I am from there and Crossrail has destroyed vast pasts of teh country and has recently been halted because of its cost. I think there could have been a little more criticality would have made this more robust.

I appreciate learning about the basic processes of boring so that we can better understand the possibilities and current limitations of this technology. This article brought me back to a quote I've been thinking about a lot: "These are engineering problems. And we are engineers." If we can isolate obstacles, then we can propose solutions to those obstacles, instead of writing off an idea entirely because it contains obstacles.

I recently travelled to Europe for the first time and everywhere I went, I was so impressed by the robust public transportation systems, a lot of which is underground. It made me question how we could possibly get infrastructure like that in Western Canada, where our cities have been designed, built, and expanded to accommodate more and more cars. Perhaps underground boring is part of the answer.

"He learned that boring machines were the problem because they were slow at their job and expensive to build and operate" That's not at all the problem. This article is informative with the historic part and totally garbage considering taking every word from our beloved Space Karen for granted whilst Elmo showed us he was lying in every regard. The Article doesn't even mention the ridiculously ineffecient and expensive tunnel in Las Vegas, that the Boring Company Build where a single Bus traveling the normal roads is more effective by a margin.

I am so tired of articles starting off about and going into anything about Elon Musk

Watch other technologies around us and try them to better another,...like how about the DEW applied as a 'drill bit' . Laser cutting can also cut the round shape first for a meter or so and then that meter thick 'disc' can be shatterred with high frequencies..?..