Sponsored By: Napkin

This essay is brought to you by Napkin, the first app for intentional collection and mindful reflection on ideas. It magically connects them by topic, and curates flows of your ideas and insights, ensuring they remain fresh and continue to inspire you daily. Napkin is almost ready for the big launch.

Every subscribers get priority access to the Napkin beta.

I fucking hate free will debates.

They are the lowest-common-denominator of philosophical discussions. They reek of freshman-year philosophy majors, moldy marijuana, and the shallow profundity of Communist trust-fund babies. They are trite, heated, and mostly useless, like co-op board arguments over the color of the rug in the lobby.

I fucking love Robert Sapolsky, a Stanford neuroscientist whose books on biological behavior and stress, Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, A Primate’s Memoir, and Behave, are some of the best science writing I’ve ever read. He is, in my opinion, the poet laureate of neurobiology. He is at once rigorous and humanistic, sardonic and compassionate, literary and scientific.

So you must be able to imagine my conflicting feelings upon learning that he wrote a new book (yay!) about free will (yuck!) called Determined. It’s like Scott Alexander writing a 10,000-word essay on the correct way to hang toilet paper. It’s like Annie Dillard writing a new book on whether or not a hot dog is, in fact, a sandwich. It’s like Bill Simmons writing a trilogy about whether Die Hard is really a Christmas movie. (Okay, okay, I’d read that.)

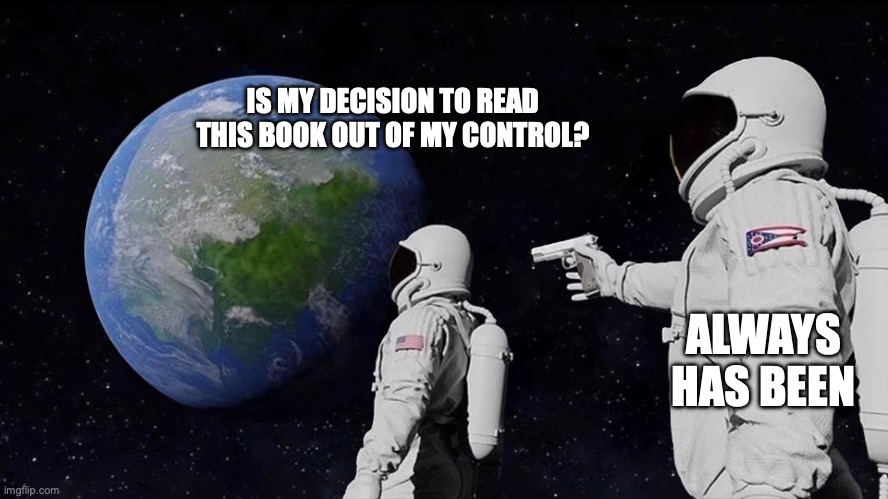

Despite my misgivings, I read an advance copy of the book. I read it in a single weekend and reread it again last week. And then I decided to write this review of it. (Freud would’ve had a field day analyzing the masochism in my reaction formation here.)

It is a book about why science says we have no free will, and how we might best live once we accept that. It is simultaneously moral, scientific, and compassionate. It is funny and irreverent. It is merciless in its attack on victim-blaming “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” philosophers. It contains the most magnificent and beautiful description of the anatomy of the sea slug that you will ever read.

Ever let a great idea slip away? With Napkin, that's a thing of the past. It's like having a digital extension of your mind, always ready to catch and cultivate your brightest thoughts. Napkin intelligently resurfaces ideas, stretching your memory to limitless bounds. Get inspired and unlock new levels of creativity.

Get early access to the most sophisticated thinking companion.

It is both a masterpiece and a missed opportunity.

Sapolsky’s argument is this:

You shouldn’t blame people for stealing or murder. Anger or retribution for evil acts is “indefensible.” No one deserves praise, money, or status for working hard or having grit or being “good.”

Why? The universe is deterministic: our choices are predetermined by the biology of our brains and bodies. Free will does not exist. Therefore, moral responsibility, whether we deserve blame or praise for our actions, does not make sense, and our whole system of ethics and justice should be reconsidered.

In other words, getting angry at someone for murder is as irrational as yelling at a hurricane. Locking people up should be a sober affair, driven only by their potential to do harm in the future and not as retribution for past offenses.

By the same token, hard work and good behavior are also a happy accident of our genes and our environment. The ability to work hard is just as much a product of luck as an attractive person’s face.

Sapolsky says that this is the only possible conclusion if you take seriously the biological evidence he is about to present. He takes pains to say that he is not presenting the partial view—that biology “sometimes” impinges on our behavior. Rather, all of our behavior is biologically determined; therefore, we have no control over it and are not morally responsible for our actions.

But then he also does something curious—he flinches:

“I haven’t believed in free will since adolescence, and it’s been a moral imperative for me to view humans without judgment or the belief that anyone deserves anything special, to live without a capacity for hatred or entitlement. And I just can’t do it. Sure, sometimes I can sort of get there, but it is rare that my immediate response to events aligns with what I think is the only acceptable way to understand human behavior; instead, I usually fail dismally.” [Emphasis mine]

That occurs on page 10 of a 500-page book. It’s a perfect encapsulation of why “disproving” free will seems such a fool’s errand. You’re telling me that I’m about to read a tome about the science of why we have no free will and its radical consequences for our ethical behavior—and though you’ve spent your life with these conclusions, you can’t get yourself to internalize and live by the argument?

This is why I hate free will debates. If an illusion is so strong that despite decades of effort you still act according to its dictates, you might be confused about what the word “illusion” means.It’s like saying the couch that I am writing this essay from is an illusion. That’s true—it’s in fact mostly empty space with a bunch of teeny tiny uncouch-like particles dancing a samba with each other beneath my butt—but I can still sit on it like it’s a couch.

After finishing the book, my conclusion is that Sapolsky is a mystic; he just hasn’t realized it yet. That’s why the book ultimately missed for me: He had the opportunity to connect the scientific insight he’s collected to a broad and deep tradition of individuals who have come to similar conclusions—and learned to experience and enact those conclusions. But he didn’t go there at all, rendering the book not actionable enough and therefore easily misinterpreted.

But it’s still an important read. Much of the way our lives are constructed depends on how much free will we think we have. Some of this is personal. If you’re beating yourself up for not working hard enough or for snacking too much, this is an important book. Likewise it is if you care about justice in the world—about how we habitually shame or incarcerate people for circumstances that are outside of their control.

So, in this review, I’ll give a brief overview of Sapolsky’s basic argument. I’ll then summarize what I think he’s missing. And finally, I’m going to write what I hoped the book might say.

Ready? Let’s go. We’ll start with Sapolsky’s basic argument.

'Free will doesn’t exist because we can’t find it anywhere'

Let’s say a man pulls the trigger of a gun and shoots someone.

Presumably, there is a set of neurons responsible for causing him to pull the trigger. In order to understand how that action occurred—how the muscles in his finger contracted—you’d have to understand the following:

- How the sights, sights, sounds, and smells the man experienced over the preceding seconds and minutes primed the neuronal action potentials in that man’s brain to squeeze the trigger

- How these neurons were influenced by whether the man was tired, hungry, stressed, or in pain at the time

- How the hormones in his brain over the proceeding hours to days changed his brain making them more likely to activate

- How any major catastrophic events over the previous months or years created the conditions for those circuits to form in his brain

- How his childhood experiences had affected his brain, particularly adverse events like losing a parent or being exposed to violence

- How the levels of hormones he was exposed to in the womb had affected his brain

- How his genes affected his brain structure (and how his childhood experiences affected the expression of those genes)

- How centuries of history and ecology shaped the culture he was raised in, and thus his brain

In other words, if you want to understand why a man pulls the trigger of a gun, you have to understand all of the preceding causes and conditions that gave rise to his brain in that particular state at that particular moment.

And if you examine that causal chain, you’ll find no room for free will anywhere. None of the elements of the chain that lead to the man pulling the trigger are directly under his control—it’s genes and environment all the way down.

To show this, Sapolsky performs a sort of free will-inspired Where’s Waldo? for the first half of the book. He examines how behaviors are generated in the brain. Then he asks: where is the free will? Is it here? No. Is it here? No.

The resulting text is a tour-de-force overview of everything we know about how biology produces behavior. And the conclusion he draws at the end is: because we didn’t find free will anywhere, it must not exist.

Let’s review the places he looks.

'Can we find free will inside of intent? No.'

Sapolsky starts by looking at “intent”—the experience of deciding to do something. He explains the studies that were first done in the 1980s by neuroscientist Benjamin Libet, in which scientists hooked subjects up to an EEG and asked them to “decide” to do something simple, like push a button.

These studies show that the brain activity signaling that you’re about to push the button arises about half a second before you’re consciously aware of making a decision. In other words, your subconscious hands a decision to your conscious mind, which then pretends like it decided to do the thing.

Studies like this have been debated for 40 years. They’ve been consistently replicated. But there are also a lot of holes. They concern relatively simple physical actions (like button pushing) that are done spontaneously; it’s possible other kinds of decisions happen differently. They also aren’t very predictive: if a researcher uses an fMRI to scan your brain, they can only determine with 60 percent accuracy which button you’re going to press before you’re consciously aware of your decision.

The studies don’t conclusively prove that free will doesn’t exist. But the body of evidence does cast a significant pall over the idea that intent is where free will arises. Why? Even if you do think that somehow intent escapes Libet unscathed—in other words, conscious choices do exist—you’d still have to ask: where does that intent come from? And then you get stuck back at the same causal chain: immediate situation, prior days and months, childhood development, fetal development, genetic makeup, cultural environment, going all the way back to when we were slimy amoebas oozing around like gefilte fish in primordial broth.

'Can we find free will inside of our ability to make choices? No.'

The obvious counter to this is: can’t you just make different choices? Can’t someone just change their intent? Sapolsky’s answer is no. To prove it, let’s walk through the timeline of influences on our shooter and how they are all out of his control:

Seconds to minutes before the trigger pull: If there’s a disgusting smell in the room, he might be more likely to pull the trigger (page 48). That’s because the brain center, the insula, that governs our sense of disgust activates for both biological disgust (e.g., rotten food) and moral disgust. If he believes he’s doing something moral by shooting, the gross smell might make it more likely to happen.

Minutes to days before: If testosterone is elevated at the crucial moment when he’s deciding whether to pull the trigger, he’ll be more likely to perceive threat and less empathetic than he would be otherwise. Testosterone levels change for many reasons, like time of day, your health, or when you last had sex—all outside of his control.

(There are other hormones that can have similar or offsetting effects—for example, oxytocin makes us more prosocial but only to people we consider part of the “in” group. If his oxytocin level is activated, he’ll be more cuddly with his friends and might be more likely to pull the trigger if he perceives his target to be part of the out-group.)

Weeks to years before: If the man has been barely managing to pay his rent for years, or is suffering from depression, or has been in a happy marriage for a decade—all of those things will change the structure of his brain. His altered brain structure will modify what he perceives as a threat and how he weighs the consequences of his actions. This is enough to change whether or not he pulls the trigger.

Childhood: If the man experienced a lot of stress in childhood, he’ll likely have trouble with impulse control later in life. Chronic stress impaired his frontal cortex, and no matter how badly he wants to master his impulse to pull the trigger, he may be structurally unable to. Indeed, “a substantial percentage of people incarcerated for violent crime have a history of concussive head trauma to the PFC.” (page 99)

“OK, all of this is true,” you might say. But this guy’s clearly a deadbeat. If he’d worked a little bit harder, or applied himself in school or at his job, or not gotten addicted to drugs, then he wouldn’t be where is holding a gun.

He should’ve just worked harder to avoid this situation, right? Sapolsky addresses this, too.

'Can’t we find free will inside of our ability to work hard and apply willpower? No.'

Hard work and willpower are also biological.

You can’t will yourself to have more willpower. Willpower is a function of the brain that is connected to the same causal chain that the rest of your brain is connected to. It’s a finite resource that is determined by your genetics and your previous experiences. You can exert willpower to some degree—but how much willpower you possess is out of your control.

The same is true of hard work. It’s just as much a product of your genes and your environment as anything else. It’s more difficult to work hard, for example, if you grew up in a violent household, or if you are malnourished or have experienced certain kinds of head trauma.

If we want to save free will, we need to look somewhere else.

'Can we find free will in some other place then? Like emergence or quantum indeterminancy?'

The last place people tend to look for free will is in weird ideas in physics and philosophy, like emergence and quantum indeterminancy. Emergence is the idea that complex systems like brains are not reducible to their constituent parts; complex behaviors emerge that are unpredictable from the raw biological substrate. (Individual neurons aren't conscious, but brains are, and consciousness emerges from the electrical activity between neurons.) Sapolsky doesn’t think you can find free will here because, ultimately, every behavior is reducible to neurons firing in different ways.

Other thinkers try to locate free will in quantum indeterminancy, the idea that we can never precisely predict the properties of the particles in the universe. There will always be randomness. Therefore, we’ll never be able to fully predict behavior.

But, in Sapolsky’s view, that doesn’t save free will. Just because something is random doesn’t mean it was freely decided—just that it wasn’t predictable beforehand.

This completes Sapolsky’s search for free will—and he thinks it’s nowhere to be found. He then begins to examine what that might mean.

How should we act in a world without free will?

In 1487, a couple of Dominican friars published a book called Malleus Maleficarum, which claimed that anyone who had seizures was a witch possessed by the devil. Not only that, but they had become a witch because of their free choice—they had decided to welcome the devil, and their seizures were the consequence. Unsurprisingly, many people who didn't worship the devil—but who did suffer from medical conditions that caused seizures—were killed as a result. More generally, for thousands of years, people with seizures have been avoided, feared, and mistreated because of their condition.

Today, we don’t feel that way. If you have a seizure while you’re driving and accidentally kill someone, you’re not held morally or legally responsible. We know that you are not in control of your seizures. The march of science has taken something that we used to see as “freely chosen” and turned it into a mere function of our biology. As a result, we treat people more compassionately, avoid blaming the victim, and deal with root causes instead of hewing to superstitions.

Sapolsky argues that, as we get more familiar with how the brain actually works, this pattern will hold true for all of our behavior, good and bad—from hard work to theft or murder. We’ll be less likely to think of it as something freely chosen and deserving of blame or praise, and more like having a seizure. Each of the behaviors is driven by the way our biology has interacted with circumstance—not freely chosen:

“This multicentury arc of the changing perception of epilepsy is a model for what we have to do going forward. Once, having a seizure was steeped in the perception of agency, autonomy, and freely choosing to join Satan’s minions. Now we effortlessly accept that none of those terms make sense. And the sky hasn’t fallen.” (page 316)

In this world, he argues that we might still have something like prisons to house those who commit crimes. We might still decide to separate a murderer from the rest of society. But we wouldn’t do it in anger, and we wouldn’t do it as retribution. We’d do it, Sapolsky argues, “the absolute minimum amount needed to protect everyone, and not an inch more.” (page 349) He thinks a model like this would work purely on “forward-looking proportionality, where the more danger is posed in the future, the more constraints are needed.” (page 351) He thinks this is better than our current justice system, which is backward-looking. (Having just spent several hundred pages reading about how our future behavior is dependent on our past, I have a hard time knowing what the difference would be.)

Sapolsky believes that doing away with our conceptions of free will and moral responsibility is both possible and compassionate. It will bring about a better world where people are neither left to be the victims of circumstance nor blamed for the ways in which their biology hinders them.

Sapolsky spends the end of the book musing about the consequences of believing in determinism and rejecting free will. He examines and rejects the possibility that holding these two beliefs might cause us to be immoral or apathetic.

Instead, he believes that they should cause us to be more moral and make better choices—knowing the contingency of our circumstances.

Now let me tell you what I think

Sapolsky’s argument can be summed up like this: “We are beings caught in an unbroken chain of causes that dictate our choices. We lack free will and are wholly subject to circumstance. Therefore, we should choose to be better to each other.”

This is a contradiction.

If you accept determinism and a lack of free will, and then change your decisions in any way, you’ve negated the argument. The moment you decide to forgive a murderer because free will is an illusion, you’ve affirmed your ability to make choices and, therefore, your belief in free will.

Sapolsky seems to skim over the fact that determinism operates regardless of our belief in it. Our lack of free will operates in the same way. It’s an inescapable cosmic backdrop that is present whether or not you get up in the morning, whether or not you read philosophy books, whether or not your hands are tied behind your back, or whether or not you are in love, or grieving, or sick, or tired.

The infinite chain of causes that Sapolsky refers to in order to explain our behavior shows us that we’re just a temporary arrangement of particles—an eddy in a stream, a pattern of the wind—subjected to and determined by everything that has ever come before us. It is beautiful. It shows that we are all connected. Nothing and no one is separate. Nothing escapes.

But the minute you refer to this chain and use it to justify your actions, you are no longer talking about this larger truth. Instead, you’re affirming your own free will and personal control. You are, from your own perspective, making a free choice—and you’re doing so because you know that choices matter. That’s the weird paradox at play here.

Determinism and biological insight can explain certain behaviors at certain times. It is profoundly moral to raise awareness of the ways in which biology and circumstance leave people with no control.

But doing this preserves—not negates—agency. When we attribute someone's seizures to biology, we're not dismissing their agency wholesale; we're merely relocating it to other aspects of their lives where deterministic explanations haven't yet been applied or understood. In fact, relocation only becomes possible once we gain the scientific understanding to control those seizures. So even in acknowledging the deterministic nature of some behaviors, we're paradoxically affirming our agency to understand and manipulate them.

It’s problematic when we try to ascribe all behaviors to this causal chain. It has to be approached from a different angle—as poetry rather than prose. The Tao that can be named is not the eternal Tao.

The true value in examining the deterministic causal chain that gives rise to our behavior is that it fosters compassion. We are all being borne along by a wave of causes and conditions that are always at work no matter what we do. We are part of a broader fabric of reality that we cannot escape. Yet we still see ourselves as agents who are able to make choices. There is no other way to live.

The world is deterministic. There’s free will (and there is no free will). Moral responsibility exists (and it does not exist). This is mystical insight arrived at through science.

Sapolsky is mistaken in not connecting his conclusions to the various mystical traditions that espouse the same idea. For example, for thousands of years Buddhism has taught about dependent origination: everything that occurs is dependent on causes and conditions; nothing is separate.

Or in the Bhagavad Gita from the Hindu tradition: “One believes he is the slayer, another believes he is the slain. Both are ignorant; there is neither slayer nor slain… They live in wisdom who see themselves in all and all in them.”

Determined is a work of genius that is also a miss because mystical traditions have developed ways of integrating and operationalizing this insight into daily life. They understand it as a way to foster compassion, a different way of relating to the world around you. And they’ve developed techniques to make this insight alive and present. Experienced meditators often talk about the “self” as an illusion—another way of saying that they’ve glimpsed the ways in which their behaviors are the result of causes and conditions outside of their control.

I think Sapolsky misses all of this because he’s inherently suspicious of religion. But there’s nothing supernatural or superstitious about these kinds of experiences. That’s why he’s come to the same conclusions after decades of being a scientist.

It’s okay, I still love him.

. . .

Phew. So ends the piece I didn’t want to write and the argument about free will that I didn’t want to have. What can I say—I almost had to write it.

It felt like I didn’t have a choice.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Hey Dan! As always, loved your writing! However, I disagree with the first argument you make against free will.

“If you accept determinism and a lack of free will, and then change your decisions in any way, you’ve negated the argument. The moment you decide to forgive a murderer because free will is an illusion, you’ve affirmed your ability to make choices and, therefore, your belief in free will.”

Is this really the case? Is one not merely making a choice at this time? A different one than previously made, but a choice nonetheless. Who says that this new choice is not determined by our biology? The nature (biology) and nurture (environment/experiences) would influence whether they are more or less likely to change their choices, i.e., their ability to be flexible.

I tend to think in a way that aligns with Sapolsky (and compassion). However, I agree that philosophically free will or the lack thereof is hard to argue about. Particularly, because either point is non-falsifiable.

Best,

Arushi

Dan. Loved this. Sam Harris is obsessed with this notion. And his Waking Up app which teaches Buddhist Vipassana aka Insight meditation lets you explore the free will illusion during meditation. I recommend. Although once I did it, I kind of gave up all my pursuits and became a lazy ass for a while. It’s easy to get into a what’s the point mentality. Sam says free will is no doubt an illusion but that choices matter. A paradox I can’t wrap my head around. Of course I want to make the best possible choices. But how on earth do I have control over those choices? Mindfulness Meditation is advertised as helping you make more skilled choices. More compassionate choices. I am a long time consistent practitioner and I have seen myself able to pause watch my biological reaction then react from a “higher” more “compassionate” place. But that was not me doing it. It’s simply causal and conditional phenomena. What the heck am I supposed to do with that? Haha. Where I have landed is to try to surround myself with as much wise insightful inspirational and deep media and people. So that good mojo causes and conditions keep coming my way. Then the world is pushing “me” toward those wise compassionate realms. You are part of that media plan, Dan! Keep it up!!!