.50.43_AM.png)

The history of the personal computer wasn't just about technology—it was about vision, trust, and the courage to stand up to a monopoly. In his latest piece for The Crazy Ones, Gareth Edwards tells the story of how Compaq challenged IBM's dominance in the 1980s. When IBM tried to reclaim control of the PC market with proprietary technology, Compaq CEO Rod Canion decided to create an open standard and share it with competitors—effectively giving away "the company jewels" to preserve innovation. Gareth explains how Canion's leadership style created both a beloved workplace culture and the backbone needed to face down the industry giant. Just think—if IBM had won, we might be living in a very different technological landscape.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

As CEO of Compaq, the most successful of the companies making IBM personal computing “clones,” there weren’t many people Rod Canion would always take a call from. Bill Lowe, the head of IBM’s personal computer business, was one of them.

It was September 9, 1988. The two men chatted amiably for a few minutes before Lowe made Canion an offer. IBM was prepared to give Compaq unparalleled access to its new, proprietary next-generation PC technology. All Canion had to do in return was cancel the press conference Lowe knew he had planned for the following week.

The call caught Canion off guard. The conference was to announce that Compaq and eight other major PC companies had agreed to keep the current PC technology as an open design standard, in outright opposition to IBM. Yet here was Lowe with a counter-offer: Abandon the others. Split control of the multi-billion-dollar PC market between Compaq and IBM. The two companies could rule it together.

The financial upside for Compaq was huge. It would be insane to turn it down. Besides, everybody knew you couldn’t win against IBM. There was silence for a moment. Then, calmly and politely, Canion gave Lowe Compaq’s answer.

Lowe listened and sighed. “I think you’re making a big mistake,” he said, and ended the call.

Four days later, Canion stepped onto a New York stage and did the unthinkable. He declared open war on IBM.

This is the story of Rod Canion and Compaq. It is the story of the battle for the soul of the personal computer, and the fight to prevent IBM from taking back full control of the technology behind it. It is based on contemporary accounts in the New York Times, Time, PC Magazine, Byte, and Infoworld as well as books such as Blue Magic by James Chposky and Ted Leonsis, The Fate of IBM by Robert Heller, Big Blues by Paul Carroll, and Open by Rod Canion. It draws on interviews with key figures such as Ben Rosen and L.J. Sevin conducted for the film Silicon Cowboys and for the Computer History Museum. It is also based on interviews with Rod Canion conducted by the author himself.

Bring order to content chaos with your AI encyclopedia

Recall isn’t just another AI notetaking tool—it’s a way to turn everything you encounter online into a living, evolving knowledge base. Recall transforms scattered content into a self-organizing, interactive encyclopedia—connecting what you read, watch, and save into one dynamic system.

- Save time with high-quality, one-click summaries

- Get straight to the point by chatting with your content

- Automatically organize data into a dynamic knowledge graph

- Reinforce memory with personalized, spaced repetition quizzes

- Turn stored knowledge into active intelligence with just-launched Augmented Browsing, which surfaces related content from your knowledge base as you browse

FYI: If you're a Pocket user looking for an alternative, check out Recall—it just launched Pocket imports and offers a solid AI-powered read-it-later experience.

Experience Recall today and elevate the way you consume content forever. Use the code Every20 for 20% off a subscription to Recall. Valid until July 1, 2025.

Starting the company

Rod Canion, Jim Harris, and Bill Murto were company men. By 1981, all three had worked at Texas Instruments (TI), which made electronic products like calculators and computers, for years. In their forties with families, they were more likely to be seen in crisp suits and ties than the loose shirts and slacks already the stereotype in Silicon Valley.

Yet in September 1981 the three friends sat around the dining table in Murto’s Houston home and questioned their future at TI.

“We got a bad boss,” Canion said later. “He just wasn't fun to work for. He wasn't a bad person! Just… not a good boss."

It didn’t help that all three of them made regular trips to TI’s contractors or clients in Silicon Valley. They’d see the Porsches and Ferraris in parking lots. Maybe that could be them. They decided to form a company of their own.

They briefly considered setting up a restaurant—Mexican food was a shared passion—but swiftly discarded the idea. They were all passionate about, and had worked with, computers. So they decided to do something for the IBM PC.

"It was obvious to anybody paying attention, there was gonna be an explosion in the PC market." Canion said.

The PC was designed to be expanded. Not just by IBM, but by anyone. Any company could create plugin computer boards, peripherals like disc drives, or accessories that would work with the machine. This “open architecture” approach was a bold thing for a company to do. That Big Blue (IBM) had chosen this path seemed miraculous. It liked making big, expensive computers that nobody other than IBM was allowed to touch. But Don Estridge, the creator of the PC, believed that the best way for IBM to succeed in the home and small business market was to make a machine that used common industry parts and acted as a standard platform. It worked. By September 1981, the PC was the hottest item in computing, on track to sell more than 250,000 units by the end of the year.

At TI, Canion had led a hard drive project for a different type of computer at TI. It was how he had met Harris and Murto, so doing the same thing for PCs felt like it would be familiar ground. Leaving TI would be tough, though. All three men had little savings. They needed venture capital, but in 1981 that industry barely existed and what investment was available was mostly focused on Silicon Valley. Canion and the others didn’t know how to access venture capital, or who could provide it.

Luckily, Canion soon encountered someone who could help: Portia Isaacson.

Isaacson was ex-U.S. Army. After she was discharged in 1962 she worked as a programmer at Bell Helicopter, Lockheed, and Xerox PARC. Then, in 1974, a company called Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS) released the very first home (or “micro”) computer—the Altair 8800. Isaacson fell in love with it. By 1981, she had founded a consulting firm in Dallas focused on predicting trends in computing.

Canion met Isaacson in October 1981 when she came to Houston to consult for TI. Sensing that she might be able to help, he gave her a lift back to the airport after her work in Houston was complete.

Humble and soft-spoken, with a gentle Texas lilt, Canion’s relaxed attitude concealed a quick mind that contrasted with the brash and flamboyant personalities that dominated senior management at most technology firms at the time. He didn’t over-promise on projects; he delivered. He didn’t boast about his successes; he shared credit. Isaacson liked him. Not only did she give him the advice he needed, she went one further. She connected him with her friend, L.J. Sevin.

Sevin had cofounded chipmaker Mostek. In 1979 the firm sold for $345 million—about $1.5 billion today. Less than a month before Canion’s conversation with Isaacson, Sevin teamed up with New York technology analyst Ben Rosen to launch a venture capital firm called Sevin Rosen. Sevin had worked at TI before founding Mostek, so Isaacson suspected the two men would get on. There was also something else that made Sevin, as a newly minted venture capitalist, very rare. He lived in Texas.

“I think he liked us because he didn’t have to fly anywhere,” Canion joked later.

Sevin liked Canion’s hard drive idea, and so did Rosen. They agreed to pitch it to other venture capital firms to see if they could secure a second backer, something they required before they’d invest. Sevin also gave Canion a warning.

“Don't take anything with you but what's in your mind,” he said.

"We knew that they would sue us if we stole anything,” Canion said later. "L.J. [Sevin] reinforced that though. There's no doubt."

From the beginning, Compaq’s founders understood the danger of being accused of intellectual property (IP) theft.

On December 4, 1981, Canion and Harris resigned from TI. Murto followed a few months later; his wife had just had a baby, and the couple needed the post-natal care his insurance was providing.

The portable

Canion and Harris were together at Harris’s house a few days afterward when the phone rang. It was Ben Rosen. Rosen told them that he’d been unable to find a second investor for their hard drive plan. But if they could find a new idea, then Sevin Rosen would be happy to look at that, too.

Canion and Harris could have withdrawn their resignations from TI. Instead, they decided to double down. They registered their new firm (with the holding name of “Gateway Technology”) and paid $1,000 each into its bank account.

“Our excitement about starting a company was tempered by the knowledge that we had set aside only six months of living expenses for our families,” Canion wrote later.

They had six months to come up with an idea that Sevin Rosen would back.

A lot could change in six months. Indeed, just six months earlier, the writer and flamboyant technologist Adam Osborne had stunned the world of computing by launching the first truly portable computer, the Osborne 1. Canion found himself musing on that at breakfast one January morning in 1982. Then it came to him.

“I was struck by an idea that was so simple and obvious it sent a chill down my spine,” Canion wrote. “What if we could make a portable computer run the software written for the IBM PC?”

It seemed like such an obvious idea that they couldn’t believe that someone else wasn’t trying it already. As they worked through the details, however, they realized there was a difference between obvious and easy.

Computers are more than just software and hardware. Software rarely interacts directly with the hardware on which it runs. It runs within an operating system (OS), such as Windows or Linux today. That OS talks to the hardware using a shared language of instructions and routines, known as the Basic Input/Output System (BIOS), burned into a chip on the hardware itself.

One reason Don Estridge was confident about his open approach to the PC’s design was that although anyone could put together similar hardware, the BIOS IBM’s PC used was proprietary code—the intellectual property of IBM. A company wanting to “clone” (as it became known) the PC would need to write its own BIOS, but to run the same OS and software as the IBM PC, it would need to respond to every instruction exactly the way IBM’s own BIOS did. Otherwise, the OS and software would crash.

Creating the hardware for a portable clone of the IBM PC was easy. Replicating the BIOS in a way that wouldn’t infringe on IBM’s copyright was hard. The men believed they knew how to do it, though.

Creating a clone

“You crazy bastards,” Sevin said.

It had taken a few weeks to pull together a technical specification for a portable PC. After that, Harris and Canion sat down in a Houston House of Pies with a retired industrial designer named Ted Papajohn. On the back of a placemat, Papajohn created a rough sketch of a prototype according to their instructions: It needed to look like an Osborne 1, but “less army surplus.”

That specification, a business plan, and a cleaned-up photocopy of Papajohn’s visualization was in the presentation they had just handed to L.J. Sevin and Ben Rosen.

Both Sevin and Rosen were doubtful. Creating a portable PC clone seemed an insurmountable challenge.

“We liked the guys,” Sevin admitted later. “I did a little background checking on Rod [Canion] and it all came back positive.”

A few days later, Rosen called Canion and Harris. He confirmed that Sevin Rosen would provide investment capital, conditional (once again) on another investment firm joining them. This time, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers agreed to do so. With a total $3 million investment, Compaq—as the company would soon be renamed—was a go. Rod Canion became CEO while Ben Rosen agreed to serve as board chair.

Design work on the “Compaq Portable” began in March 1982. The Compaq founders had persuaded a number of TI employees to jump ship with them, though they’d had to be intentionally vague on what the work would involve to avoid legal issues with TI. This group included hardware engineers Steve Ullrich and Ken Roberts, who would prove critical to working out how to clone the IBM PC, and Steve Flannigan, a software engineer. As soon as Ullrich and Roberts joined, Canion was contacted by a third TI engineer, Gary Stimac. He was so desperate to join the others at Compaq that he’d already handed in his notice at TI. So they hired him as well.

At their new Houston offices and (according to Stimac) after plying their new engineers with enough pizza to soften the shock, Canion, Harris, and Murto told their new employees what they needed to do: Create a portable IBM PC clone. And not just one that could run some IBM PC software—other companies were already boasting about that—but a clone that could run all of it. One hundred percent compatibility. When they questioned this, Canion insisted that anything else wouldn’t stand out from the crowd. One hundred percent compatibility. No less.

It was a huge challenge, not least because, with PCs selling so well, it was hard to find a retailer that had them in stock. Stimac found one in Dallas, and flew there to buy a machine. He returned triumphant. Not only had he bought a PC they could dissect, but he’d also read its technical manual on the plane. That manual contained a full breakdown of how the PC’s BIOS worked. He told Canion and Flannigan he was confident that he could copy it. Canion and Flannigan groaned.

“Stimac had unknowingly contaminated himself by looking at the code printed in the IBM manual,” Canion wrote.

IBM printed the technical breakdown of its BIOS because it made it easier for software or peripheral makers to create products for the PC. But that didn’t stop the BIOS from being proprietary technology in the eyes of the law. If Stimac now worked directly on a BIOS that replicated its functionality, IBM’s lawyers could claim copyright infringement.

Many clone manufacturers would fall prey to this honey trap over the years. Big Blue would dispatch hordes of lawyers to descend on them. The inevitable result was bankruptcy or huge licence fees that reduced their ability to compete.

So Stimac, Flannigan, and Compaq’s legal counsel sat down together and worked out a way to create a functional specification for a cloned BIOS—one that would allow them to leverage Stimac’s knowledge without contaminating anyone else and leaving them open to legal action from IBM.

Stimac would read the documentation, and from that he would describe how the BIOS functioned to a lawyer. The lawyer would then write a functional specification based on what he said, stripping out any information they felt was proprietary to IBM at this stage. The resulting specification was given to Flannigan and the other engineers. They would use it to create a “best guess” clone of the BIOS and fix any mismatches in behavior through trial and error.

This became known as the “clean room” method. It was resource-intensive and time-consuming. But it worked.

“Nobody in the entire office could ever buy a copy of a technical manual after that without me removing the [BIOS] pages and destroying them,” Stimac said later.

Unable to work directly on the BIOS, Stimac was instead tasked to source an operating system that was fully compatible with IBM PC software.

This should have been relatively easy. The computer used an operating system called PC DOS (Disk Operating System), made by Microsoft. In negotiations with Microsoft founder Bill Gates, IBM had agreed that in return for a cheap per-unit license, Microsoft could sell a version as “Microsoft DOS” to other companies as well.

It was a deal that IBM regretted almost instantly once its PC became popular because companies like Hewlett-Packard—and now Compaq—could buy a version of DOS to run on their “PC clones.” And it was this ability to sell the non-IBM PC version of its software without IBM getting a cut that made Microsoft the financial success it is now. In theory, software made for the PC should now work on these clones. But as Stimac started testing Microsoft DOS with Compaq’s new computer, he spotted something odd. Microsoft DOS was meant to be exactly the same as the PC DOS, but it wasn’t. It would occasionally cause PC software to crash or not run at all on a clone.

Other clone companies likely attributed these crashes to flaws in their hardware or cloned BIOS. Stimac was convinced it was a problem with Microsoft DOS itself. So, in March 1982, Rod Canion traveled to San Francisco to meet with Bill Gates. The two men chatted amicably for a while. Canion looked Gates squarely in the eye and revealed what Stimac had told him:

“The Microsoft DOS you are currently selling us and everyone else isn’t compatible with PC DOS.”

After a pause, Gates smiled and admitted that Canion was correct. While they had started out as the same software, since the PC’s release, Microsoft DOS and PC DOS were developed by two separate teams within Microsoft. Those teams weren’t allowed to cooperate. That was a secret part of his agreement with IBM. So while the products were mostly compatible, they were actually slightly different.

Impressed that Compaq had worked this out, Gates agreed to talk to his lawyers and see if there was a loophole that would allow him to sell PC DOS, rather than Microsoft DOS, to Compaq instead. A few weeks later he contacted Canion and told him that, regretfully, there wasn’t. He had been advised that he could, however, tell Canion which exact version of DOS was the last one created by Microsoft before development between the two teams had diverged.

Canion took the hint. He licensed that last version of DOS before development diverged. Stimac’s team was expanded, and he was told to turn this version of DOS into their own product, “Compaq DOS,” one truly compatible with PC DOS. Compaq, it seemed, was in the business of cloning an operating system as well as a BIOS.

In June 1982 Compaq revealed a prototype of the Compaq Portable at the National Computer Conference in Houston. It swiftly became clear that Canion’s instinct that there was demand for a portable PC clone was correct. Everyone was wowed by their prototype. What nobody knew was that Compaq was cheating. Although the hardware was real, the BIOS and OS it was running were the genuine IBM versions. Compaq’s were not production-ready.

They spent the next nine months racing to finish their BIOS and bring Compaq DOS up to full feature parity. They also set up a manufacturing plant in Houston. Now they needed to set up a dealer network.

"If we could get the best person in the world to come do this job, who would it be?” Canion remembers thinking. “Well, it was kind of obvious… who set up the IBM distribution channel?"

That man was H.L. “Sparky” Sparks, one of the first people Don Estridge had brought onto his PC project at IBM. Through John Doerr, the chairman of Kleiner Perkins, Canion reached out.

"He lined up a secret meeting between Sparky and me in the Dallas airport." Canion remembered later.

Shortly afterward, Sparky joined Compaq. By the time of its launch, the Compaq Portable could be found in many dealerships sitting alongside the IBM PC.

Compatibility is king

The Compaq Portable launched in March 1983. In their initial proposal to Sevin Rosen and Kleiner Perkins, Canion, Harris, and Murto had claimed Compaq could potentially hit first-year revenue of $30 million (roughly $96 million today). Everyone believed it was an optimistic target.

In its first year, Compaq made $111 million ($350 million today), a record for a new business in the U.S.

The Compaq Portable was nothing like what we’d call a laptop today. It weighed 28 pounds (the average weight of a two-year-old) and folded up into a case roughly the size of a sewing machine. But you could put it in your car and take it home, or bring it on a plane. Most importantly, the Compaq Portable used a version of DOS. In the days before copy protection, you could use your IBM PC software on it instead of having to buy all your software twice. This wasn’t true with the Osborne, which used a different operating system.

"If it was running on an IBM PC already we'd make it work on ours. We'd even create flaws that would be comparable to IBM's flaws,” Canion recalled. “That was one of the funny issues when it first came up: Do we do it right, or do we do it the way IBM did it? We were extreme about that... but the answer was always: We're gonna always do it the way IBM does it."

Other clone companies fell into the trap of trying to improve on the PC, or made compatibility compromises to lower the cost. Compaq’s ruthless commitment to compatibility set it apart.

That compatibility promise would have been worth nothing if Compaq’s Houston factory had failed to deliver in output or quality. But Canion grasped that a happy, well-paid, and well-informed workforce would perform better. Harris and Murto agreed. Feeling underpaid and undersupported by management was why they’d all left TI. Compaq built a reputation in Houston for being a good place to work. It wasn’t just the pay, it was the way you were treated. The Coke machines were free. If they ran out, Harris or Canion would pop out to the grocery store. Sometimes they’d have to walk quite a way across the parking lot when they got back—there were no guaranteed C-suite parking spots at Compaq.

“How often do you get to work early to get your job done, and you can't find an unreserved parking place?” Canion said. “It just seemed to make sense that the people who got there first would get closest to the door.”

Canion also believed that shared knowledge and accountability was critical.

“People make mistakes when they don't know what's going on. When they don't know all the facts. The more they can be aware of the whole picture, the less likely they are to make a mistake. It's that simple. So the more I could tell them about what we were trying to do, our plan, then when they saw something that didn't fit with that they could raise their hand. And maybe they were right and maybe they were wrong. But at least we had a culture where they were free to raise their hand and didn't get punished if they were wrong.”

As a culture it proved effective, and it also scaled. But Compaq’s success brought it ever closer to the inevitable: a battle with IBM.

The IBM Portable

IBM didn’t see Compaq as a threat. The PC was selling faster than IBM could get it onto the shelves. And a shrewd move early on had kept Compaq out of the crosshairs of IBM’s lawyers.

“Steve Flannigan had run into a bunch of IBM software guys from their PC group at conferences,” Canion remembered. “He bragged about how careful we had been not to copy anything.”

IBM also had no interest in making a portable computer at first. By the end of 1983, though, rumors began to circulate that this had changed. At Compaq, orders from dealers started to drop. Everyone was waiting to see what IBM would do.

By January 1984, orders ground to a halt. Compaq faced a crisis. The obvious thing to do was start cutting production and staff, at least until IBM announced the specifications of its machine. But if it did that it would be impossible to ramp production up again fast enough to compete. It would also damage its reputation. The alternative was to keep running the production lines and try and weather the drought.

"It was one of the few times where I've had to say 'There's no successful path out of this, unless something is wrong with their product... so we're gonna keep building,’" Canion said later.

With inventory not leaving Compaq’s factory and no other place to store it, they began hiding it in unmarked semi-trailers in parking lots around Houston.

In February 1984, IBM finally revealed the specifications of the IBM Portable. It was heavier and less powerful than the Compaq Portable. Almost overnight, Compaq’s sales rebounded beyond even the level it had been at before. IBM’s big announcement had whet the market appetite for portables. The tractor trailers sitting in Houston parking lots were sent out onto the road.

Inventing backward compatibility

When IBM revealed the specifications of its portable, remarkably, it wasn’t fully compatible with all existing IBM PC software. This was because it was based on the XT chipset—an iteration of its PC design that IBM had launched in mid-1983.

That IBM had broken software compatibility without warning on the XT caused some consternation. Businesses upgraded their computers, only to discover they would have to spend thousands of dollars buying updated versions of software they already owned. Within Compaq, where compatibility was now hard-wired into its corporate DNA, IBM’s cavalier approach to compatibility seemed astonishing. Canion insisted that every new Compaq machine had to work with what had come before, even if IBM’s didn’t. The concept of “backward compatibility” was born. Businesses started to realize that if you wanted your old IBM software to work on a new machine, you were better off buying a Compaq.

By creating a portable, IBM had broken the unofficial truce between the companies. Now it was time for Compaq to play in IBM’s yard, too. When Stimac asked to create a new desktop PC clone, Canion signed off. The Compaq DeskPro was launched in June 1984 to critical acclaim. Two months later, in August, IBM launched an even more powerful machine, the IBM PC/AT. But companies buying the PC/AT experienced the same problem others had found with the XT—their software wasn’t guaranteed to run on it. IBM had ignored backward compatibility yet again. Compaq was able to make significant gains because the DeskPro, though slightly less powerful, still offered full compatibility with older IBM PCs.

Although the DeskPro was a success, the PC/AT, which used Intel’s brand-new 80286 (“286”) chip, was a reminder of IBM’s near-symbiotic relationship with the chip-maker. IBM always got access to Intel’s new chip designs first. Compaq had tripled its revenue to $330 million (about $1 billion today), but it seemed to Canion that the company would always be second on the chip curve—that was, unless IBM did something silly.

Then, in 1986, IBM did something very silly indeed.

The 386

In 1985, Compaq released a Portable 286 and a DesktopPro 286. Both machines were, once again, fully backward compatible. This was no mean feat. The changes in chip architecture at this time, between each generation, were huge in comparison to today—partly why IBM didn’t bother. That Compaq was finding ways to do it, however, was drawing attention.

In January 1986 Hugh Barnes, one of Compaq’s lead engineers, came to Canion with an extraordinary piece of gossip. Barnes worked closely with the engineering team at Intel. They said that Intel’s next chip, the 80386 (“386”), was ready, but IBM had said it didn’t want it yet.

Canion picked up the phone and called Andy Grove, Intel’s president. The two men had built up a good relationship over the last few years. Grove was surprised that Canion had heard that IBM didn’t want the new chip yet, but he confirmed it was true. This was a huge problem for Intel because designing the chip was only half the battle. The company needed IBM to do all the development necessary to make it work as part of a complete PC. Until IBM was prepared to do this, it couldn’t bring its new chip to market.

Canion commiserated with Grove and humbly made a suggestion. Perhaps Compaq could be the development partner Intel needed for the 386 instead.

Grove was surprised. This represented an extraordinary financial commitment on Compaq’s part. During their early development, new chips were notoriously buggy. They were called risk wafers because whole production runs—costing millions to produce—would be unusable. The only way to get to a working chip, however, was to keep doing these production runs, testing the chips and improving them.

Covering the cost of these failures, as well as paying for the large engineering team necessary to help find and fix the chips, represented a commitment of millions of dollars from Intel’s chosen partner. This was why Intel needed IBM. Until now, it had been the only company that had deep enough pockets and skilled enough engineers to act as Intel’s development partner.

This was Compaq’s first genuine opportunity to move ahead of IBM, however, and Canion wasn’t going to miss it. Canion offered to provide both the money and engineering teams Intel needed to bring the 386 to market. Realizing for the first time that Intel had an option other than IBM, Grove accepted.

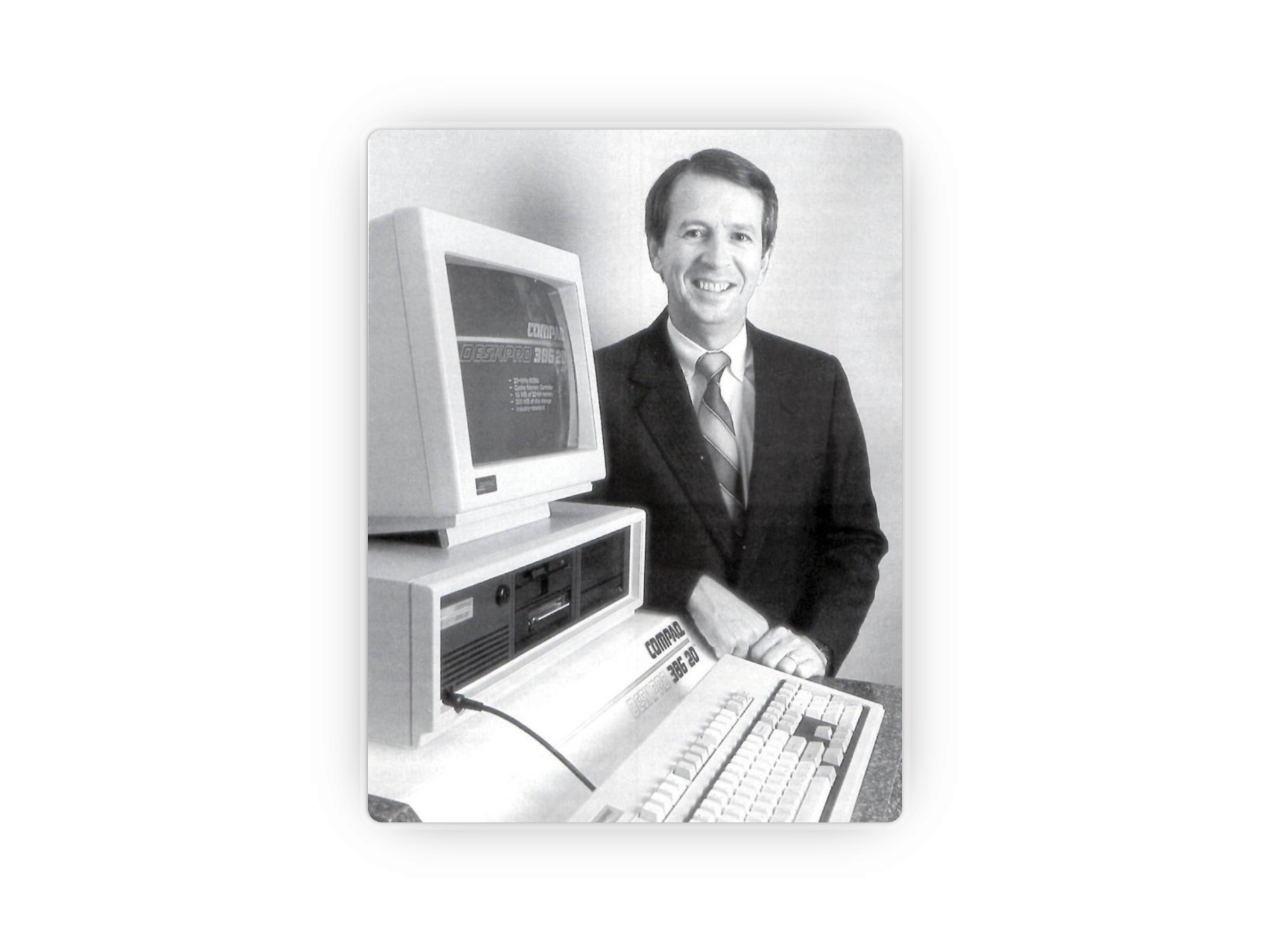

On September 9, 1986, alongside Intel founder and chairman Gordon Moore, Rod Canion announced to an astonished press the release of the Deskpro 386. Compaq and Intel had worked in tandem to bring the new chip to market, and here was the result. The first of a new generation for the PC standard—made by Compaq, not IBM.

Taking back control

In December 1982, ahead of the launch of the Portable, Canion visited Boston. There he had demonstrated Compaq’s new machine to the Boston Computer Society and answered the question everyone was thinking, even then. Would IBM ever stop making PCs to an open standard, and go back to making machines using proprietary technology?

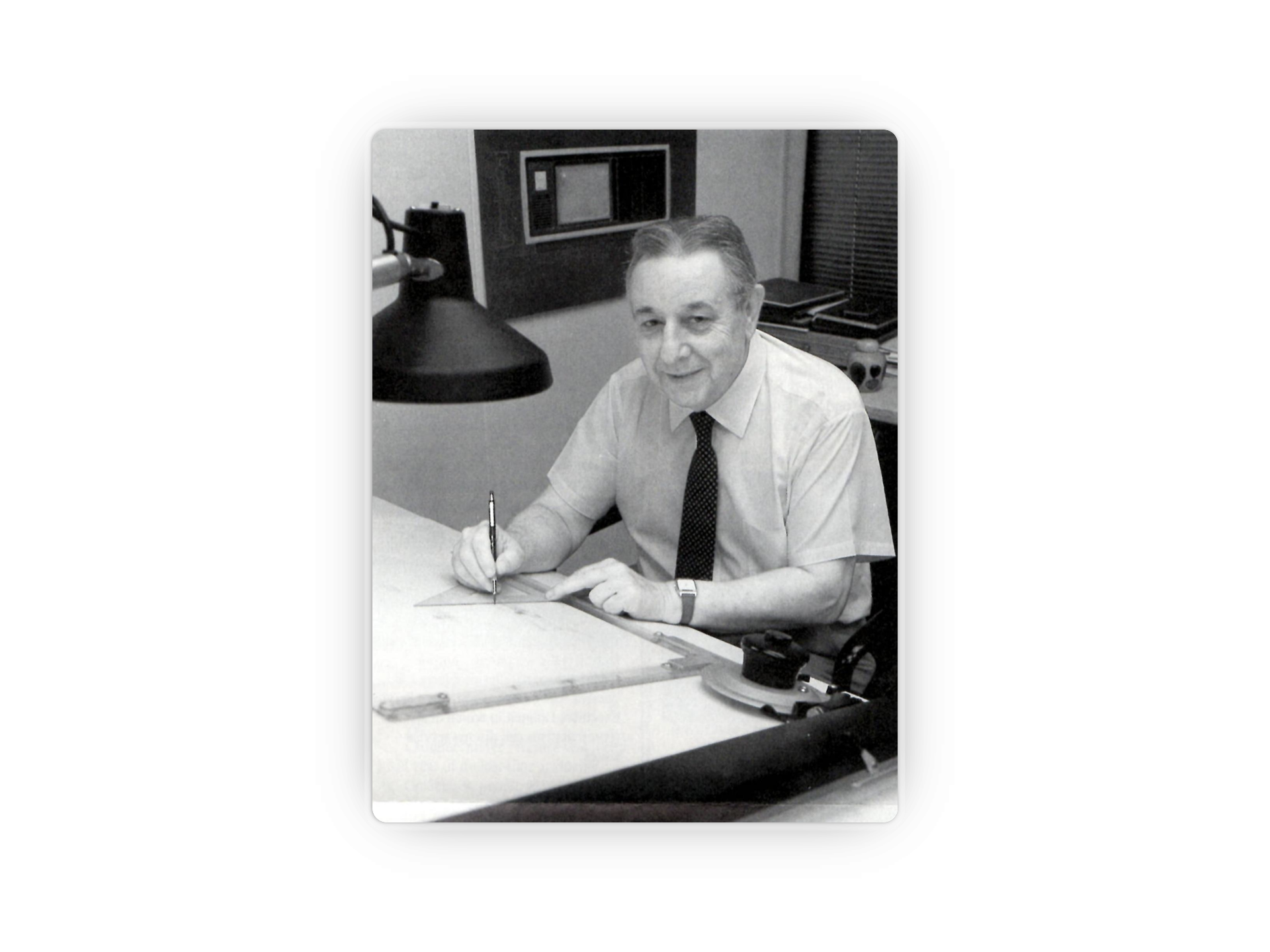

Canion spoke at the December 1982 meeting of the Boston Computer Society. Source: YouTube.

“Fears of IBM destroying compatibility by changing a bit somewhere in the PC are totally unfounded… it would greatly hurt IBM’s business,” he said.

In 1982, Canion had made the correct assessment of IBM. But that was Don Estridge’s IBM. Estridge’s vision was simple: Be the best, and share the rest.

“I only met him once,” Canion remembered. “Great guy.”

By 1986, though, Don Estridge was dead.

Bill Lowe, one of IBM’s senior executives, took over the PC division from Estridge. Lowe was a talented manager and engineer, but he was not the ideological rebel within IBM that Don Estridge had been. He was a member of IBM’s “mainframe mafia”—a culture rooted in IBM’s traditional focus on big computers and big businesses.

Although Canion and Grove couldn’t know it, this association was why IBM had refused to work with Intel on the 386. Don Estridge had intended to. Bill Lowe had no desire to. IBM’s large computer divisions, specialists in room-sized machines for serious computational tasks, said the 386 was powerful enough that companies might stop buying its larger machines. Lowe agreed. IBM’s chip division hated that the PC used Intel chips instead of its own proprietary ones. Lowe agreed. IBM’s software division thought it was ridiculous the PC used Microsoft DOS instead of something it had built internally. Lowe agreed.

IBM’s internal politics screamed that the PC needed to be proprietary technology again. So Lowe set out to make that happen. He would cut off Intel, force Microsoft out of the picture, and develop a new, proprietary PC standard that would destroy the clones, or at least force them to pay substantial fees to IBM.

In April 1987, IBM announced the latest computer in its PC range, the IBM PS/2. It was built around a new 32-bit technology called the “Micro Channel expansion bus.” The Micro Channel was entirely proprietary, and incompatible with the existing PC standard. From this point on, the clone companies would need to buy a licence to use the Micro Channel technology from IBM.

“My first reaction, when I saw the announcement of the PS/2?” Mike Swavely, then Compaq’s vice president of sales, remembered. “It was 'Oh… shit.’"

The PS/2 was a nuclear bomb dropped on the PC industry. If the clones couldn’t find a way to retro-engineer the Micro Channel and create their own version, there was no way for them to make machines without licensing it from IBM. It seemed like IBM had won. One by one, they began to negotiate with IBM.

Compaq, however, came out fighting.

“It was so important that we risk the company to keep them from winning, because we saw it—every other company, Dell, HP, everybody had licensed the PS/2,” Canion said later. “They were rushing to be the first with a PS/2. They were gonna be the Compaq of the PS/2 world. Well, that was a dead-end street. What's your reward for that? You get to live longer than everybody else and still die?"

The industry had a standard, Canion insisted in the press, whether Bill Lowe and IBM liked it or not. IBM may have started it, but it wasn’t theirs anymore. They couldn’t just discard it and ignore it.

Within Compaq, engineers were doing what they did best: trying to retro-engineer IBM’s new technology. Concurrently, though, they began work on their own equivalent to the Micro Channel expansion bus—one compatible with past PC technology, but not compatible with what IBM was offering.

Work continued on both options for a while, but by Christmas 1987 it became clear to Canion that the only way they could beat IBM was to do something commercially unthinkable.

“It hit me at some point. We're the only one that can do this. If we don't, it won't happen. We have to build the standard and maintain it. And to some degree we have to give the company jewels to our competitors. And in the end... we gave them everything. I'm sure IBM never imagined anyone would ever do that. It was 180 degrees from their business philosophy.”

In an all-hands meeting at Houston in January 1988, Canion stood in front of Compaq’s engineers and made an announcement. There would be no more doffing the cap to IBM. Compaq was going to defend the existing standard. They would finish their Micro Channel rival, and then they were going to give it to every other clone maker out there for free. The room erupted into a deafening roar as 300 engineers cheered.

Forming the resistance

Having made the decision to cross this technical Rubicon, Canion’s first call was to Bill Gates at Microsoft. Compaq and Microsoft had built a far closer working relationship than anyone at IBM likely knew.

That relationship had been established in late 1982. Back then, Gates had contacted Canion and asked, with some concern, if Compaq was trying to get into the operating system business. Surprised, Canion denied it. Gates told him that Microsoft was hearing worrying reports from the dealer network. People were buying copies of Compaq DOS, rather than Microsoft DOS, without buying a Compaq PC.

Both men knew why: Microsoft DOS had never been a true copy of PC DOS, as Gates had admitted to Canion during the development of Compaq’s first machine. The differences had only increased over time, as Microsoft’s deal with IBM prohibited the same developers working on both versions. Compaq had made its own version of DOS since the beginning. With its singular focus on 100 percent compatibility, the result was a product that was more compatible with PC DOS than Microsoft’s own product.

Word was spreading among computer buyers that Compaq DOS was better. Even people who owned other PC clones were choosing to buy that instead of Microsoft’s own public version. This could have created friction between Compaq and Microsoft. Instead, Canion did something extraordinary. Compaq withdrew Compaq DOS from sale unless it was specifically bundled with a Compaq computer. He then licensed Compaq DOS back to Microsoft.

From Gates’s perspective, this was an incredible deal. He was able to halt all internal development on Microsoft DOS, saving time and money. From this point onward, every version of Microsoft DOS he sold was, in fact, Compaq DOS, with the digital equivalent of its serial numbers filed off. All Canion asked in return was that Microsoft never release the very latest version of DOS that Compaq provided it until after a few months’ delay. This was to make sure that Compaq always had a slight advantage in compatibility over its rivals.

Canion even agreed to Gates’s request that they keep the entire arrangement secret, to avoid souring Microsoft’s relationships with the other clone companies. It would remain secret for almost 40 years.

Six years had passed since Canion and Gates made that deal. Since then, the relationship between Microsoft and Compaq had only grown stronger. So when Canion picked up the phone in 1988 and told Gates he was launching a rebellion against IBM, Gates listened. He even admitted that Microsoft had its own issues with IBM—particularly Lowe’s constant efforts to rewrite the licensing deal between the two companies so that IBM got a slice of the money Microsoft made selling DOS to the clones.

Despite these complaints, IBM remained Microsoft’s biggest client and—effectively—its patron. Gates’s company was built on its relationship with IBM, and it was already working with IBM on OS/2, a new operating system that would ship with IBM’s PC replacement. In that context, what Gates did next is extraordinary—a testament to the level of trust that had developed between Compaq, Microsoft, and the two companies’ founders. He committed Microsoft to Compaq’s rebellion, even though this risked IBM retaliating by ending all of their work with Microsoft.

Canion’s next call was to Intel. Compaq’s support with 386 chip development had earned both Canion and Compaq a lot of credit with Grove. Like Gates before him, Grove admitted that Intel had issues with IBM as well. Most notably, Lowe was threatening to break IBM’s relationship with Intel and use chips from IBM’s own chip plants in the new PS/2 instead. Grove trusted Canion, but he was worried. For this rebellion to work, the PC clones would need to create something that could match IBM’s Micro Channel in functionality, but be compatible with the existing standard. That would cost millions, and he couldn’t believe that they’d give that away for free.

Hugh Barnes was dispatched to show Intel’s engineers everything that Compaq had been working on since their all-hands meeting in January. They were astonished when Barnes handed it all over, without restriction. This show of trust, along with an offer to make Intel the exclusive supplier to Compaq for a number of chip designs, was enough for Grove. Intel were now part of the rebellion, too.

That rebellion would not work, though, if Compaq were the only PC clone company committed to it. Persuading others to join them was no easy task. These companies were Compaq’s direct rivals in the PC clone business, and many had reluctantly announced that they would license the PS/2 technology from IBM. Compaq had to persuade at least some of them to change their minds. That had to include Compaq’s biggest rival in the clone market—Hewlett Packard.

“If you're gonna get all the little players, you need the big players to start with. HP were the obvious one,” Canion said.

Bill Gates got them through the door at HP. He persuaded Robert Puette, general manager of HP’s PC division, that he needed to listen to what Compaq had to say. Puette agreed to a meeting, and Stimac and Swavely were dispatched in early May. Just as Barnes had done with IBM, Stimac and Swavely took with them full technical breakdowns of everything Compaq had been working on, and answered every question that HP’s engineers asked. This extraordinary level of trust got HP’s engineers onboard. Puette was slightly harder.

“There was a clear air of, ‘Well, IBM is out to kill us. How can we trust you? Won't you do the same thing?’” Canion remembered. “That guided our extreme openness. Such as going to an independent third-party law firm to manage the licensing.”

A few days later, Canion received a call. It was Puette. The HP man asked Canion to swear a personal oath that Compaq wouldn’t screw HP the same way they’d all been screwed by IBM.

“Absolutely,” Canion replied. That was it. HP was in.

After HP, Canion’s easy charm and reputation, combined with his ability to build consensus, brought almost all the other key players on board. By September 1988, Compaq had enough companies signed on to its rebellion to go public with it. In a testament to how respected both Compaq and Canion had become, IBM had no idea the rebellion was brewing. Not until Canion told Bill Lowe himself, just days before the planned announcement.

“We felt like if we were going to be fair... if we were going to be able to represent that we had offered it to everybody, it didn't feel right to say we offered it to everyone but IBM,” Canion said. “So we offered it to IBM.”

It was this that triggered Bill Lowe’s extraordinary offer on the phone to Canion, to open up the PS/2 to Compaq and split the market. Lowe wasn’t stupid. If he could split Compaq off, the rebellion would fall apart. Canion’s answer was simple and immediate.

No.

The ‘Gang of Nine’

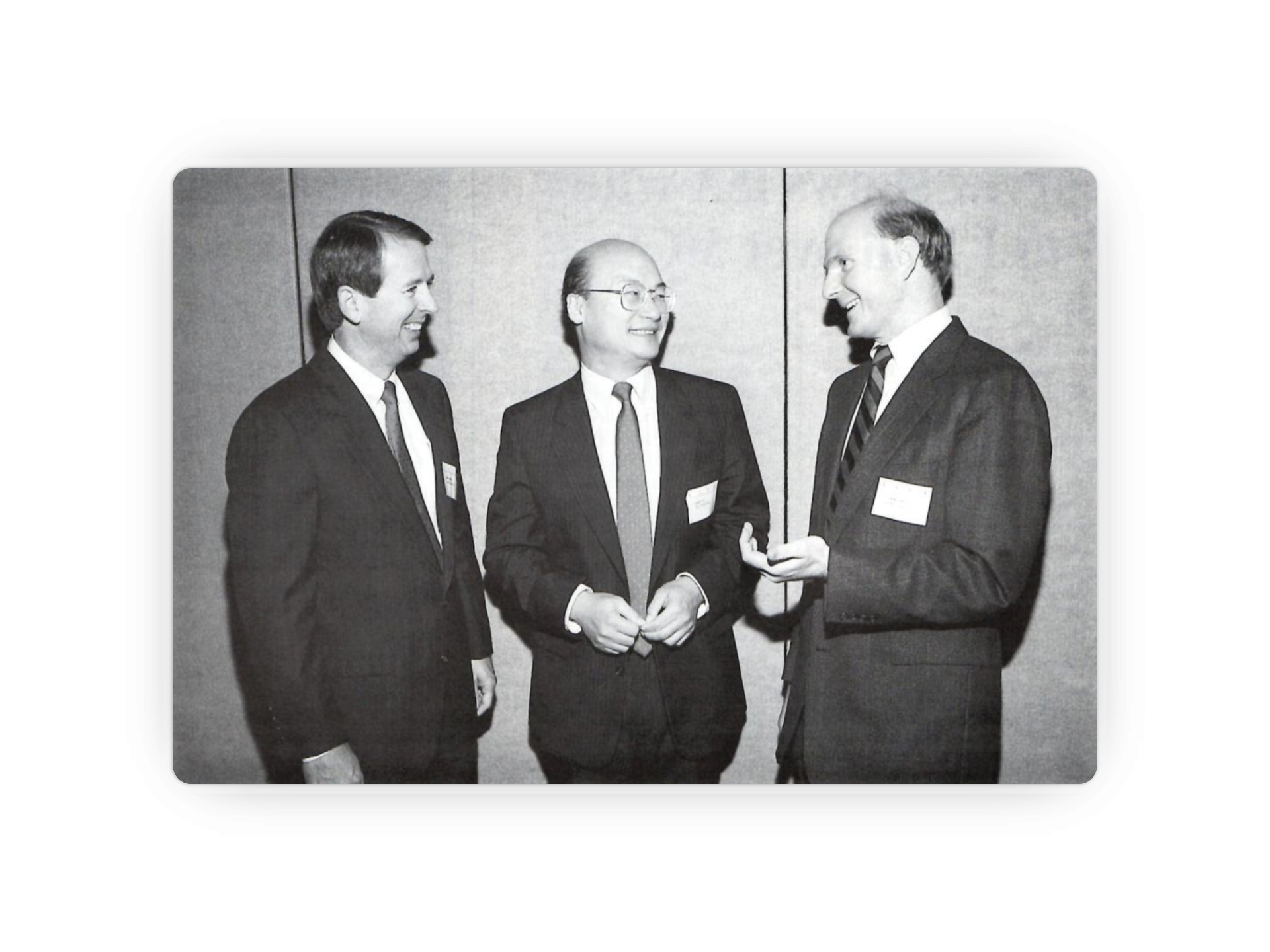

At 11 a.m. on September 13, 1988, at the Marriott Marquis in New York, Rod Canion announced the official creation of the Extended Industry Standard Architecture (EISA). He was flanked by eight CEOs from all the major players in the PC world—IBM excluded.

“With this EISA standard, we will work to maintain open, industry-standard PC platforms,” he declared.

Most investors and many in the computer press believed that IBM would still win out. Over the following months, that perception started to shift. Not least because Canion, the public spokesperson for the group that soon became known as the “Gang of Nine,” kept hammering home that the IBM PS/2 offered nothing that their own open standard didn’t already offer.

“Rod Canion publicly compared the PS/2 to Coca-Cola’s well-publicized marketing disaster, New Coke,” PC Week wrote in May 1987.

To the horror of IBM’s public relations department, it was an analogy that stuck, both in the computing and regular press. Slowly but surely, the momentum of the standards war began to swing behind the Gang of Nine.

That momentum depended on the Gang of Nine showing that their own standard could keep pace with anything IBM could offer. In reality, they needed access to the next generation of Intel’s chips as soon as possible—the 80486 (“486”). By March 1989, however, Hugh Barnes—now Compaq’s vice president of engineering—started to notice that Intel’s best chip people were being reassigned to other teams. Some quiet investigation revealed the cause. Sun Microsystems, one of Intel’s rivals, had announced chips based on a new design approach called reduced-instruction-set computing (RISC). For Intel, this presented a threat to its higher-end, large computer and mainframe markets. It was now shifting to focus on that threat instead.

At a hotel room in Silicon Valley, in April 1989, Canion and Gates met with Andy Grove and Intel chair Gordon Moore to try to persuade them to stick with 486 development. After considerable back and forth, Intel reversed course. The new chip launched in late 1989.

As it became increasingly clear that there was no technical benefit to the Micro Channel and PS/2, IBM tried one final time to deal a fatal blow to EISA, this time through the courts. It hit Compaq with a broad sweep of intellectual property lawsuits.

It was now that the years of effort Compaq had put into avoiding patent infringement paid off. IBM’s lawyers struggled to find anything major that would stick. To the delight of David Cabello, Compaq’s in-house intellectual property lawyer (himself a marker of how seriously the firm took its IP risk), the discovery process even revealed that IBM had accidentally infringed on a number of technical patents that Compaq held. At the end of 1989, Compaq and IBM agreed to a patent cross-licensing agreement that only cost Compaq a one-off fee of $130 million.

Into the future

By 1991 it was clear that Compaq—that Canion—had won. IBM’s efforts to regain full control of the PC market had failed. It was still pushing its proprietary PS/2 platform, but its market share was in rapid decline. Now that backward compatibility was something people expected by default—something IBM’s new machines didn’t offer—customers bought EISA machines from Compaq, HP, Dell, and others instead Especially now that backward compatibility was something people expected by default.

But the war had taken its toll on Compaq’s founders. Murto had retired in 1987 to spend more time with his family. That left Canion and Harris as the remaining founders. Friction over the way the company was run grew between Canion, now more than a little burnt out, and Ben Rosen, Compaq’s chair. Rosen believed Compaq needed to become leaner and more efficient; Canion believed Compaq’s strength lay in the culture and management approach that had carried it this far. When Rosen tried to elevate Eckhard Pfeiffer, one of Compaq’s vice presidents, to the role of co-CEO, Canion refused to accept it. Rosen called a board meeting.

“We were getting ready for a board meeting,” Harris remembered later, “and Rod said to me ‘Jim, they're gonna vote today on whether to remove me.’”

Rosen’s vote passed, elevating Pfeiffer and forcing Canion out. Harris immediately resigned.

“It was like the heart and soul of the company being torn out,” one Compaq employee said later.

“Looking back, it probably saved my life, the stress I was under,” Canion has since said. “I remember that as I left the company, I was sad but also relieved.”

Compaq would continue on without any of its founders. Under Pfeiffer, it would pivot more toward the low-end market. In 2002 it merged with Hewlett-Packard.

IBM gave up on the PS/2 in 1996. Its legacy would live on for a while in its ThinkPad series, but EISA had won. By failing to use it, IBM threw away its dominant position in the PC market. It would end up selling its entire PC arm to Lenovo in 2004.

"You could write a dystopian novel about what the PC world would be like if IBM won,” Canion says today.

True or not, the pace of technical progress would certainly have slowed if IBM’s “mainframe mafia” mentality had won out. The open and vibrant market of PC clones—like Compaq, Gateway, and Dell—would have constricted, and prices would not have fallen as fast. Those price drops eventually put a computer on every desk, opening the way for the explosion in gaming, internet access, and more. Even Commodore and Atari—the early masters of the home computer age—surrendered in the end, making PC clones before their final demise.

It was IBM’s Don Estridge whose vision created the open PC platform. But when IBM turned its back on that dream, it was Rod Canion at Compaq who saved it.

“There's no reason to assume somebody else would have done it if we hadn't. That’s true, I guess,” Canion admits. “Because there wasn't any other company or any other person... I mean, as the leader of Compaq? Yeah. I suppose I had to make this life-or-death decision for all of us.”

Keeping that dream alive required someone who could herd the various cats of the tech world, strong personalities and companies all. Someone they could all trust to put the interests of the collective ahead of himself.

Ask the man who beat IBM what makes him proudest about the multi-billion dollar company he founded, and it’s clear why he was one of the few who could do it.

“People still run into me today and say Compaq was the best place they ever worked,” Canion says, with a wistful look and a broad, Texan smile. “Why, that means a lot to me. It just makes my day.”

Gareth Edwards is a digital strategist, writer, and historian. He is an avid collector of old computers, rare books and interviews, and abandoned cats. Follow him on X, Mastodon, and BlueSky.

To read more essays like this, subscribe to Every, and follow us on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

We also build AI tools for readers like you. Automate repeat writing with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Deliver yourself from email with Cora.

We also do AI training, adoption, and innovation for companies. Work with us to bring AI into your organization.

Get paid for sharing Every with your friends. Join our referral program.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I was living and working in both Seattle and Mountain View during the early years this story was playing out. Learned DOS on my CompQ, CPM on my Osborne, and for a short while participated in introducing DEC’s Rainbow PC to the retail market. This essay brought back some amazing memories. Thanks.