If you want to understand how AI progress will unfold over the coming decade, a good historical analogy is the cat-and-mouse dynamic that ruled the PC industry in the 1980s and ’90s.

Back then, computers were good enough to attract millions of users, but their limited speed and storage were often a pain. Demand for increased performance was enormous. But just as soon as new generations of more powerful computers were released, developers quickly built applications that took advantage of the new capacity and made computers feel slow and space-constrained all over again, fueling demand for the next generation of improvements.

The main bottleneck was the central processing unit (CPU). Everything a computer does has to flow through it, so if it’s overloaded, everything feels slow. Therefore, whoever made the fastest CPUs had an extremely desirable asset and could charge a premium for it.

Intel was the dominant player. Its ecosystem of compatible devices, library of patents, integration of design and manufacturing, economies of scale, partnerships, and brand recognition (even among consumers!) all came together to make it the largest and most profitable supplier of CPUs in the ’90s. It is hard to overstate Intel’s dominance—it maintained 80–90% market share through this whole era. It took the platform shift to mobile, where battery efficiency suddenly mattered, for their Goliath status to unwind. [1]

Today we are seeing the emergence of a new kind of “central processor” that defines performance for a wide variety of applications. But instead of performing simple, deterministic operations on 1’s and 0’s, these new processors take natural language (and now images) as their input and perform intelligent probabilistic reasoning, returning text as an output.

Like CPUs, they serve as the central “brain” for a growing variety of tasks. Crucially, their performance is good enough to attract millions of users, but their current flaws are so pronounced that improvements are desperately demanded. Every time a new model comes out, developers take advantage of new capabilities and push the system to the limits again, fueling demand for the next generation of improvements.

Of course, the new central processors I’m talking about are LLMs (large language models). Today’s dominant LLM supplier is OpenAI. It released its newest model, GPT-4, yesterday, and it surpassed all previous benchmarks of performance. But developers and users are still hungry for more.

Although LLMs have a lot in common spiritually with CPUs, it’s too early to know whether the LLM business will be as profitable or defensible as the CPU business has been. Competition is coming for OpenAI. If it falters, that wouldn’t be the first time the pioneer of a complex new technology ended up losing market share.

Case study: Intel’s memory failure

Once again, we can look to Intel’s past to glean insight into OpenAI’s future. The early years at Intel represent a cautionary tale of commodification. Because Intel was the dominant supplier of CPUs in the ’80s, ’90s, and early 2000s, it’s easy to forget it actually started out in the RAM memory business, and even helped create the market in the 1970s. Its superior technology and design enabled it to capture the market in the early years, but as time went on, it had trouble staying competitive in the RAM market.

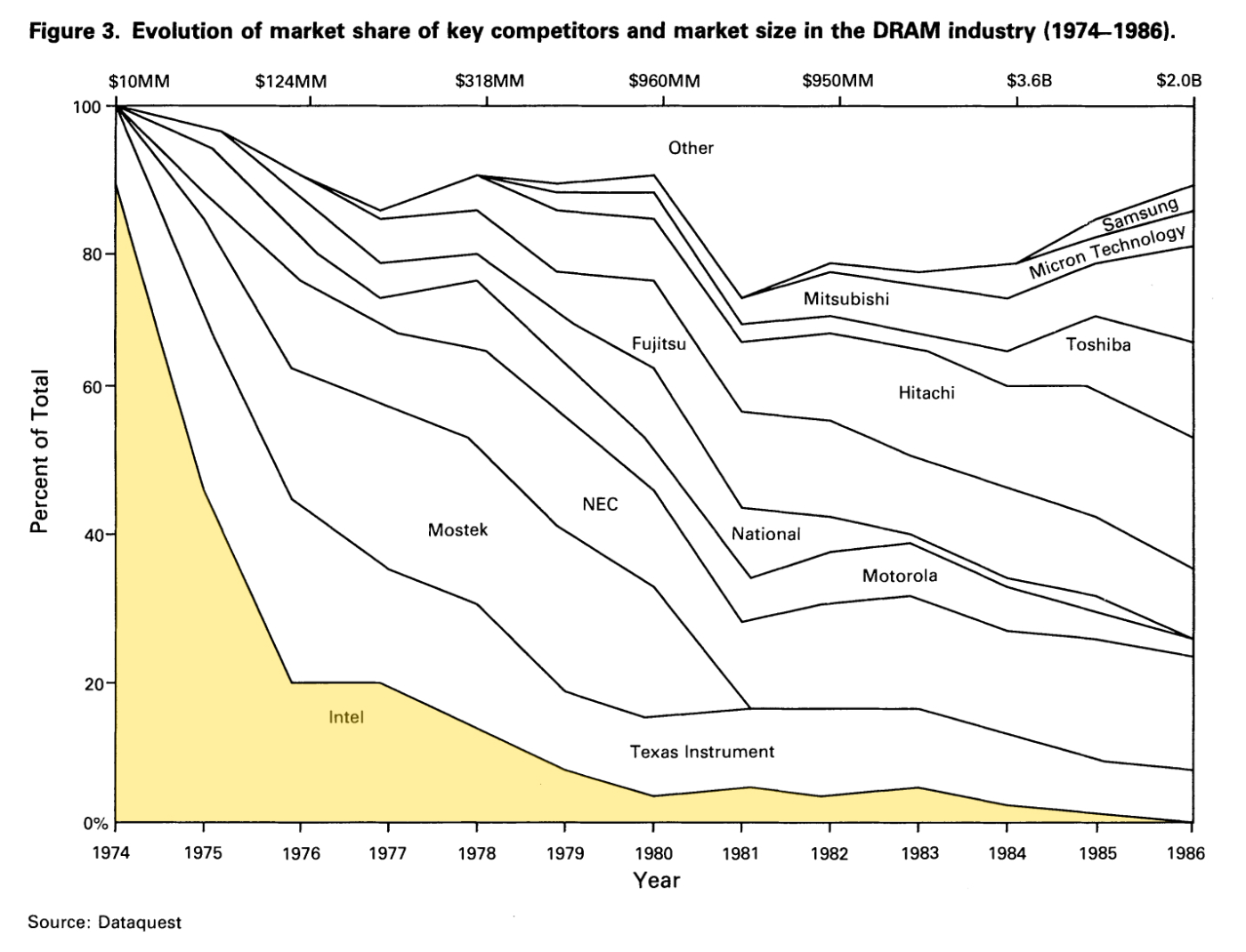

Just check out the brutal drop in Intel’s market share (highlighted in yellow):

Caption: The following chart and analysis come from this excellent paper, which is based on interviews with dozens of key executives at Intel.

What happened? The basis of competition shifted. In the early days of the memory industry, the most important thing to get right was the chip design. Intel won by having the best engineering talent. But as the years went on, manufacturing efficiency started to matter more. The basic architecture of RAM memory became more standardized, and many firms learned how to make it, so the winners became the ones who could build new memory chips faster and more efficiently, with higher yields. Intel’s talent lay in chip design, not manufacturing processes.

Intel soon found that the CPU business was a better fit for their capabilities. Manufacturing efficiency was relatively less important here, while design and performance mattered more. CPUs are a much more complex technology, and require deeper integration into customers’ products. Once you design your computer around a CPU architecture, it becomes a huge pain to switch. Intel won the market by demonstrating to customers that it was shipping ever more capable chips each year, which you could upgrade to with minimal pain. Customers wanted to bet on the team that would deliver the most performance over time for the least upgrade cost, and so an ecosystem started to grow around Intel products.

Mapping Intel’s lessons onto the LLM market

As Intel learned the hard way, CPUs were a differentiated product, while computer memory became a commodity. So, in the emerging AI world, what bucket will LLMs fall into?

In some ways, they’re a lot like CPUs. As I said in the intro to this essay, from a functional perspective they’re the central “brain” that will power most new intelligent software features. Also, performance is currently not good enough and it’s the key bottleneck to making overall AI product quality better, so developers and users have massive demand for improvements.

But LLMs are also similar to RAM in crucial ways. Despite having vast internal complexity, the interface between the LLM and the application it’s integrated into couldn’t be more simple: text in, text out. (Ok, the newest LLMs can take in text and images now, but the interface is still very simple and the point stands.) Unlike CPUs, it’s very easy to swap one LLM out for another. You have to change only one line of code if you use a framework like LangChain. And the cost of using an LLM is still prohibitively high for many applications, so the competitive pressure to get more efficient at scale and bring costs down is very real.

When I consider these reasons, I can’t help but conclude that LLMs, despite their spiritual similarity to CPUs, will have economics that more closely resemble the memory business. If I’m right, this could be bad news for OpenAI.

The key point is the lack of switching costs. This is great for application developers, but not great for LLM providers. In technology tools, when switching costs are high, ecosystems tend to grow around them. Look at JavaScript frameworks, for example. If you write your code using ReactJS, you’re probably not going to switch to Vue unless you’re building an entirely new product. Also, if you want to build a plugin or library, it’s usually double the work to make it interoperable with multiple frameworks. This causes a sort of switching-cost-induced network effect, where people only build libraries to work with the most popular frameworks. That in turn results in a “winner take all” dynamic.

It’s still early, but I’m not seeing signs that a similar dynamic will play out with LLMs. They are more like cloud storage providers. If I wanted to host my application’s images on Microsoft Azure instead of Amazon S3, it would be a relatively simple change. For now, LLMs are even easier to swap out, because they don’t save any state or data.

There aren’t many developer tools built around LLMs yet, but those that do exist are almost all “provider agnostic”—they operate on the assumption that applications may change models frequently or even use multiple models to accomplish specific tasks. All of this is made possible because the “text in, text out” interface is so simple.

Is there some way that the interface could become more complex in the future, increasing switching costs? It seems unlikely. Of course, it’s easy to build a complex interface—the hard part is getting developers to adopt it. Simpler is always preferred. The reason why people adopt tools with complex interfaces (like Intel’s x86 instruction set, or React’s JavaScript API) is because there is irreducible complexity in the task they are trying to accomplish. In fact, the tools that win often do so because they were able to make a complex thing feel more simple. I know from firsthand experience this is a big reason why React won, and the paper about Intel mentions it as an important cause of its success.

The one thing I do think could change the dynamic entirely is if OpenAI (or one of its competitors) decided to open source their models. It may seem like they would have less power if they did this, but I believe they’d actually have more. It is significantly more complex to run your own LLM instance, and to customize it, than to just use a simple web API, so the switching costs are higher. Also, the only people who would actually bother to do this are larger organizations with specific privacy and customization needs, so that’s an attractive customer base to embed yourself in anyway. You’d perhaps lose some money you’d otherwise gain by operating a hosted LLM service, but you’d also open up new lines of revenue around customer service and consulting.

But for now, the best models are only available via API. Let’s assume for a moment that it stays that way. Is there some other way for OpenAI to generate a network effect? Some would argue its direct connection with users via ChatGPT helps, because it gives OpenAI proprietary training data, but it’s unclear if this will result in anything other than marginal gains in LLM quality. I will be watching this closely, but my gut says it won’t matter that much.

What this means for you

For developers, it’s a great time to be building applications powered by LLMs. Right now it may feel like the only game in town is OpenAI, but I doubt this will last for long. It is an important company, but once there are one or two reasonable substitutes, the pricing should come down. Then, the basis of competition will likely shift to efficiency at scale, like it did for the memory business and cloud computing.

For OpenAI, success will increasingly hinge on those factors, and developing new, high-quality models won’t be the only thing that matters, as it has in the past. Microsoft Azure will be (and is) a crucial partner here, because they have the resources and expertise to help OpenAI scale. This isn’t a future prediction, it’s a description of what matters today. This is why the new ChatGPT API is 10x cheaper than the previous GPT-3 API, and why it makes sense for engineers from OpenAI and Microsoft to collaborate on building custom chips and infrastructure to run these models.

For OpenAI’s competitors, the name of the game is still catch-up. No model I have seen can approach GPT-3 (let alone GPT-4) in real-world performance yet. Until this happens, any focus on efficiency doesn’t matter. My prediction is that this will continue for maybe a year or two, and then increasingly the knowledge will diffuse and there will be multiple high-quality providers.

I will be very interested to see what comes from Google, which supposedly has the world’s best models locked in a closet in Mountain View. Perhaps it will release them soon? I’m also interested in Stability AI, the makers of Stable Diffusion, which is rumored to be building an open source LLM. Anthropic announced Claude yesterday, and it is early but compelling—worth keeping an eye on.

The point is, the landscape is changing, and it’s going to be exciting to watch it unfold over the coming months and years. LLMs will become more than just another API service; they will become a cornerstone of modern computing, with an impact similar to that of the CPU.

If you ever wished you were around at the beginning of the internet, or in the early days of the PC industry, congrats! You’re here now for something just as important.

—

[1] If you’re wondering why Intel struggled to make battery-efficient CPUs, this footnote is for you! It’s a super-interesting question. In Intel’s entire history of making CPUs, it never had to worry much about energy efficiency, since the machines they were designed to be used in were mostly sitting on a desk, plugged in. Turns out, this is a hard switch to make. The chip architecture that mobile device manufacturers turned to (ARM) had a totally different design philosophy than Intel’s. Instead of one power-hungry black box, it was actually more of a toolkit that could be heavily customized. This is important because in order to optimize overall performance and battery life, you need a lot more control over the CPU than what Intel was designed to offer. Now you know!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Hi Nathan,

I do agree LLMs are becoming the new focal point for computing. But I don't think the memory analogy is apt. As you note, memory is a fully fungible component. When buying from Intel, TI, Samsung etc, you are buying a product with equivalent performance for a given specification. There is no qualitative difference. But for LLMs, each model outputs very different things. Swapping one for another immediately produces tangible effects. It's more like a Coke and Pepsi situation - you can taste the difference! And given that the product spec is entirely open ended and infinite in scope, I don't think it's even possible to produce a spec equivalent LLM. Talent, data, data processing, training/inference infra, distribution (via MSFT) are immense tailwinds that will produce product differentiation that's very tangible and lasting.

It's not a given that 'best models' will continue to be accessed via API, especially if you include cost. Since LLMs can train other LLMs, machine IQ can be effectively photocopied.

https://www.artisana.ai/articles/leaked-google-memo-claiming-we-have-no-moat-and-neither-does-openai-shakes