A couple days ago I had a chat with an executive in media about the bundling strategy at Everything. The executive said a lot of interesting things on that call, but there was one phrase that particularly piqued my interest:

“The Competitive Exclusion Principle”

At one point, I was explaining how a goal at Everything is to fund people to write essays of greater depth and polish than is possible if they had to publish weekly, and that maybe this could be a compounding advantage for us — the bigger we get, the more we can invest in great writing and thinking, the more subscribers we attract, the more we can invest, the harder it might become for lower-cost writing to compete. He nodded his head and said, “Ah, yes, the competitive exclusion principle!” He said it a couple of times like this, and in each instance my ears pricked up.

I had no idea what it meant, but it sounded juicy. So that night I did a bit of digging.

(Normally I’d just ask, but we had very little time, okay?? 😆)

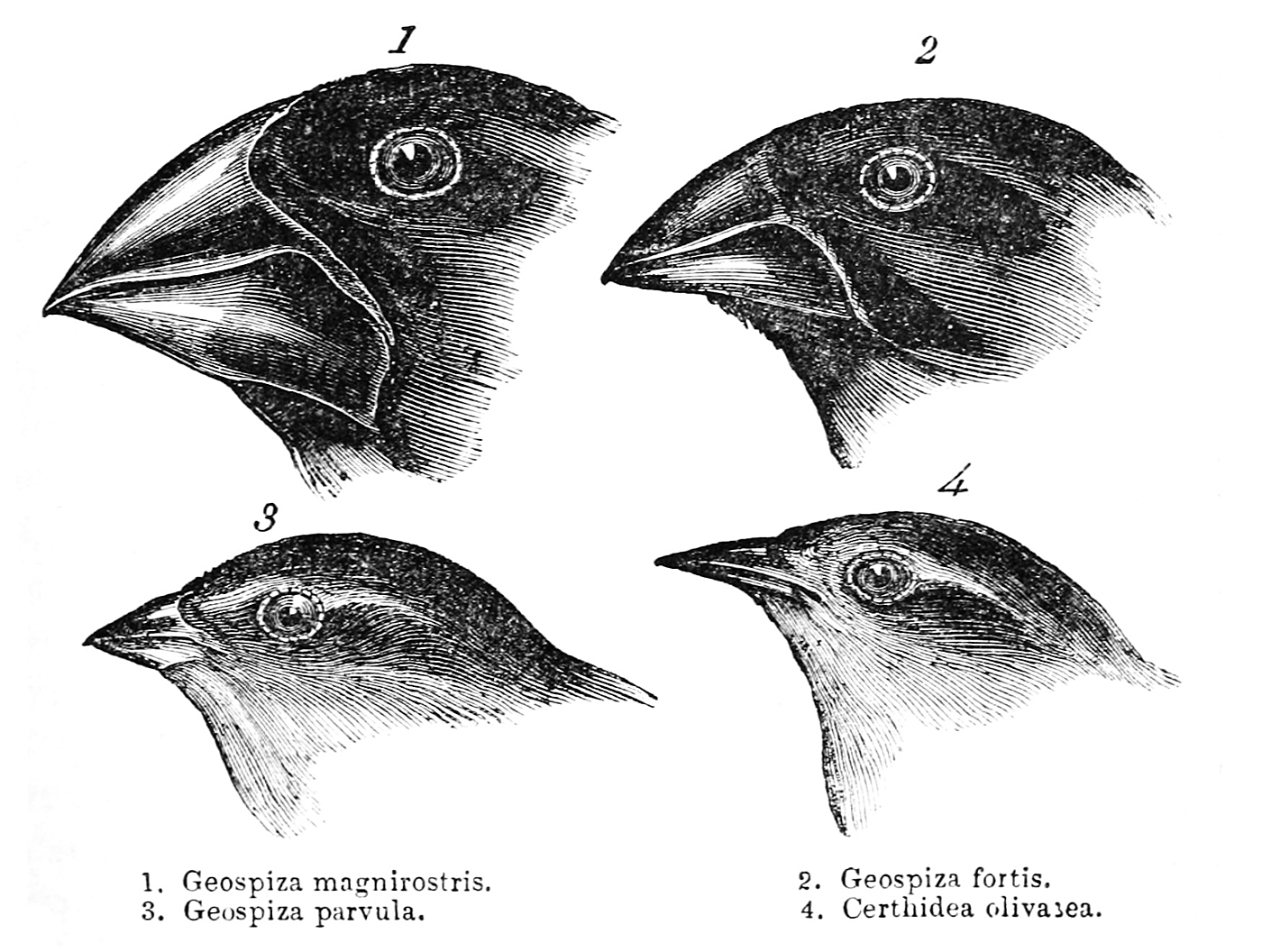

Anyway — Wikipedia explains that the competitive exclusion principle comes from biology. It means that two different species who compete for the same resource in the same habitat cannot coexist in stable equilibrium. One is going to dominate, and the other will be forced to find a new ecological niche or face extinction.

You probably recognize this from high school biology: imagine an island inhabited 50% by long-tongued anteaters and 50% by short-tongued anteaters, an animal I have just invented. With even a slightly longer tongue, you can eat a few more ants in a single bite, and reach a bit deeper into the anthills. So in the first generation, the long-tongued species is going to get slightly more food than the short-tongued species. This will translate into slightly higher rates of survival and reproduction, which means the second generation of anteaters on the island will be slightly tilted towards the long-tongued species — perhaps 51/49.

This miniscule advantage might not seem like a big deal. But play it forward long enough and the advantage accumulates — turning into quite a catastrophe for the poor short-tongued creatures, who are eventually wiped out:

This type of “winner-take-all” dynamic is familiar to those of us who work in the technology industry. The basic goal of venture capital is to identify long-tongued anteaters early, give them the resources to grow even longer tongues, and reap the benefits of the competitive exclusion principle. When it happens, it can work fantastically well for the shareholders of the dominant species.

But unless you were paying extremely close attention, you might have missed a puzzling paradox:

Venture capital “grand slams” are extremely rare, but the competitive exclusion principle is a mathematical axiom that applies to every market. It says that in every niche where two species are competing for the same scarce resource, the one with an advantage — no matter how slight — will drive the other out entirely.

So why aren’t there more markets with dominant winners like Uber, Facebook, and Google? And even in those markets, what explains the existence of Lyft, Snapchat, and DuckDuckGo?

To untangle this apparent contradiction, we need to move beyond theoretical habitats and into the real world.

In 1961, just a year after the paper that coined the term “competitive exclusion principle” was published, a British ecologist named G.E. Hutchinson published his own paper, “The Paradox of the Plankton,” which contained the germ of an idea that can help us resolve the dilemma.

Toward the surface of large bodies of water, there lives a species of plant called “phytoplankton” that are shaped like tiny Christmas ornaments:

Phytoplankton survive on a delicate balance of minerals from below and sunlight from above. This is a surprisingly competitive business. There are only so many circumstances where the conditions are right. The most critical factor required is an upwelling of water from the deep, because this water is most rich with nutrients like iron that the phytoplankton need to survive. When a good upwelling happens, massive blooms of phytoplankton can emerge within days.

These blooms can be visible from space. Here’s a patch of sea off New Zealand on October 11th, 2009:

And here’s that same spot, 14 days later:

(Fun fact: without phytoplankton we would be screwed. They produce more than half of the oxygen we breathe, and suck 10 gigatons of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere each year. So a huge shout-out to NASA for taking these images and studying phytoplankton!)

The weird thing G.E. Hutchinson noticed about phytoplankton back in 1961 is that, despite living perched on the edge of survival in a harshly competitive ecological environment, multiple species seem to coexist indefinitely. In other words, phytoplankton may not abide by the competitive exclusion principle.

The reason we know this is by experiment. Marine biologists go out on boats and take samples in various patches of water, and each time they see the same result: multiple species of phytoplankton. In theory, they should see a single dominant species, but this is almost never observed in practice. And it’s not just phytoplankton. In species and habitats all over the world, the competitive exclusion principle seems just isn’t observed as frequently as you’d expect.

Why?

There are two complicating factors, and they each have direct bearing on the ecology of businesses, too:

First, environments change. The dominant end state — equilibrium — may not ever be reached in practice, because by the time the fittest species in a niche approaches dominance, external changes may erase their edge. In the case of phytoplankton, maybe Species A is more efficient at eating phosphate, and Species B has a taste for nitrate. If the upswell from the ocean floor has varied mineral content over time, we’d expect variation in the relative success of Species A and Species B.

This happens in economies, too. There was once a time when IBM was a dominant force in computing, but the environment changed, and now they are a shell of their former self. (They’re still important, but nowhere near as important as they once were.)

So, change dismantles dominance. But not always. It’s a helpful mental model, but not terribly predictive. Luckily, in his 1961 paper on phytoplankton, G.E. Hutchinson came up with a theoretical framework to help us predict when the competitive exclusion principle will and won’t apply. It’s all about relative timing. If the time it takes for the environment to change is longer than the time it takes for an advantaged species to reproduce, then we should expect to see one species dominate. They’ll have the stability required to fully exploit their competitive edge. But, if the environment changes at about the same rate as it takes for species to reproduce, then we should expect to see constant fluctuation, because advantages come and go too quickly to allow for compounding returns. The most curious case is when the environment changes much faster than a species’ reproduction rate. In this circumstance, competitive exclusion is still possible, because in order to survive, each individual member of the species will need to be able to handle the varying conditions.

These principles can be applied to markets. For example, if you think you have a shot at dominance, it’s better to enter a market that has very little environmental change. (Coca-Cola comes to mind.) This is the reason why some investors, most notably Warren Buffet, have steered clear of technology. Change happens too fast to afford compounding advantage.

But the environmental change rate is just one reason we don’t see competitive dominance in the wild as often as the theory seems to predict. The other reason is that competitors are typically less competitive than they seem.

The closer you look, the more differentiation you typically discover among competitors that may superficially seem to employ the same strategy. For example, some species might feed at night while others feed during the day, enabling them to co-exist. Others might focus on a slightly different geography, or slightly different food source.

This happens in markets, too. It may seem like Uber and Lyft are functionally equivalent, but there’s a reason some people use one more than the other. One may be bigger, but they don’t achieve 100% dominance, the way the competitive exclusion principle would predict.

When you look at two species from a distant view, it’s easy to overlook a lot of this detail and abstract them into “complete competitors.” But as you zoom in, the additional detail you observe will monotonically push your conclusion toward less commoditization, and greater differentiation. This makes it less and less likely that a species — or a business — will be pushed out by some “dominant” competitor. Because the environment changes, and because competitors aren’t as complete as they seem, it’s actually somewhat rare to find truly dominant species that play the competitive exclusion principle out to its imagined conclusion.

It’s like Newton’s first law of motion: objects in motion tend to stay in motion. Advantaged species tend to dominate completely. True in the abstract, useful to know, but rarely seen in our lived experience. Reality is filled with friction.

So, what’s the upshot? How can we apply these ideas to help us make better strategic decisions? A couple thoughts:

- Stasis is good. The nice thing about “boring” industries is they’re stable, which gives you a longer runway to exploit your advantage. Durability is good, and it’s easier to be durable when things don’t change.

- Serve simple needs. The more complex and varied your customers’ desires, the harder it will be to resist fragmentation. It’s good to pick a market that’s large, and where everybody values the same things, even when you zoom in and observe those values in great detail.

- Compete to be unique. Don’t compete to be “the best” — there’s a nearly infinite variety of ideals you can strive towards. Niches are often larger than they may appear from a distance. Plenty of models can win.

Anyway, that’s all I got. I’m glad I looked it up!

What’d you think of this essay?

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!