A couple weeks ago, Wish.com filed their Form S-1 with the SEC (under their corporate name ContextLogic). Wish has raised over $1.6 billion and was last valued at $11.2 billion in August 2019. The IPO should be a jolly moment, right? Maybe not.

The future doesn’t look great. Wish has rising customer acquisition costs. Their gross profitability is falling because a government subsidy on shipping is disappearing. It’s also not totally clear that a lot of people actually like their product.

It’s like Wish is running a government-subsidized non-profit dedicated to the noble cause of learning the most effective growth hacks on Facebook Ads. Instead of trading their stock, I might suggest reaching out to members of their marketing team and paying them lots of money to come work for you.

This isn’t actual investment (or hiring) advice, do your own research please don’t sue me thanks.

Alright, enough with the jokes and onto the analysis.

What is Wish?

Wish was founded in 2010 as a mobile-first discount commerce app. It works like this: first, a customer downloads the app (90%+ of user activity and purchases happen on mobile). Then, they scroll through photos of items. Wish sells everything from Bluetooth headphones to baking sheets to swimsuits. Most of the prices are 80 to 90 percent off of their original price, so it seems like you're getting a steep discount.

The key to their model is that customers trade price for convenience. When you place an order on Wish, it takes two to four weeks to arrive. On the backend, Wish places the order with manufacturers in Asia for a steep discount and sends it to you. While many discount retailers have to hold inventory in the U.S. (near their customers), without that cost, Wish can offer the lowest prices.

In slight contrast to Amazon, which competes on both price and convenience, Wish focuses exclusively on price. It turns out that there are many shoppers that value price over everything else, described by CEO Peter Szulczewski in a blog post from 2016 as “The Invisible Half”.

Especially early on, they leveraged Facebook and Instagram ads for growth. They became notorious for their… strange advertisements.

Most people who discovered the app in its early years did so through Facebook and Instagram, where it still regularly ranks among the platforms’ top advertisers. There, amid endless hyper-targeted campaigns, its ads have become notorious for their occasional weirdness, thanks to an algorithm that pulls in some of the most confounding products from Wish’s catalog of 200 million items: adult diapers with an attached rubber hose (?), shapewear ... for your face (??), and a $2 pile of what appears to be worms (???). There are no product labels on most of these ads, so you have to click over to Wish.com — or download the app on mobile — to find out what you’re looking at. (Source).

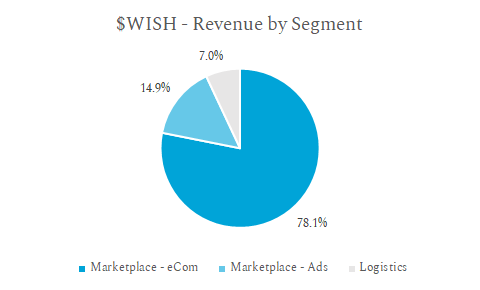

Wish earns most of their revenue from “marketplace services”, which includes their core eCommerce product as well as a native advertising product called ProductBoost. Marketplace services represent 93% of their revenue in 2019, of which 84% of that (78.1% of total) was their core marketplace revenue. The remaining 7% of revenue was from logistics services (delivering goods from merchants to customers).

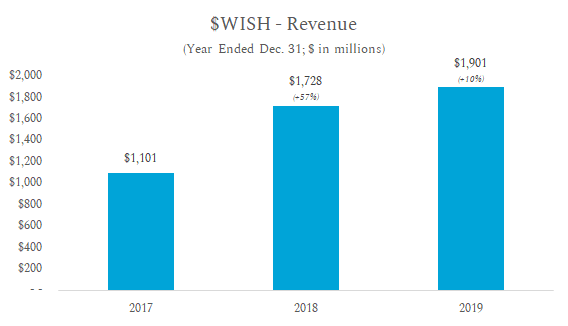

They ended fiscal year 2019 with $1.9 billion in revenue, up from $1.7 billion in 2018 (10% YoY growth) and $1.1 billion in 2017 (57% YoY growth).

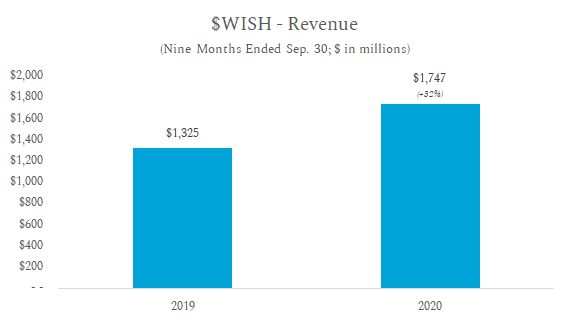

The nine months ended September 30 they had revenue of $1.7 billion, up 32% from $1.3 billion in the same period last year.

Shipping Rates & The Universal Postal Union

It’s not uncommon for value retailers to have a high-volume, low-margin model. Amazon has maintained a negative (or small positive) margin on its retail business for years and CostCo famously only makes margin on its memberships. This is no different with Wish, but with a big caveat: the model’s efficacy is predicated on a discount shipping policy by the Universal Postal Union Treaty. But the future of this law is murky.

For those unfamiliar with the Universal Postal Union (cough not me cough cough), they are a “specialized agency of the United Nations that aims to organize and improve postal service throughout the world and to ensure international collaboration in this area” (source). They were founded in 1874 to facilitate international trade. While some of the principles created by the UPU are obvious (uniformity of units of weight, for example), it also created discounted shipping rates for parcels to and from developing countries.

The goal was to help developing nations participate in trade to participate in the global economy and increase their quality of life. As part of the program, richer countries like the U.S. agreed to subsidize exports moving from companies in poorer countries to companies or consumers in richer countries.

These subsidies applied to parcels moving from China to the U.S. and many companies took advantage of this.

However, now that China is a much larger country, the Trump Administration decided that they didn’t want them to have discounted rates. So in October 2018, President Trump announced that the U.S. would exit the UPU in a year if the “group’s 192 members did not agree to reform the rates that countries charge each other when delivering mail and small packages across borders” (source). One industry executive even described the situation as “Trump having his own Brexit.” Luckily a new deal was signed in September 2019 with the stipulation that the U.S. would get to set its own postal rates starting in July 2020.

Just as planned, on July 1, 2020 the international shipping rate changed. Originally designed for mail, the UPU only regulates packages under 4.4 pounds. In the past, the cost to ship a 4.4-pound package from China to the U.S. topped out at $5.41 — less than it would cost a U.S. seller to ship the same item to a U.S. address. Now, under the current rate of $2.87 per package + $3.95 per kilogram (~2.2 lbs), that same 4.4-pound package will cost $10.77 — almost double.

And thus, we return to Wish. If shipping rates on cheap goods from China are rising, and a lot of the items on Wish are cheap goods from China… well, you can see the issue. From page 27:

Historically, our merchants in China have benefitted from lower shipping costs due to the Universal Postal Union Treaty (“UPU”). Certain expected changes to UPU postal rates that went into effect in July 2020 are likely to increase the shipping rates our merchants incur to ship products from China. The actions we have taken in our logistics program to mitigate these increased costs may not be successful over the long term. [Emphasis mine]

Regardless of if this exact policy remains intact, or if you believe in the policy, there’s no way out of this risk for Wish. They are trying to source from other countries (including the U.S. through their Wish Local program) but most goods still are prohibitively expensive to manufacture here because of higher labor costs. Their model is built on offering the cheapest goods. One could also say it was built on an international trade subsidy that’s disappearing.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

You should do another post on this

Now that the price has fallen to less than $2.5, would you invest in WISH ? I think it would help to read your perspective on this again - how did the company has done so far (not stock price) and what do you the future hold for WISH. I think reader will enjoy