Thinking Physically with Yancey Strickler

How the former co-founder and CEO of Kickstarter wrote and researched his new book

January 29, 2020

In 2017, Yancey Strickler quit his job as the CEO of Kickstarter, rented a small apartment in Chinatown, and started to write a book called This Could Be Our Future.

As the former co-founder of the startup that created the category of crowdfunding you might think he was writing about technology. But, no.

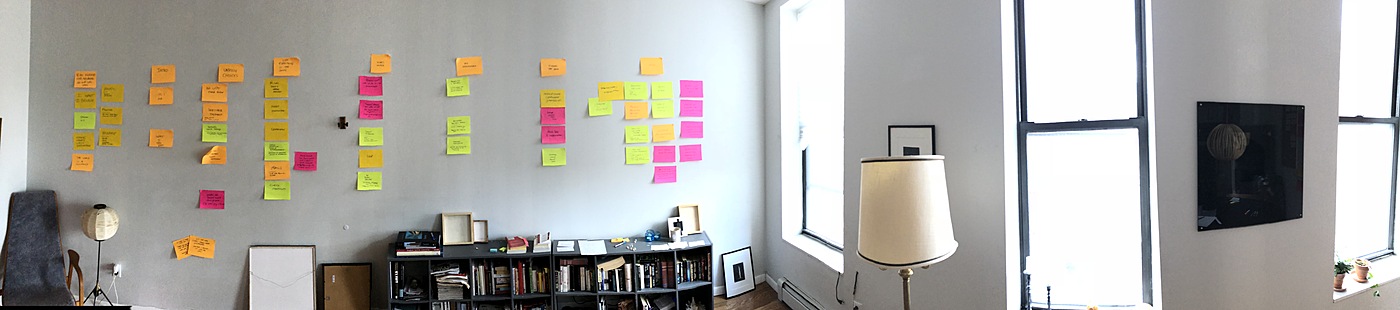

He didn’t even write with technology. He switched off the internet completely, and turned the walls of his part-time garret into a canvas painted from wall to window with splashes of Post-Its, and decorated with stacks of books on post-capitalist theory.

“It started out being really scary,” he says. “The second day was so hard because I had to touch deeper parts of myself than I’d had to touch in a long time. And I was the only person there in this apartment.”

Yancey was writing about where capitalism has failed, where it has succeeded, and how it should change in order to create a better future for all of us.

But even though he was on the hook to write and publish the book in just a year, he hadn’t yet even figured out what the central metaphor for it was going to be. He had to figure that out as he went along.

So, how did he come up with bentoism — his idea for how to change capitalism? How did he synthesize the best thinkers in the history of economics in order to write his book? And how did he actually write the book itself?

We cover all that and more in this interview. Let’s get to it!

How the book began

From the start, I knew this project needed to kick my ass.

I knew that from the second the starting gun sounds, I needed to push myself. So I created as many structures as I could to help me produce my best work.

I knew I was going to write a book about expanding our conception of what it means for something to be valuable. But I needed to figure out: how do I tell that story?

He used the physical space to develop his ideas

In the beginning, my process was very physical. I barely used my computer. The computer is a very rational experience. The most liberating space to be creative is actually the world around you: the walls, the floor, or the moleskin on your lap.

I gave myself a year to write the book. But for the first month, I only read.

I read Adam Smith, Karl Marx, Thomas Piketty, and other economists, historians, and philosophers who thought about value. I would sit on the floor amid all these books, pulling out ideas and writing them on Post-It notes.

I covered the space with hundreds of Post-Its of ideas that stood out to me.

I have such strong memories of walking around the apartment looking at these notes, and trying to imagine them in my mind.

It turns out that if you put a bunch of these Post-It notes on a wall from the books you’re reading, the larger topics start to organically emerge from them. It’s this bottom up process.

So I would read a bunch of interesting things, and then lay them out in front of me and ask myself: What is this about? What’s actually important about these things? Sometimes it was nothing, and sometimes you realize: Oh, this is about worker pay.

The process of seeing them manifested physically in front of me was so helpful. You're just flowing, thinking about all of these ideas and how they fit together.

And soon, I was kind of able to see these Post-Its transitioning into a book, as if they were in a stop-motion animation.

Then I started refiltering the Post-Its back into an outline I had written — that helped me winnow down what was supposed to be in there and what wasn’t.

He wrote the book itself using Scrivener

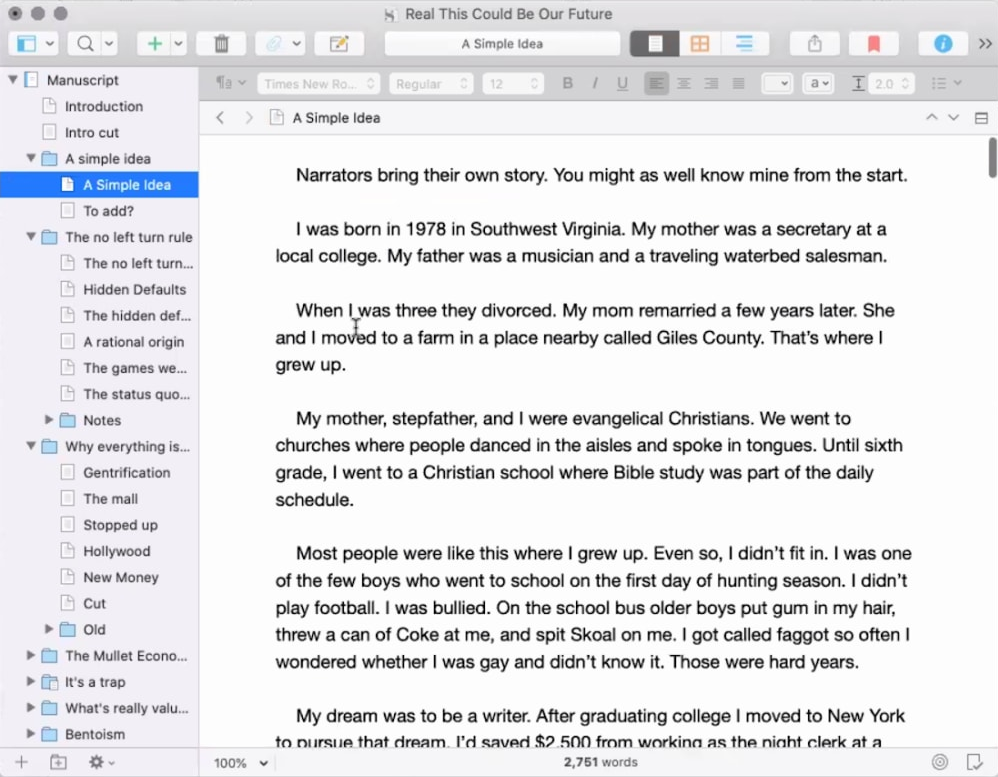

I used the word processing program Scrivener to help me turn my outline into chapters.

I like Scrivener because each chapter becomes its own folder made of sub-documents. This allows you to compile your ideas and connect them, but also keep them somewhat distinct so that you can rearrange them easily if you need to.

That’s what you’re seeing below. Each chapter becomes an index card on a corkboard. That way you can get a sense for what each chapter is, and easily rearrange them as your narrative changes.

This was especially helpful because I like to break up my ideas to make them more digestible. I envisioned the book like an Adam Curtis documentary, with an emphasis on montage. I wrote it chunk by chunk, with 300 here and 1000 words there. The structure of Scrivener let me reflect the style of the book I was trying to create.

The process felt like watching this miracle of watching the folders accumulating one by one.

How he structured his writing time

I took about a month to write each of the first few chapters. Eventually, though, I could do a chapter in about three weeks.

I wrote each chapter in a very visual way. I spent a lot of time trying to picture what the words would look like on the page and how the reader would experience the text.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!