I went to see Seth Godin to talk about organizing. And I was nervous.

To get to his office I took the train from Manhattan to Westchester on a sunny February day.

I sat by the window. I watched the white caps on the Hudson as we made our way north. I put my head on the window and closed my eyes.

The night before I had stayed up late to put the finishing touches on the usual prep email I send to guests. I had read every article he’d written about productivity and organization. I had listened to previous podcasts, and reread a few of his books.

The email was lengthy, and each question cited at least a few of his blog posts — I wanted him to know that I’d done my research, and that I wanted to go deep.

I fired it off at 10 PM the night before, exhausted but feeling a little proud and very ready to get on the train to interview him the next day.

I woke up early the next morning and read his response to the questions I had crafted:

“I'm happy to try, and I'm looking forward to seeing you. But I think the biggest takeaway for your readers will be how little my life reflects the questions you want to ask me.”

Uh oh.

. . .

Seth Godin could work in a skyscraper. Instead, he works in a converted apartment in a small town in upstate New York.

Seth Godin could fill his office with flashy paintings, and expensive furniture. Instead, his office is filled with books, and papers, and posters blossoming in every color from every corner of every room. His workspace is his own mind turned inside out and made manifest as interior decoration.

Seth Godin could have a gigantic staff to order around, but instead he employs a small crew of friendly people who he treats like family. He makes them lunch every day. Often dal.

When I show up he’s on a Zoom call with students from his latest course, Creative Workshop.

“Mr. Shipper!” he booms as he bounds out of the room. He’s wearing a blue dress shirt, and a loose pink and yellow tie, the pink and yellow twisting together like a soft-serve swirl.

We go into his office and shut the door. He’s got this underlying energy that is at times bouncy, friendly, and almost goofy. But at others it is taut, focused, and intensely concentrated.

We sit down to examine one question: is the whole thesis of this newsletter wrong?

. . .

My usual tactic for dealing with nerves is to name them. So I do.

“I'm a little bit nervous to do this interview because I don't know if you believe in the thesis of Superorganizers,” I say.

“You shouldn't be nervous,” he says. “But I don't. I believe it's useful to have the conversation, but I don't worship at the altar of organization.”

“I want to explore that,” I say.

Then I plug in my microphone and hit record.

Usually, I use only one. But for this interview I plug in two — just in case. I don’t want to miss anything.

Seth introduces himself

I’m Seth Godin. I’m an author, speaker, and entrepreneur. I’ve published 139 books including This Is Marketing, Purple Cow, and Tribes. I’ve written a blog post every day for decades, and I run workshops like altMBA and the Creative’s Workshop.

How Seth thinks about organization

I’ll tell you a story about how I think about organizing.

I went to the engineering school at Tufts for college. One of the classes I took there was an invention design class.

Our first assignment was to build a case for all the freshmen to organize their tools in.

Back then, every freshman was given about 30 tools to help them do their work — things like a protractor, a mechanical pencil, and a fancy ruler. And we had to build a case for them.

The freshmen would use the case for two weeks, and then we would get a report back about whether it was useful.

Everyone else in the class spent hours and hours building these ornate, beautiful cases that had custom foam inserts that were cut out to organize just the right tool in just the right place. So you’d have a space exactly cut out for your protractor, and a space exactly cut out for your ruler. And everything would be neat and tidy and organized.

But I didn’t do that. What I did was I went to Harvard Square, got a paint box that artists use, and then put a piece of foam on the top of the box and a piece of foam on the bottom of the box.

The way it worked was you just throw your tools in the box and then you close it. Your tools wouldn’t move because the two pieces of foam held them in place, and when you opened the box again your tools would be just where you put them.

I worked on it for a total of seven minutes, and then I handed it in. The students who used it loved it. They said it worked great.

But my professor gave me an F on the project. So I went to him and said, “Why did you give me an F?”

He said, “Because you only worked on it for seven minutes.”

And I said, “Yeah, but it’s not an arts and crafts project. It did exactly what it was supposed to do.”

So my professor changed my grade to an A. And that’s my philosophy on organizing.

Organizing is like building a case to hold your tools. You don’t get points for making it fancy, you get points for doing the work.

Seth needs the noise to do his work

When I think about organizing I think about two things: who’s it for and what’s it for? To answer the first question: it’s for you.

To answer the second question, usually people say: it’s to lower the noise level in your own head.

And I think that definitely makes sense for some people.

But lowering the noise level is just not something I need. I need the noise. If there isn’t noise, I make some.

Maybe it’s because I grew up with undiagnosed ADD — but I need more froth and motion than a highly evolved organization system would give me. I don’t feel like the time I spend archiving, organizing, and alphabetizing things is really helping me with my work.

There are definitely certain moments when I will feel overwhelmed by the amount of things that are going on, and that will shut down my creativity. It feels like I can’t put another log in the fire because it’s already too hot.

But in those moments I choose not to be overwhelmed by it. I choose to use it as fuel.

Seth on being productive

I like to be productive.

I've published 139 books. I did a book a month for 10 years as a book packager. I like shipping things, and shipping consistently has helped put me at the forefront of a number of big shifts in technology over the past few decades.

But being productive and being organized are not always the same thing. The trap with organizing is that it can sometimes be an excuse not to ship things.

I will often run into people who will say they need the right scenario to do their work. If they only had a better camera, or the right word processor, or a better organizational system they would begin doing the work.

But you don’t need the perfect setup to do the work.

For example, I’ve written five of my books completely on airplanes.

That is not what someone expects when they ask about my system for writing productivity. They imagine that a writer will go to a library — a place where you’re supposed to be quiet and nothing is supposed to be in front of you and the environment is perfectly set up to work. They don’t imagine me sitting in the middle seat on an airplane typing on my laptop.

But I’ve found that you can’t wait for the perfect setup, because that will never arrive. It’s too often an excuse not to ship.

I’m not saying that everyone who organizes uses it as an excuse. But some do. And it’s something to watch out for.

Don’t ask: am I organized enough? Instead, you might ask: Am I shipping work in sufficient quality and quantity to cause the changes I seek to make? If not, what’s stopping me?

How Seth makes sure to ship work that is important enough

Shipping has never been a problem for me. What has always been a problem for me is shipping work that is important enough.

This comes down to the difference between a professional and an amateur. An amateur doesn’t care about the audience; the amateur is doing it for themselves. To be a professional, you have to engage with somebody — you have to engage with an audience.

But engaging an audience is right next to being a hack. It’s a subtle line.

Being a hack is giving the client what they say they want instead of what they actually need. Because I bootstrapped my company, because I got 800 rejections in the first year, because I was on the ropes for many years, I danced on the edge of being a hack. I needed to sell stuff.

What I had to do to make sure I was doing important work was to hone my intuition and start to understand the signals better.

I ask myself, What am I doing this for? What is its purpose other than getting paid? Because if I really want to get paid, I should go to work for Goldman Sachs. As soon as you make the decision not to work at Goldman Sachs everything you're doing should be because you are trying to enable your mission, not because you are trying to make a living.

So I’m asking, What is the change I’m trying to make? And, Who’s it for and what’s it for? And then I ask things like, What’s the medium that will help it get there? Is it a blog post, or a talk? Or is it a book? What box does it fit in?

Once I’ve tried to answer those questions then I jump in. Starting a new project is like jumping into a swimming pool: you don’t accidentally get wet. You put on your bathing suit and you go into the pool.

I don’t understand the people who slowly wade into the pool.

If you want to get in the pool, get in the pool.

Paying attention to the froth

I talked about liking noise earlier. Maybe a better word for what I’m talking about is froth.

Froth is the foam on top of the thing. It’s all the stuff that’s in the corner of your eye, that’s peripheral. I think there’s great value in that stuff.

I’ve always seen things out of the corner of my eye. That’s the froth — everything happening in the periphery, in the corner of your eye. Those are the things that you get a hunch about and follow.

A good example of this is email. When it came out, most people looked at email as fax adjacent. I still remember an article from Ad Age in 1980 that listed out the CEOs that still didn’t have email addresses. It wasn’t shocking back then to think that a CEO didn’t have an email address. They would just have their secretary type a memo and then run it down the hall.

But I saw this thing — email — and it wasn’t in the center of anyone’s frame. It was all the way over there, and I chased it down deliberately because it was interesting to me.

There’s a trope out there that you should just pay attention to the thing in front of you. But that doesn’t work for me. The problem with there only being one thing in front of me is that I actually pay attention to it less.

If there’s nothing in the corner of my eye, I can’t pay attention to the thing in front of me. I need that froth around me to help me focus and keep me engaged.

For me, being around the froth actually helps me be productive.

Seth only pays attention to people who get the joke

Another thing that helps me to be productive is to pay attention only to people who get the joke.

When you make any piece of work that matters, the vast majority of people aren't going to like it. And there are several ways to get through that. One way to get through that is to sand off the edges and make it so that no one hates it. That's a bad idea. The other way to get through it is to deliberately insulate yourself from the people who don't get the joke.

For example, I haven't read an Amazon review in seven years. I haven’t read a five star review or a one star review or anything in between.

I stopped because I've never met an author who read all of their one star reviews and said, “Now I'm a better writer.”

All a one star review says is, “I'm not the kind of person that likes a book like this.” Reading a review like that doesn’t tell me anything about me. It tells me something about the reviewer.

So what I do is I surround myself with people who get the joke. And, to be clear, that doesn’t mean I don’t pay attention to people who disagree.

If someone who gets the joke, can honestly say to you, you're not achieving what you’re seeking to achieve with a piece of work, that's priceless feedback. But if someone says, “I don't like that,” Then I haven't learned anything from that.

I’ve maybe learned something about them, but I haven’t learned anything about the work.

Seth’s Wordpress setup

I switched from TypePad to Wordpress a few years ago. And that caused a bit of a crisis in the office. We were afraid that my voice was going to disappear, because the actual writing interface of TypePad triggers my blog voice.

I need my writing platform to feel like the place where I do the work. I learned that from Chip Conley. You want to have an environment that you go to for only one reason: to do the work. That’s what TypePad was for me.

But I ended up being able to make the transition to Wordpress just fine.

What you’re seeing here is all of the posts from the last couple of weeks.

When it’s time to write a post, I’ll press the compose button and type it out. Then, when it’s done, I’ll try to figure out where to stick the post in the queue.

I don’t like to have to actually push publish on these posts at 4 in the morning, so I queue them up to go out automatically.

Every night I’ll look at what posts are imminent and often will delete it because I’ll have come up with something better than that. I want people to see the best thing I have for them that day.

For every blog post people see, I write two or three that I don’t publish. The rest usually get deleted, but sometimes I save them as a draft.

I’m always afraid that something will go wrong with Wordpress and they’ll publish my drafts. So I don’t keep anything in there that I wouldn’t be willing to share with the world.

How he puts together his talks

One of the major things I spend time producing right now are talks. I give them all over the world.

Many people know me for my books, and my blog, and my workshops. But to me, those are all actually art projects. What I do for a living is I give speeches.

When I give a speech I use Keynote. I was actually one of the first users of Keynote. I live in it, and it’s the way I think about things.

When I give a talk I have about 200 slides, and none of the slides have words on them. Each has a picture and the picture brings up a story that I want to talk about. Each story is associated with an image in the presentation.

So I have large Keynote files with lots of slides in them, and depending on the presentation I’ll hide and show and rearrange slides to put together the talk that I want to give.

Some of these slides have been in there for a long time. Some of them I haven’t used in years. But I keep them grayed out in the Keynote file because I might use them again.

How a slide gets into his presentations

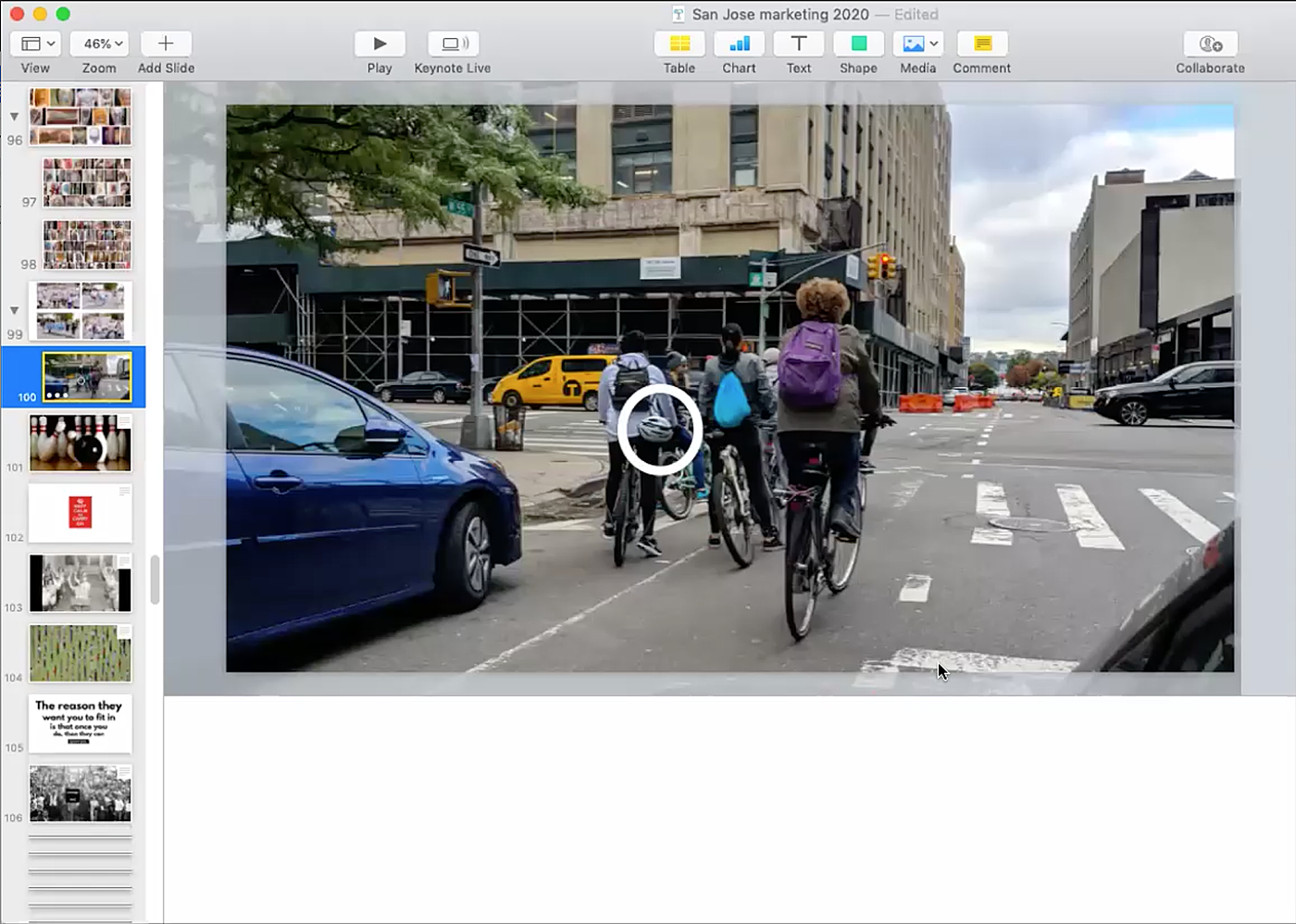

This slide is one of my favorites.

It’s a group of people biking and none of them have helmets. Except for one of them, who has a helmet attached to her backpack. She has a helmet but she’s not wearing it.

And the question is, how can this be? Why would someone have a helmet with them but not wear it?

The answer, it turns out, is that people are willing to risk their lives to fit in with their friends.

So how did this story get into my presentation? I was on 9th Avenue in Manhattan and this group of people passed me on their bikes. I noticed them out of the corner of my eye.

I noticed that this woman had the bike helmet clipped to her backpack, and that there was a story there. So I gunned it through a red light to catch up, and managed to catch them as they hit another red light one avenue over. I got out my camera and took this picture.

And that shot just lived on my phone. When I was giving a talk a few months later, I remembered I had the picture somewhere. So I dug through my phone and found it.

I don’t have any special organization system for things like this. I don’t do it for photos or files. I used to have a perfectly organized hard drive with a complicated folder structure. Now I just throw all my files into one place and just use search. It’s like the toolbox I made all the way back at Tufts.

He’s constantly testing out new riffs to find what works

I’m constantly trying out new pieces riffs for my talks by speaking to people like you.

For example, I just taught someone in my office how to juggle today. I’ve tried that riff on hundreds of people face to face. I’m not directly practicing a talk. I’m not saying, “Here, let me practice my Keynote.”

Instead, I’m taking time to teach people what I’m seeing about the world.

When I do that with someone face to face, over and over again, I can create a feedback loop that helps me understand what it does to someone’s insides when I teach them something. And that’s what helps me figure out if it should go into a talk.

I’m constantly asking myself, Why did that touch people? Then I put a bunch of these stories and riffs together and that’s my talk.

How he crafts the narrative of his talks

The narrative of my talks is always fairly organic and not very strategic. I think the same is true for every non-fiction book that has changed me: The Gift, by Lewis Hyde, or The Art of Possibility by Rosamund and Ben Zander, or the War of Art by Stephen Pressfield.

I can’t tell you the order of their chapters. I have no idea. It’s like some people think that the order of the songs on a record matter, I don’t think they do. If they had been in a different order it still would have been a good record.

I’m not thinking so much about the larger arc of the talk because I don’t believe that is actually how humans change.

The Bible is in no particular order. Religious services are in no particular order. The way we start dating someone and end up spending our lives with them is in no particular order. We just pretend that they are.

One of the things I discovered in high school is that the only reason we study biology before chemistry is because we invented biology before we invented chemistry. We should have chemistry first but we don’t.

What I do, instead of focusing on order or arc, is I try to bathe people from all different directions in a way of thinking.

When you bathe people in a way of thinking you can get them to change.

You need to teach like this because the way people change isn’t logical. We invented logic long after we became humans. People change when they decide to change, when they take off an old piece of their identity and put on another one. Like a uniform.

We see example after example. How long did it take for people to stop smoking cigarettes?

It's not just because they were addicted to nicotine, it's because they were culturally inculcated in, “This is what I am when I look in the mirror. I'm someone who smokes.”

It’s the same thing with the biker example I mentioned earlier. Everyone in your biker gang is not wearing a helmet, so you’re not going to wear a helmet. You’ll just keep it clipped to your backpack. You’re not going to wear your “Safety First” uniform if your friends aren’t.

Everyone is wearing a uniform. So I spend all my time thinking about: what uniforms are we wearing? Why is it the uniform? And most importantly:

Can we come up with a better one?

So my talks are all designed to help people understand the uniforms they wear and help them put on better ones.

How he gives presentations

Now, I also have a few specific systems that I use for giving presentations.

What will happen when I'm giving a talk, is I need to be able to communicate to people in a way that makes me fully present.

That means that I don’t use my slides as a teleprompter. Almost every single non-professional makes this mistake when they give presentations.

They flip to a new slide, then they look at the slide, and then they talk about it. I don’t do this. It’s jarring. It makes the whole thing stilted.

Instead I’ll notice that the next slide coming up is a slide about, for example, Grateful Dead tattoos. Then I’ll transition to telling that story of the Grateful Dead tattoos while I’m still on the original slide. Once I’ve introduced the story then I’ll switch to the Grateful Dead tattoo slide.

Movies do the same thing. Most people don’t know that. When you watch dialog in movies, they don’t switch from one camera to the other when the speakers switch. They switch before the speakers switch, or after. If you switch every time the speakers switch it gets jerky.

It’s the same way for speaking. Start talking about the next slide while you’re on the first one.

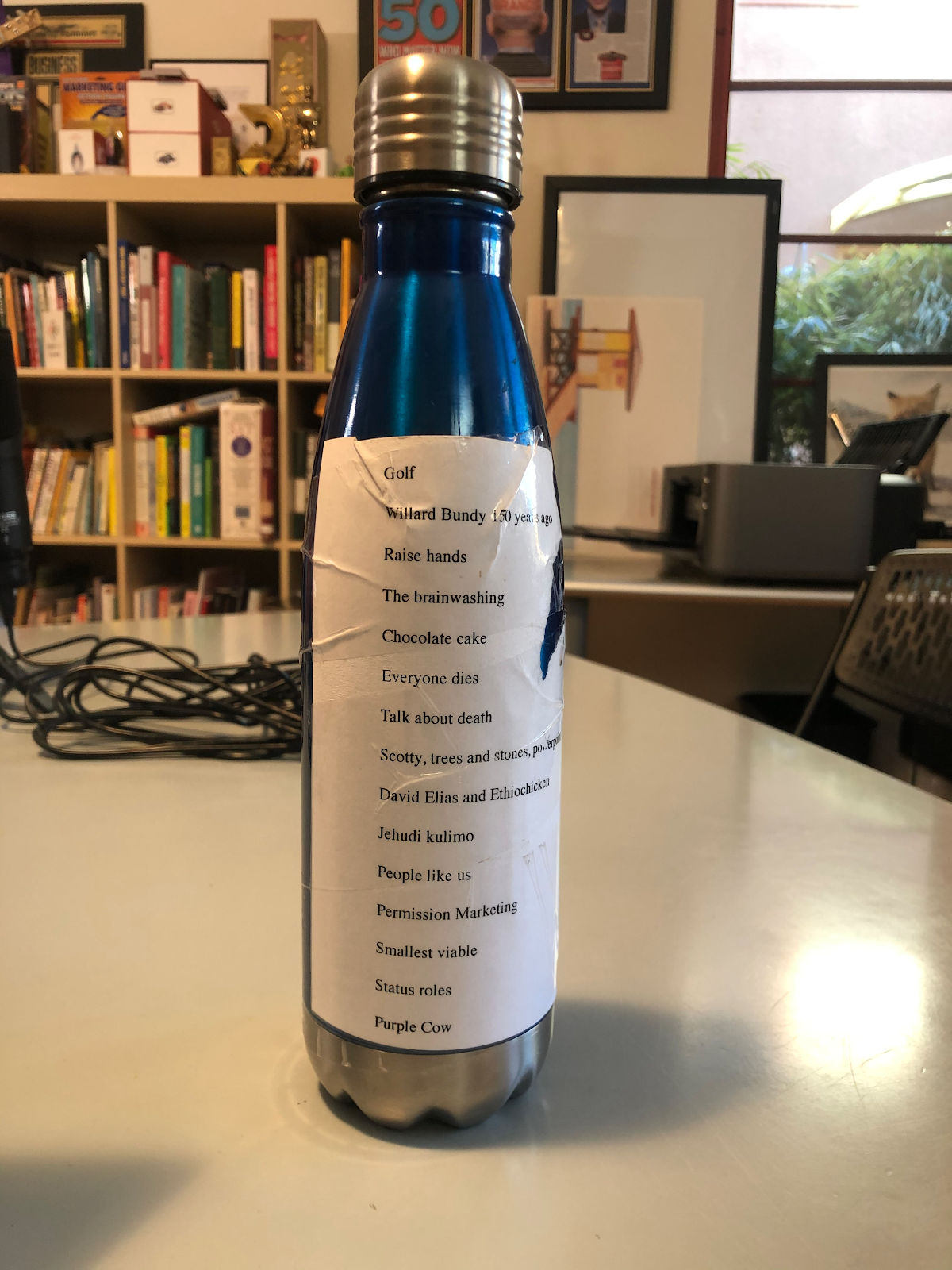

How he uses a coffee cup to give his talks in an emergency

Now, sometimes the venue doesn’t read my rider and prepare, and so I can’t use my slides.

I can’t use slides when the place only has one screen. In my rider I always ask for two screens: one for my slides, and one for a video feed of me.

I do that because if you just have your slides up, then everyone’s going to be looking at the slides. If they’re just looking at the slides and they’re never looking at me, then they’re not going to be fully engaged in the presentation, and I won’t be able to do my best work.

So I sometimes have to scrap the slides because there’s only one screen. Now, it takes a lot of preparation to give a talk with no slides. It’s much harder.

But I invented something three emergencies ago that makes it much easier.

I take a water bottle or a Starbucks cup on stage, and I stick my story list on the back. No one knows. They can’t see it.

So when I’m giving a talk and I need to know what’s coming next, I just stop in the middle of the current story, take a sip of water, and then I know exactly what the next story is going to be.

Seth’s take on happiness

I'm thrilled beyond measure and have been for a very long time. I decided to be thrilled and then I became thrilled. It didn't happen in the other direction.

There were years of doing this work where I looked for every reason to be disappointed, every reason to be upset, every reason for things to be unfair. And then one day I said, “I'm tired of living that way so let's stop that.”

Pretty consistently since then, I have found something to focus on where I feel as privileged as I truly am.

A book recommendation

The Goal, by Eliyahu Goldratt. It's the most accessible book on a topic that people truly don't understand. Even after I force people to read it, many of them still don't understand. It’s all about how growing businesses, particularly factories, suffer or thrive.

The book reminds me of my dad. My dad had a PhD in this topic. He taught at the business school in Buffalo. I used to grade his papers when I was 15. So I have an emotional connection to it as well as an intellectual connection.

Thanks for reading! Did you like this post? Make sure to tell me in the comments!

Want to make this interview more actionable? Consider getting a Premium Membership:

We’re striving to make Superorganizers Premium everything you need to live a productive life — for just $15 / month.

When you become a member you’ll get:

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I agree with Seth, dal is king.