A few weeks ago, rental car company Hertz filed for bankruptcy. While there isn’t anything surprising about that — after all, air travel has slowed down and a huge part of their business is tied to travel — there is one very surprising fact. About a week after they filed for bankruptcy, their stock price shot right back up.

At the beginning, the Hertz situation was fairly similar to most other bankruptcy processes. The demand for car rental plummeted because of a big economic shift (caused by Covid-19) and so their business tanked. To make matters worse, unemployment increased and the demand for used cars fell, which was one of their largest assets. On May 22, Hertz filed for bankruptcy when they had $19 billion of debt on their balance sheet and around 700,000 idle rental cars.

Most investors gave up at this point. Legendary investor Carl Icahn sold his 55.3 million shares of the company on May 26 for around $40 million. An SEC filing from March showed his total position at $1.88 billion so the sale resulted in over $1.8 billion in losses for Icahn. The stock was trading at $0.56 per share, down from $20.29 just a few months prior. And it made sense: if the company was going bankrupt, equity holders would get wiped out completely. Selling for $40 million is better than nothing.

From there, things started to get weird. Hertz' stock price rose from $0.56 on May 26 to $5.53 on June 8 because of the hysteria caused by Barstool Sports founder Dave Portnoy and a band of retail investors mimicking his trades on Robinhood.

Basically, Portnoy posted videos where he pumped up the stocks he was investing in. As the loud (and often brash) founder of sports media empire Barstool Sports Portnoy had built up a large audience of loyal followers. Once sports -- and sports betting -- stopped, many people switched from getting Portnoy’s take on a game to his take on a stock.

Typically, it’s impossible to raise equity capital during bankruptcy. Why would anyone want to hop in to the lowest priority security of a company that’s going to reorganize or liquidate? Even the debt holders likely won’t be paid in full, so equity holders don’t get anything. But the stock kept rising.

And while retail investors were propping up the share price (signalling high demand), Hertz did the thing any enterprising business would do: give customers what they want. They asked the courts if they could raise money by issuing equity, selling more shares to the retail investors that were keeping the price above zero.

And the judge agreed to it. On June 11, Hertz was approved to issue equity, which at the recent peak price would have been worth around $1 billion. The cash that they raise will go to the Hertz “estate”, which means it will go into a pool to pay the lenders.

And to top it off, several Hertz directors sold shares near the peak of this bubble — salvaging a lot more cash than they would’ve otherwise received.

You may have heard the story of Hertz already. But in this article I want to dive into the financial guts of bankruptcy, tease apart what typically happens, and explain why the Hertz situation is especially strange. Let’s dive in.

Why Would a Company Use Debt at All?

When thinking about the Hertz bankruptcy, the first question you might ask is, why did they have so much debt in the first place? Excellent question.

In order to understand bankruptcy you have to understand how companies raise money. There are two ways to finance a company: debt and equity. Every form of capital is one of these. And unlike most goods, when talking about the cost to purchase capital we talk in percentages rather than absolute values. A pair of sneakers might cost $150 where a senior secured loan might cost 4.5%.

Broadly, the difference between equity and debt is that debt is borrowing money while equity is selling ownership. Equity is typically raised when things are uncertain with a business. It participates in the upside (if the company does well, the owners of the company do well), but it also has nothing preventing it from going to zero.

Debt is raised when there is more certainty about the business. Lenders only receive compensation through the agreed upon interest rate — they do not participate in the upside. For an example think of your house. If the value of your house increases, the bank doesn’t get any more than what you originally agreed upon.

The downside of debt, however, is that it sits above the equity holders in the capital stack. This increases the risk of the business for shareholders. If you can’t make a mortgage payment, the bank takes your home. It’s a similar story with corporate debt.

So which should companies use to finance operations? For mature companies, debt is often the preferred financing method because it’s cheaper. It’s cheaper for two reasons: it’s less risky (so investors require a lower return), and it lowers taxes. To make this a little more concrete, let’s use some examples.

Lower Risk

Imagine you own a hardware business that has $50 million in revenue and $10 million in operating income in Year 1 (ignore taxes for now). Let’s imagine you need $20 million in financing to spend on a new high-tech manufacturing facility. The reason you want to buy this new facility is it lowers your costs a lot: if you can purchase it, you will make $15 million in operating income in Year 2 instead of $10 million.

But you don’t have $20 million in cash on your balance sheet. Instead, you might have the following financing options:

- Take out a $20 million bank loan with a 10% interest rate, or

- Sell 25% of the business for $20 million

Let’s look at what happens with each option.

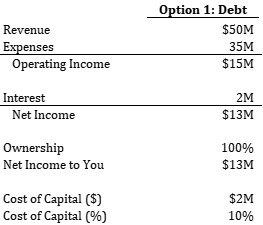

If you took option 1 (the debt), you would end up with $13 million in net income in Year 2. It works like this: with the new facility, your business makes $15 million in operating income. That’s great! But remember you borrowed money to buy the facility, and you still have to pay interest. With a $20 million bank loan at a 10% interest rate, that’s $2 million in interest. $15 in operating income minus $2 million in interest leaves $13 million in net income.

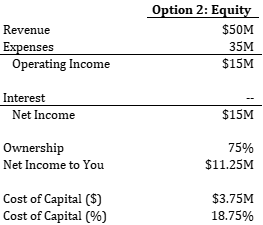

If you took option 2 (the equity), you would end up with only $11.25 million in net income in Year 2! Again, with the new manufacturing facility, your business makes $15 million in operating income. In this scenario, there is no debt, so there is no interest. So the company earns $15 million in net income. But, remember in this scenario you sold 25% of your company. So even though the company earns $15 million in net income, you personally only get $11.25 million of that.

So in this case, the debt cost the existing shareholders $2 million (10%) while the equity cost them $3.75 million (18.75%). So, the debt would be cheaper from a cost of capital perspective.

This advantage is exacerbated when earnings are growing! If your company instead grew from $10 million in net income to $20 million in net income, the debt would still cost 10% but the equity would now cost 25% because it would be worth $5 million.

Similarly, if your company only had $5 million in net income, the debt would still cost 10% but now the equity would only cost 6.25% ($5 million earnings times 25% = $1.25 million, which is 6.25% of the $20 million raised). But getting any kind of investor for a business that’s shrinking is a tough proposition.

Lower Taxes

The other advantage debt has is that it lowers the company’s taxes (which we ignored in the last section for simplicity). The main difference here is that interest expense actually reduces pre-tax income, where the cost of equity doesn’t appear on the income statement. This means that the more interest expense you have, the less taxes you pay.

So while there are a lot of variables involved, debt is almost always a cheaper source of capital. And most of the time lenders are happy to loan you money if you have a business with stable cash flows, a reasonable amount of other debt, and a strong asset base (examples include real estate, heavy machinery… or perhaps a fleet of automobiles).

How Bonds Work

Say you are a public company and you want to issue debt. One common method to accomplish this is to issue public debt, called bonds. The transaction is the same as any other debt instrument: a lender gives money to a borrower for a period of time. In exchange, the borrower pays an interest rate to the lender for the right to borrow and use their capital.

Bonds are usually issued at par value: $1,000. You can think of this like a stock price, but for debt. The total value of debt could be in the millions, but it’s easier to measure and trade using $1,000 blocks. Retail investors can purchase corporate bonds on most major brokerages.

At first, it might seem strange to be able to trade debt. For equity, it’s simple. If you think the company is worth more than its current value, you purchase the stock (and vice versa). However, the debt will never pay more cash than what’s stated on the contract. It doesn’t have any upside; only downside (if the company can’t make payments).

Because of this investment profile, lenders earn an interest rate on their money: the higher the interest rate, the higher the chance of failure.

So what changes the price of bonds? While a bit simplistic, basically two things: opportunity cost of capital, and risk of the company.

The opportunity cost of capital refers to all the other options that investors have. With equities, the future cash flows are quite uncertain. But with debt, they are laid out in contract. Investors can compare and contrast between debt classes or securities within classes and select which they think has the best risk-adjusted return profile.

As an example, consider the 10-year Treasury bill — with a rate of ~1.25% — against an 8% corporate bond. The Treasury bill is loaning money to the US government. For academic and practical purposes, it’s considered risk-free. If the US government can’t pay its debt, the rest of the system is really screwed. The corporate bond is lending money to a company. It’s fairly low-risk, but a higher chance failure. Investors are compensated with a higher return.

But what if the Fed raised the Treasury rate to 8%? Now a risk-free asset has the same cash flows as a risky asset. So, the price of the corporate bond would drop — who would pay the same amount when they could move their money into a safer investment? The opportunity cost of other investment options drives a lot of price movements in bonds.

The other big thing that affects bond prices is the risk of the specific company. If a company is performing poorly, the lower their cash flows. And the lower their cash flows, the higher probability that they can’t pay their debt. So if the operations of a company are deteriorating — due to economic activity, poor management or any other reason — bonds will start to trade lower because the probability of default increases.

Most of the time a small amount of debt is harmless, and even a large amount of debt often still results in positive outcomes for all stakeholders involved. It just adds leverage to the outcomes: higher highs and lower lows.

What Happens During Bankruptcy

Chapter 11 bankruptcy is what most corporations file for when they “go bankrupt.” There are several other kinds of bankruptcy; the common are Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 which are both forms of personal bankruptcy.

Often, Chapter 11 bankruptcy is initiated when a company can no longer make an interest or principal payment on their debt. Most of the time — and in the case of Hertz — the company voluntarily files for bankruptcy. They might do this to preserve cash or to have better negotiating leverage through the bankruptcy proceeding, and also to receive access to capital markets (which typically wouldn’t be interested in buying debt or equity in a stalling company with a lot of leverage).

Once a company declares bankruptcy, their debt payments get put on hold and major decisions outside of the course of regular business have to be approved by the courts. Oftentimes the company continues operations but issues a debtor-in-possession (DIP) loan. This loan moves to the top of the capital structure and gives the company some breathing room to operate as it navigates the bankruptcy process.

There are basically two outcomes as a result of a bankruptcy process: reorganization and liquidation. In a reorganization, the company continues to operate, just with a different capital structure. This is how companies like General Motors, Delta Airlines and Hostess declared bankruptcy but still operate today.

The other possible outcome is liquidation. In this case, the creditors and courts decide the company is worth more as the sum of its sold parts rather than as a going concern. So, the company goes through an asset sale to satisfy as many of their liabilities that they can.

One of the most important questions through bankruptcy is this: how much is the company really worth? For most large businesses, there are typically several tranches of debt. Each one has a different seniority. The most senior debt is the safest, followed by “subordinated” unsecured debt that’s not collateralized to any specific assets. Next in the preference stack is preferred equity, and then common equity is the riskiest. Common equity is what’s traded on the stock market.

Once a company enters into bankruptcy, each party is trying to figure out the true value of the asset (company) to understand which debt tranches go to zero and which will still get their money.

Almost always, the existing common equity goes to zero. It’s rare that a company that declares bankruptcy has a strong enough business to be worth more than its debt such that equity holders still have something left over.

If the business emerges from bankruptcy at all, the business will have equity (someone has to own it) but the equity will be granted to previous debt holders. That’s one reason why almost all of the money that’s made in distressed investing comes from selecting the right debt security at the right price — they could end up with equity, which has the potential for a higher return.

Why the Hertz Situation is Crazy

As mentioned before, once a company enters bankruptcy each security trades in accordance with how much it anticipates it will get back. Senior secured debt usually trades near par (because there’s only a tiny percent chance it will go to zero) while common equity trades near zero (because there’s only a tiny percent chance it will be anything but zero).

In fact, once a public company declares bankruptcy, the major stock exchanges usually delist the stock because it doesn’t have sufficient trading volume; no one is interested in buying it.

The Hertz situation is crazy because they are selling something that’s worthless. It’s as close to certain as you can get that their common equity will go to zero. Yet, the hype has led to a lot of demand from retail investors. So much so that it would be foolish for Hertz to not raise money from them. If people want to give away their money, isn’t it the responsibility of managers to accept it?

While many people have moral arguments against this, I take a bit more of a hands-off approach. “Greedy corporations take advantage of retail investors” I don’t support. But, “opportunistic corporations raise capital due to of high demand from reckless gamblers” is a much different story. The filings for the equity issuance clearly outline the risks of the “investment”, and to me that might be enough.

When the dust settles, average people may end up sending to big bank lenders and hedge funds that invested in the debt. I don’t love that idea. However, if you’re an adult you have the right to bet your money on a poker hand or soccer match, and under that framing, I’m not so sure we should try to stop it.

Editor’s note: a few minor updates were made on June 21, 2020 to improve the accuracy of the piece and further clarify some features of the bankruptcy process (although the overall narrative remains the same). Thanks to Petition — a fantastic bankruptcy and distressed debt newsletter — for bringing the issues to my attention and also for writing one of the earliest articles summarizing the situation.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!