In startups, speed reduces risk.

In many ways, this is deeply, deeply counterintuitive. It goes against the physical intuition we've all acquired from youthful scraped knees and twisted ankles. It goes against the conventional wisdom drummed into us at school. It goes against the operating principles beloved of large organizations—diversify your efforts, hedge all risks, operate redundantly, work to a cadence.

These principles don’t apply to early-stage companies. They’re not just irrelevant, they’re anti-patterns that will actively hurt founders’ efforts. Speed is the single best way to de-risk a startup. Many people in tech know this in theory, but truly believing and acting on it is much harder.

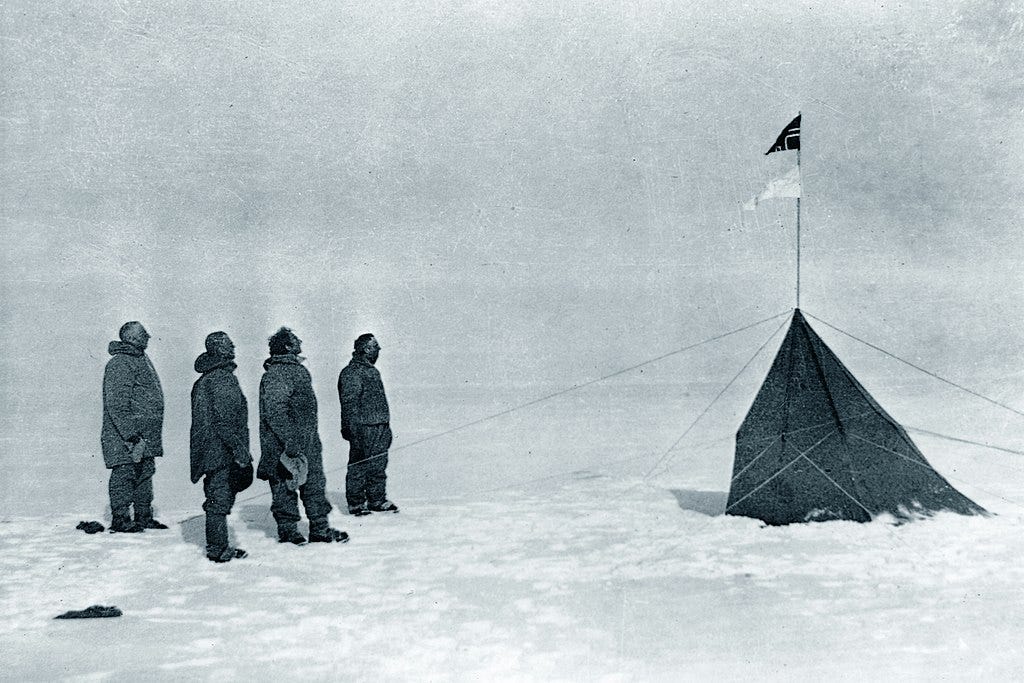

To help remind you of this lesson, let’s peek into the annals of history—namely, the race to the South Pole in the early 1900’s. It’s a tale of two polar expedition parties, one focused on speed and the other on caution. As you might expect, one story ends in victory, and the other in tragedy. Consider it an apt analogy.

The worst journey in the world

In 1911, two different parties set out to reach the South Pole. One was led by British Royal Navy officer Robert Falcon Scott. He believed there was safety in numbers: that a large, slow-moving convoy faced fewer risks than a small and agile team.

He thought the success of such a convoy depended on perfect adherence to complex plans, often written down weeks or months in advance. He enforced strict Naval discipline and a rigid hierarchy, to ensure there were no deviations from these plans.

When conditions on the ground belied his assumptions, he refused to change. When things went wrong, as they inevitably did, Scott struggled to course correct.

It didn’t help that Scott’s party had taken on many scientific goals for their journey, beyond being first to the South Pole. They tried to study and document various environmental factors. They hauled pounds of specimens, like rocks, extracted from the landscape. They experimented with new transport approaches, like ponies and motorized sledges (a type of sleigh).

In short, they did too much and it slowed them down.

As things went wrong, Scott’s team had to contend with constant gnawing hunger, cold and thirst, going on short rations and running out of fuel while performing prodigious amounts of work. His party suffered terribly from deficiency disease, injuries (one person’s leg and another’s hand rendered them unable to work or even walk sometimes), snow blindness, frostbite, gangrene and more.

In the end, Scott and his polar party paid the price for his rigidity. The four men who made the final leg of the trek all died, despite a rescue attempt staged by those who remained at base camp.

Caption: Man-hauling in the Antarctic

Shaving down the skis, and other details of success

In striking contrast, Scott's great rival—the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen—succeeded with comparative ease (mere weeks apart!). Every aspect of his strategy—equipment, transport, and personnel—was optimized for speed.

Over the winter before the polar dash, Amundsen's team laboriously reviewed every single piece of gear they’d carry, with the sole goal of saving time. They shaved down the skis to save a few ounces of weight. They unpacked their bulk rations and repacked it into daily allowances. They sewed two tents together to halve their setup time. They designed storage canisters that could be opened without unlashing them from the sledges.

Amundsen traveled with a small group, knowing they’d travel lighter and move faster. To make up for lack of numbers, everyone picked had multiple specialties. Olav Bjaaland was a national ski champion who was also a highly skilled carpenter. Helmer Hanssen was both a superb navigator and experienced dog handler. Sverre Hassel was a qualified ship's mate, navigator, sail-maker and leather-worker.

Most importantly, having assembled this team Amundsen gave them wide discretion to act independently. Again, this was in the service of speed, but it also helped with adaptability to unforeseen circumstances.

While Scott's 12-man summit party laboriously dragged 1000 kg of food and supplies up a 10,000 ft glacier on sticky wooden sledges, Amundsen's party used skis and dogsleds and didn't have to man-haul once.

Lastly, Amundsen focused them on a single goal: to get to the Pole and back as quickly as possible. He was happy to take tactical risks to serve this strategy. For instance, both his base and his route were on uncharted (and hence dangerous) territory. They were chosen because they shortened his journey by hundreds of miles; he correctly judged that this was the lesser risk.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!