About a month ago I got a DM inviting me to “a community for casual, drop-in audio conversations.” So I downloaded the app, created a profile, and was greeted by a blank screen.

Uhhhh...

Then, a face appeared! Its name was Paul — and it spoke!

“Hey! Welcome!”

After we exchanged pleasantries, Paul explained how the app works. There’s one global “room,” and when you join you start off on mute, but anyone can unmute themselves. When you open the app, it sends push notifications to everyone on the app, so they can join you and chat if they’re free.

Strange, but delightful!

We said our goodbyes, and the app shrank into its place, like a genie sucked back into a bottle. The icon was a black and white photo of a guy with a funny grin, for some reason. Beneath it was the name:

“Clubhouse”

. . .

If your corner of Twitter is anything like mine, you’ve seen a lot of talk about Clubhouse in the past weeks.

The reactions are, like many things these days, polarized and overly meta:

- Some people LOVE IT because it’s the first exciting new social app they’ve seen in years, and they miss the good old days when the internet felt fresh and full of possibility.

- Other people HATE IT because it’s become known as an invite-only “elite silicon valley” thing. (To be fair, the founders want to open it to everyone as soon as possible, and anyone in the beta would testify it’s definitely not ready for scale yet.)

- Some people love to let you know they’re in it, because they think it makes them look cool. (Oh shit is that me?)

- And finally, some people love to let you know that they know the only reason people talk about Clubhouse is because they think it makes them look cool, because they think that makes them look cool. (Get it?)

But honestly, I’m not interested in the chatter. I’m interested in the product, and its potential as a business.

So let’s focus on that.

. . .

Social apps are just like any other product. In order to understand their probability of success, you analyze them the same way you would anything else:

- What need does it fulfill?

- How does it compare to the alternatives?

- Why should it emerge now, of all times?

- Who is paying, and why?

- What’s the accumulating competitive advantage?

If those add up, you might have a valuable thing on your hands.

In this essay, I’ll quickly tackle each of these questions in order to understand why Clubhouse is doing so well now, and how far out we can reasonably extrapolate their initial traction.

Then, I’ll focus on friction in the current Clubhouse experience, and suggest a few ideas for what I would do next if I were the founders.

(And after that, as a bonus, I’ll pitch Jack Dorsey and Daniel Ek on why they should try to buy this app — but not immediately!)

. . .

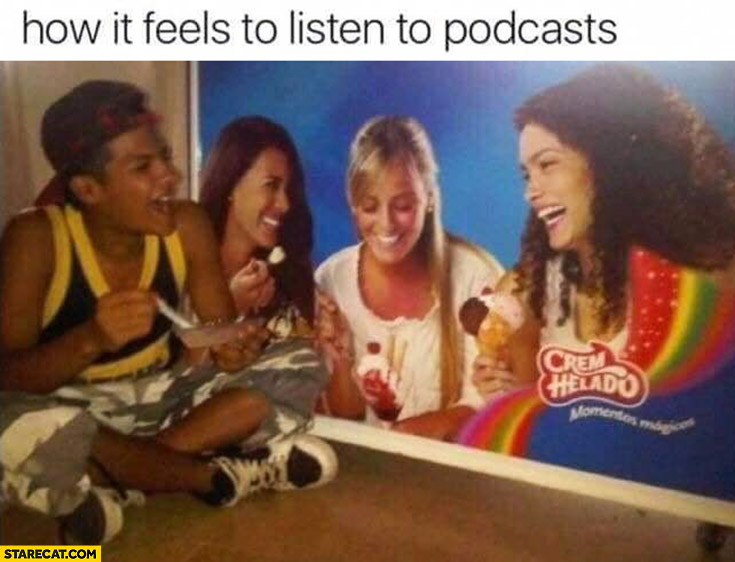

Clubhouse is working because it’s halfway between a podcast and a party, and people love both of those things.

The great thing about podcasts is they allow you to learn how your heroes think and see the world. The more you listen, the more you become like them. You start to know the things they know, think the way they think, and talk the way they talk — right down to the verbal tics.

This is more important than it may seem. Research has shown that humans aren’t that much better than other intelligent creatures at first-principles reasoning, but we are absolute killers when it comes to “monkey-see-monkey-do.” (The formal term for this is “social learning.”)

“But most people aren’t interested in learning!” You might say. And it’s true, the popularity of lifestyle, gaming, comedy, and sports vastly exceeds the kind of nerdy stuff that you and I get excited about. But it’s also wrong, because if you’ve spent any time on TikTok or Twitch or YouTube, you’d know that the reason people are there is absolutely because they want to learn. It’s just that instead of learning about business strategy, they’re there to learn far more practical skills, like how to dress, and how to respond when someone pokes fun at you, and what certain cool references mean. Those skills are way more obviously useful than anything you’ll learn on nerdy newsletters like this 😂

Of course, live audio conversations aren’t the only way to socially learn. Text and video are great, too. But unscripted conversations have unique competitive advantages that are unbeatable in certain scenarios.

As is well known, audio is better than writing and video when you need your eyes for something else, like driving or cooking. (Lately I’ve been loving Clubhouse while I tend a fire for the BBQ I’ve been smoking on the weekends.) Another great thing about audio is it’s a much better medium for conversation than any other, because video of talking heads gets boring after a few minutes, and interview transcripts are often hard to follow. Audio also enables people to create without worrying about how they or their environment looks.

But why live audio? Why show a list of everyone who’s listening? Why allow listeners to become speakers? These are the things that make Clubhouse distinct from podcasts — more like a party — and they’re built into the product for several good reasons.

First, live audio enables a uniquely efficient form of social learning. When you can see a person responding to new information on the fly, it’s easier to piece together the deeper patterns that govern their thinking. When they’re in an environment that’s not perfectly controlled and edited — like an essay — it’s easier to mask shallow understanding. “Live” takes the spontaneity of a podcast and cranks it to eleven.

Second, and more importantly, on Clubhouse you can meet great people. And that is one of the deepest desires in our hearts. People need each other. But there are so many things that pull us apart. Creating an environment that makes this happen is hard, but incredibly valuable when it works. It’s fascinating to me how some Clubhouse rooms feel like a bunch of kids joking around in the back of the bus, and others feel like a lecture hall. Both can be valuable depending on the circumstance.

This is also an area where Clubhouse is subtly but hugely different from live video apps like Periscope. By default, the content is co-created with a small group. Listening to a conversation from a handful of people is so much more compelling than watching a video from one or maybe two people. It’s also the key to the “party” dynamic — meeting people.

How do you meet people on Clubhouse? You join a room where you know people, and raise your hand to speak, or are invited to. This simple mechanic makes a huge difference. It’s the core “grind” of Clubhouse. And it solves one of the biggest problems with podcasting:

To explain how valuable it can be to break through the metaphorical wall between speaker and listener, let me tell you a story from my own experience using Clubhouse.

One afternoon I got a push notification saying that Paul was talking to Naval Ravikant. If this was a podcast, I would think “hey that’s interesting, maybe I’ll listen later.” I would probably read the episode title and show notes, and I would consider whether the topics were interesting to me, and maybe I’d listen, or maybe I would save it for later.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!