Sponsored By: Uptrends.ai

This essay is brought to you by Uptrends.ai, it's like Google Trends and Wall Street merged into one powerful tool. Get your first-month subscription 100% free by entering the code EVERY when you sign-up and jumpstart your financial journey.

Currently, our platform is exclusive to desktop users. So, pull up your chair, log in from your desktop and start leveraging the power of Uptrends.ai to stay a step ahead in the market.

One of the most delightful things about being American is the middle finger. There is, of course, the physical satisfaction of righteously flipping the bird. Cut off in traffic? Extend it. Grumpy at an opposing sports team? I would recommend the double hand thrust. However, as I learned in my recent trip to Europe, bad drivers are everywhere, and the physical act of shoving your finger into the sky feels just as good in England as it does in New England.

What I’m talking about is the American tendency to flip the bird ideologically. It is rugged individualism, the ridiculously relentless optimism that makes America unique. Perhaps the defining American mindset is looking at terrible odds and thinking, “Meh, I’ll do it anyway.”

My favorite example of this is building a venture-backed startup. This is a market with a 98% failure rate. 98%! Any sane, rational person would avoid something that fails this often. Despite producing so many flops, America is the technology startup capital of the world. All of the good of silicon chips and computers and genetic technology is only possible because Americans reject the odds. This attitude does make the country chaotic, but it also makes it great.

However, I feel a tremor in tech—an intellectual wobble, if you will. With the threat of recession and rising interest rates, there's been a cooling of startup ardor. Few people want to admit that they're afraid to pursue the startup dreams they once held. Instead, they point to economically "rational" explanations for their reluctance. A popular framework I often hear cited is the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH).

For the unfamiliar, EMH is an idea from the 1960s from economist Eugene Fama that states that a public stock price perfectly reflects all available information, and therefore consistent alpha generation is impossible.

I vehemently disagree with this framework. It is dicey in the public markets and borderline dangerous in the context of private markets. You are best served by investing in the opportunities where you have a true competitive edge. These are everywhere. In public markets and in private, alpha abounds.

When founders and investors buy into EMH, they stop taking shoot-for-the-moon bets because they believe they're too risky or irrational, and the markets always behave rationally. They are selling tomorrow’s better future for the chance of statistically average returns today. If progress is made one middle finger at a time, EMH proponents are sitting on their hands, behaving themselves in Sunday School.

While theoretically the EMH is possible, it does not reflect reality. Markets exist on a spectrum of efficiency, not in absolutes. Understanding when and how to identify inefficiencies in markets is perhaps the most important skill a person can gain.

Today I would like to argue my case against EMH in two parts:

- Public markets aren’t efficient.

- Private markets are even less efficient.

Let’s dive in.

Picture this - Google Trends and Wall Street merged into one powerful tool. Welcome to Uptrends.ai - your personal stock market news analyst. A first-of-its-kind platform designed to simplify investing for everyone, where chatter turns into valuable trading insights, highlighting trends and events that count.

With Uptrends.ai, trading the news has never been simpler. Better yet, get your first-month subscription 100% free by entering the code EVERY at checkout.

Like a Bloomberg Terminal, our platform is only for desktop users. So, pull up your chair, log in from your desktop, and start leveraging the power of Uptrends.ai to stay a step ahead in the market.

Why public markets don’t work

To better understand why EMH is so dangerous, it is helpful to examine the definition. EMH states that it is impossible to consistently outperform the market by using publicly available information. This is because asset prices already reflect all available information that would affect their price.

EMH is based on the idea that all investors are rational and will act in their own best interests. They will buy assets when they believe they are undervalued and sell them when they believe they are overvalued. As a result, prices will quickly adjust to reflect new information, making it impossible to consistently beat the market.

I know, I know, that sounds authoritative. It’s a nice, clean, simple view of reality, and it’s comforting to people who believe it. But there are so many issues here!

First, and most importantly, EMH argues that over time stocks are always priced appropriately. This is obviously untrue—just look at underpriced stocks in certain sectors (e.g., tech 10 years ago). EMH doesn’t offer some magic formula for determining how long it will take a stock to be “priced appropriately.” I’m sure Walmart’s stock will be negatively affected by the heat death of the universe, but in the meantime, that doesn’t help me post 10% yearly returns.

The second error is the assumption that information is priced in. Again, this is, like, totally wrong. There’s debate, even among EMH proponents, about what type and quality of information a public stock price reflects:

- The weak form of the EMH states that stock prices reflect all past information.

- The semi-strong form states that stock prices reflect all publicly available information, e.g., SEC filings.

- The strong form states that stock prices reflect all information, both public and private.

My sense is that most people who adhere to the Efficient Market Hypothesis believe version three is the default of this rule. Again, this obviously isn’t true. Investors have information asymmetries constantly! For example, members of the U.S. Congress have consistently beaten the market, most likely by using their knowledge of upcoming regulation. It just depends on how you timebound that asymmetry.

EMH is an economic framework, not a scientific law. Time advantages and information asymmetries absolutely exist. Knowing it is a framework and not an absolute means that you can be justified in your decision to ignore it.

The biggest counterfactual to EMH comes from a 1984 lecture by Warren Buffett. He argued that the way to consistently beat the market was (of course) his way. For much of his early investing career, he invested in businesses where he felt that the value assigned by the stock market did not accurately value the business represented by the stock. Over a long enough time period, the superior cash flows of that business would be recognized by the market, giving a high return.

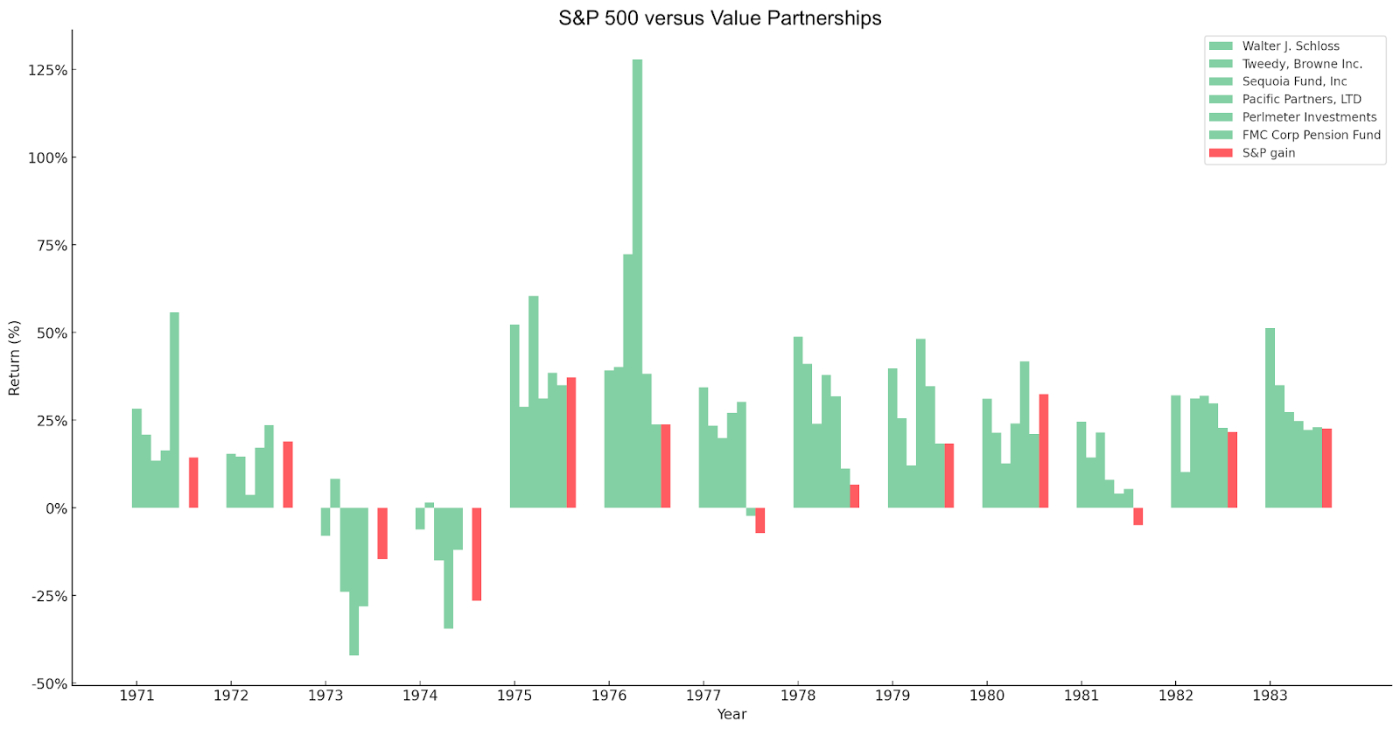

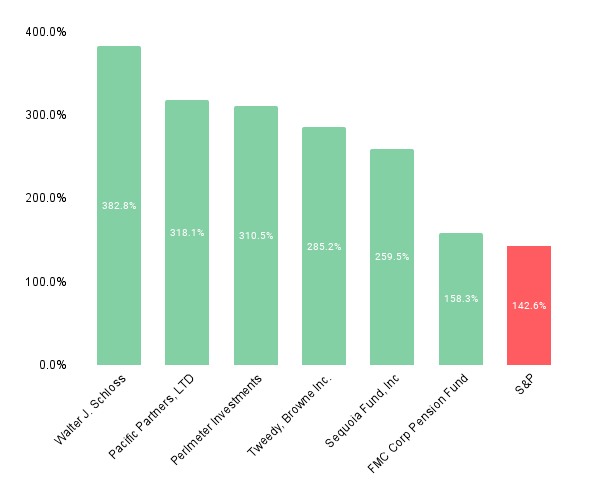

This school of thought, called value investing, was practiced by a variety of managers. Buffett audited their returns and compiled their results, which were pretty staggering. They act as strong evidence against the legitimacy of EMH. Here are their returns on a yearly basis from 1971 to 1983:

And here is the cumulative returns over the same period:

Note: You can really quibble with these numbers depending on how you include dividends and buybacks, but you get the idea.

Values investing’s success contradicts EMH. If EMH were correct, these kinds of decade-long results should be impossible. But you can see the chart—they are possible. Buffett finished his lecture with this deliciously juicy mic drop:

“There seems to be some perverse human characteristic that likes to make easy things difficult. The academic world [that proposed EMH] has actually backed away from the teaching of value investing over the last 30 years. It’s likely to continue that way. Ships will sail around the world but the Flat Earth Society will flourish. There will continue to be wide discrepancies between price and value in the marketplace, and those who read their Graham & Dodd will continue to prosper.”

Note: I’ll publish a deep dive on value investing in a week or so. Please subscribe if you would like that in your inbox.

The other major counterfactual to EMF is the existence of public market bubbles. From my recent piece on the AI bubble we are currently in:

“Bubbles are when people buy too much dumb stuff because they think there is someone dumber than them they can sell said stuff to. Take the crypto bubble in 2017. When Bitcoin mooned, a variety of companies pivoted to the blockchain and saw huge gains in their stock price. Those companies included a furniture firm, juice makers, a gold miner, and my personal favorite—a sports bra manufacturer. The most telling example was Long Island Iced Tea, which had a market capitalization of $23.8M. It announced that it was changing its name to 'Long Blockchain Corp' and saw its stock boom by 183% in one day. In pre-market reading it had risen by over 500%.”

This type of mass irrationality also contradicts the EMH. If markets were efficient, multi-year bubbles wouldn’t happen—after all, the crypto bubble lasted roughly three years. And to be fair, bubbles pop and assets are eventually priced appropriately. But there is still alpha available, as hedge fund George Soros said, “When I see a bubble forming, I rush in to buy, adding fuel to the fire.”

This is a deeply empowering idea. Investors can see incredible outcomes if they have a rational understanding of the odds and then determine they can beat them anyway. Bubbles show that public equities are the most scrutinized, evaluated, and generally available assets in the world—and they still aren’t efficient. There is an incredible amount of alpha available. You can beat the market, but only if you are hyper-aware of how and why you are beating it. Since 99.999% of people don’t have a genuine edge, you probably shouldn’t day-trade. However, there is immense comfort in knowing that you can still beat the odds in the right circumstances.

In summary, if EMH were wholly true there would not be categories of managers that consistently beat the market, or extended periods of irrationality. And if EMH isn’t true in the public markets, you can imagine how dangerous it is to believe that the theory applies to private markets.

Why private markets are even less efficient

Let’s go back to the example of startups. Here, all of the things that make public stocks more efficient disappear. Startup equity sales happen rarely, deals have essentially no public information, and pricing is set by a limited number of participants. As a result, the market is more inefficient, which, counterintuitively, can make it more profitable for investors. Secrecy and information disparity creates big opportunities for the investors who are in the know.

This feels a little weird to argue—the American ideal of individualism is the left jab to the right hook of equality. But it doesn't change the facts of our current system, in which inefficiency is a good thing for the individual freed from EMH brain. The more people there are investing, and the more information they have, the worse the returns will be per person.

Morally, as an individual citizen, I think we should allow more access to these deals. It sucks that the average Joe in RandomTown, USA couldn’t get in on the cash grab that was Uber in 2014. There’s a reason that people tasked with capital deployment would like to retain their barrier to entry.

This difference in access means that private markets are also subject to entirely different competitive dynamics. There aren’t that many public stocks to worry about—the U.S. stock exchanges have roughly ~6,000 stocks that represent 50%+ of the public equity value in the world—but you can trade for or against them in essentially infinite ways.

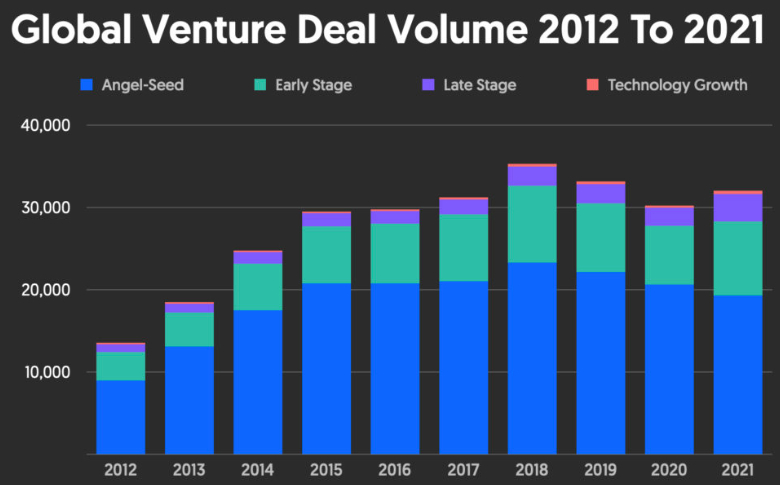

In contrast, there are more than 10,000 startups that raise angel rounds every year. Total deal volume is even higher.

Private markets will have more total inventory with less trading optionality built in. You either buy or you don’t. There isn’t any shorting, hedging, or price fixing. You’re either in or you’re out.

There have been multiple attempts to establish a market for growth stage startup equity, none of which have taken off because the lack of liquidity is a feature, not a bug! The wise investor wants the exact minimum number of investors required to invest in these deals and not one more.

I was inspired to write this article after VC friends told me “AI was priced in” for a company raising a round. This was dumb on multiple levels. One, we have no idea where profit pools will occur in this new tech paradigm. Two, the twin sins of EMH—time averaging and information scarcity—were happening right in front of us. For this startup, I happened to know that its AI product had crazy high churn, but the founders weren’t making that obvious to potential investors. This is an information advantage I have that won’t be priced in because I can’t bet against this startup. The closest proxy would be me investing in a direct competitor that has better numbers, but it’s not the same as shorting a public equity stock.

But that is just in tech startups, a small sliver of the overall market. There are 33M small and medium businesses in the U.S. alone. Each of these is private, and suffers from issues of time and information access, both of which mean there is significant investment opportunity. I’ve seen folks make millions from investing in everything from sneakers to home furniture to burrito stands. The point isn’t that private markets are inherently better; in fact, in many ways they are worse relative to public ones. What matters is that information and time arbitrage are way more powerful in private markets.

There are essentially infinite ways to make money. But the only consistent way to do so is to identify an investment opportunity where you have either a time or information advantage. I know some day traders who made $10M and quit. Others have gone higher and then lost it all because they didn’t know when their advantage had disappeared (or whether they were just lucky).

Freeing yourself from EMH allows you to recognize that opportunity is everywhere, nothing is priced in, and if you are patient, you can find a way to generate alpha.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Thank you for this article! This is maybe a dumb question: What's the definition of "stocks are priced appropriately". Appropriately versus what? Who's the judge? How do we know? When do we know? The example about tech stocks 10y ago ... if tech stocks collapse in next 10y, will we then say they were priced appropriately? Is this a moving target?