.png)

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

The bug report was deceptively simple: A user noticed that their email signature formatting was off in Cora, our AI-powered email assistant. I asked Claude Code to investigate and fix it. By morning, the fix had touched 27 files, and more than 1,000 lines of code had changed. I didn’t write any of them.

A year ago, I would have spent my afternoon reading that code. Line by line, file by file, squinting at the migration that moved email_signature from one database table to another, Ctrl+F-ing for every instance of our feature flags.

This time, I spent 15 minutes making decisions, and the code shipped without a single bug.

Before AI, code review meant reading every line a teammate wrote. You checked for typos, logic errors, and style inconsistencies, the way an editor reviews a manuscript. Now my code reviews no longer involve reading code. And I’ve gotten better at catching problems because of it.

This is code review done the compound engineering way: Agents review in parallel, findings become decisions, and every correction teaches the system what to catch next time. The signature fix that touched 27 files? Thirteen specialized AI reviewers examined it simultaneously while I made dinner.

I’ll show you how I set it up, how it caught a critical bug I would have missed, and how you can start—even without custom tooling.

The death of manual code review

Reading code, even briefly, gave me a sense of the shape of things. I could feel when the codebase was getting too complicated. By letting go of manual review, I worried that I’d lose that clarity, and the architecture would wander off without me.

But I realized, too, that manual code reviews were no longer sustainable. When a developer writes 200 lines, their manager might spend 20 to 40 minutes reading it. The ratio of time spent writing code to reviewing it holds at 5:1 or 10:1—I can sit down with a cup of coffee, and the coffee will still be warm by the time I finish. AI has broken that ratio. The time it takes to generate code has collapsed, but the time it takes for a human to review code hasn’t. Something had to give.

The shift from manual review happened slowly. When Claude Code enacted a set of fixes, I’d ask it questions, then read the diff (the line-by-line comparison showing what had changed). When I was satisfied, I’d hold my breath and merge the changes into the main codebase.

Nothing broke. The code was fine. It turned out that asking Claude to explain its reasoning—what it changed, why, and what might break—caught more than my tired eyes scrolling through diffs.

After a while, that close read turned into a quick skim. The skim turned into a glance. Eventually I found that by the time I had asked my questions, I’d already hit “merge.”

I still understood how good the code was—that clarity just came in a different way. Instead of feeling the shape of the code by reading it, I felt it by interrogating Claude Code:

- “Walk me through what you changed and why.”

- “What assumptions did you make?”

- “What would break this?”

-

“Why did you ignore the feedback from

kieran-reviewer?”

That last one needs explaining. kieran-reviewer is an AI agent I built—a specialized reviewer trained on my code preferences. It knows, for instance, that I prefer simple queries over complex queries and clear code over clever code. It’s one of 13 reviewers that examine every pull request before I see it.

Why so many agents? No single reviewer, human or AI, catches everything in a 27-file change. A security expert spots authentication gaps but misses database issues. A performance specialist catches slow queries but ignores style drift. I needed specialists working in parallel, each focused on what they’re good at. Together, they catch what I might miss from a manual review.

Write at the speed of thought

That gap between your brain and your fingers kills momentum. Monologue lets you speak naturally and get perfect text 3x faster, and your tone, vocabulary, and style is kept intact. It auto-learns proper nouns, handles multilingual code-switching mid-sentence, and edits for accuracy. Free 1,000 words to start.

Using the compound engineering plugin

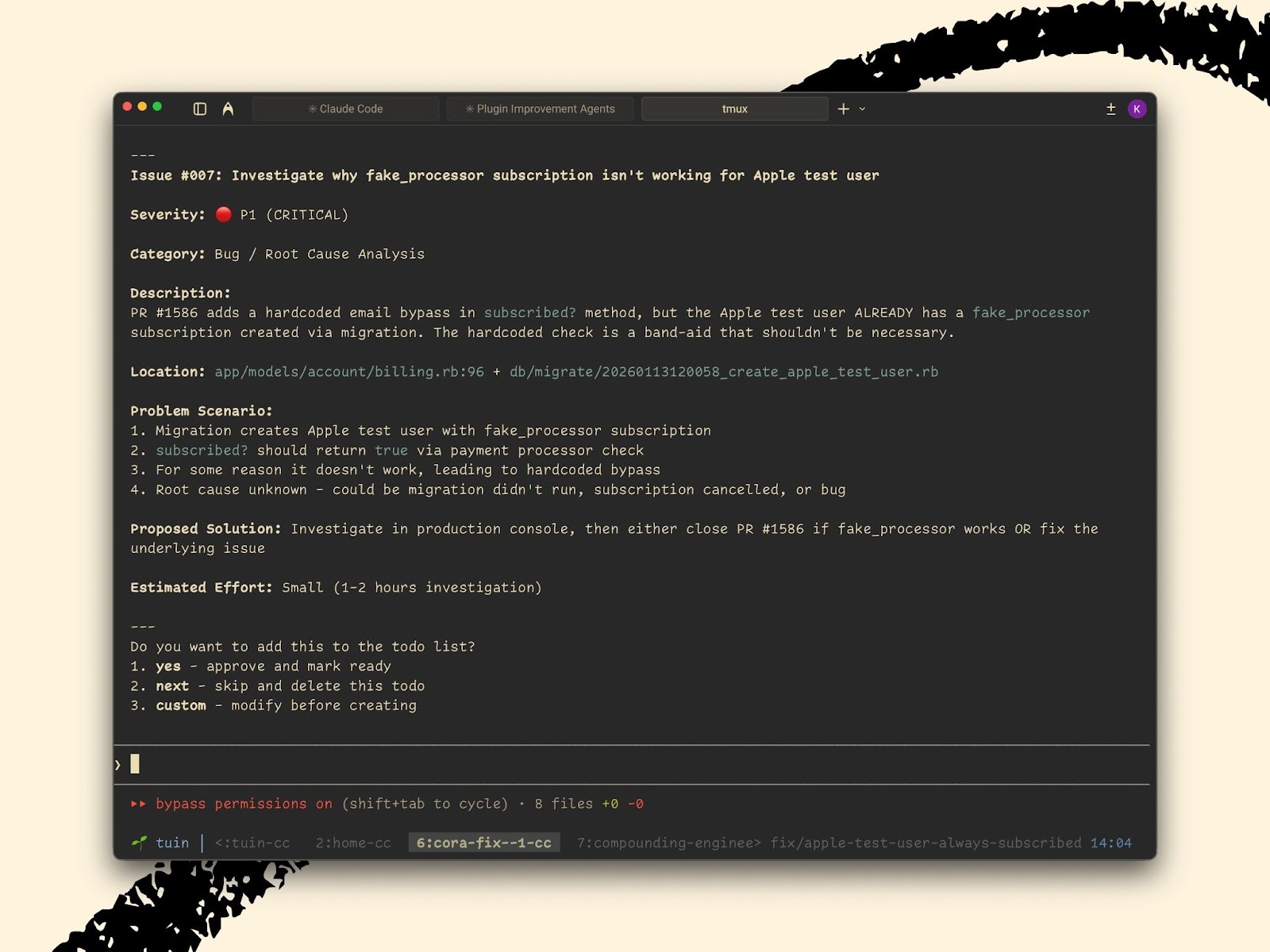

My system for code review is rolled up into the compound engineering plugin. It’s a set of files in your codebase that extend what Claude Code can do. Here’s how it works.

Slash commands are shortcuts you type in the terminal—like /workflows:review or /workflows:plan—that trigger workflows. Each workflow is a markdown file with instructions for what Claude should do when you invoke it.

Agents are specialized AI workers, each defined in its own markdown file with a persona and focus area.

For the email signature fix, I ran a single command: /workflows:review, which spun up every agent on its list at once:

-

kieran-rails-reviewerchecks my personal style preferences -

code-simplicity-reviewerhunts for over-engineering -

data-integrity-guardianvalidates database changes during migrations (when the structure of your database changes) -

security-sentinelchecks for authentication bypasses - Plus nine more, each with a specific focus

Ten minutes later, they returned with findings ranked by priority.

From findings to decisions

The agents produce findings. But a list of issues isn’t useful—I need to know what to do about them. So I run the next command: /triage

Triage takes all 13 reviewers’ findings, ranks them by severity, and walks me through each one. It presents every finding in the same way: Here’s the problem, here’s why it matters, now what do you want to do?

I can accept the recommendation (and the system creates a task to fix it), skip it (it’s not worth addressing), or provide specific instructions.

The signature fix surfaced three findings. The first was critical: The code had moved where we store a user setting, but one file still looked for it in the old location. If I’d shipped this, every user who tried to generate a draft response would have hit an error. The fix itself is trivial—point the code at the new location—but I never would have caught it scrolling through diffs.

The second was cleanup. A chunk of unused code, left over from an earlier approach. It wasn’t broken, but it was confusing. On the chance that someone did read the code in the future, they would wonder what it was for. I approved this change too.

The third was a nitpick—a minor redundancy, technically true but harmless. I skipped it. I’ll clean it up next time I’m in that file.

I got three findings and made three decisions in less than two minutes.

The critical finding alone justified the review. I never would have caught a mismatched reference on line 31 while scrolling through 1,000 lines at 6 p.m. The agents caught it in seconds.

The fix is never the last fix

The signature fix should have been simple. I’d make one change and be done. But sometimes when you fix a piece of code, you end up breaking another. This is just as true with human developers as with coding agents.

In our case, the first version fixed the signature formatting in Gmail, but it broke the plain text version of emails. Some email apps don’t display styled text, and now those users saw raw formatting codes instead of readable text.

So we fixed that. But the fix for plain text created extra blank lines for users who didn’t have signatures at all.

So I fixed that too. Then we discovered that when you reply to a heavily-styled marketing email, our formatting rules were leaking into the quoted text. Users saw gibberish like #outlook a { padding: 0; } in their message body.

I fixed that. Next we found that Cora was now appending your email signature after each suggested draft of an email, instead of just once at the very end. If you generated three options, you’d get three signatures. Which called for another fix.

Ten versions of the code. Four bugs we introduced while fixing the original. Hence the 27 files and thousand lines of code. Again, this is a normal part of any development process, human or AI. The difference is that here, we can codify our learnings to make sure we don’t make the same mistake next time.

The 50/50 rule

I spent 15 minutes fixing those bugs. Then I spent another 15 minutes making sure I’d never see them again.

After the signature mess, we created a document called refactor-email-content-rendering.md. It lives in our codebase, and it captures everything we learned:

- A chart showing every combination of user settings and what should happen in each case, so there would be no more guessing.

- A simple rule about which part of the system handles formatting: “The background process sends styled text. The Gmail connector never converts formats.”

- The exact format Gmail expects for signatures, pulled from actual emails we tested—not what we assumed, but what we verified.

That document is now part of the project. The next time anyone touches email rendering—whether that’s me, a teammate, or Claude—the AI reads it first.

In my first weeks using this workflow, Claude presented me with approaches that weren’t necessarily wrong, but didn’t reflect my preferences. What I consider “over-engineered,” another engineer might call “robust.” What I see as a missed pattern, someone else might not use at all. Three months and 50-plus reviews in, Claude’s plans largely reflect how I’d approach problems myself.

Better AI models make everyone’s output better. But your system gets better because you’re accumulating your own team’s knowledge. Your agents learn your preferences, and your review process reveals your blind spots. That’s where compounding happens.

So follow the 50/50 rule: Spend half your time reviewing output, half ensuring the lesson sticks.

Rethink reviews

Most engineers assume they need to read everything. That assumption made sense when humans wrote all the code. But it doesn’t anymore.

I shipped the email signature fix without reading most of the code. I reviewed findings and made decisions. I looked at screenshots in Gmail. But did I read the implementation details of how we extract email content? No. Did I trace through how the database change handles edge cases? No.

Yet the feature works. Users get properly formatted signatures. The tests—checks I write alongside every feature to verify the code behaves correctly—all pass. The screenshots look right. It took some time to let go of manual code reviews, but the results speak for themselves.

The trade I’ve made is that I won’t read every line, but a part of the time I would spend reading code now goes toward making the system smarter. I’m adding test cases for marketing emails stuffed with weird formatting. I’m capturing “when you change where data lives, check every file that reads it” as a rule the agents enforce automatically. This way, the next person who touches this code—human or AI—doesn’t repeat my mistakes.

If you don’t have the compound engineering plugin yet, start with three questions. Before you approve any AI-generated output—code, documents, or strategy decks—ask the AI:

- What was the hardest decision you made here?

- What alternatives did you reject, and why?

- What are you least confident about?

That conversation, which takes two minutes, surfaces what a 30-minute unfocused manual check would have missed. The AI knows where the tricky parts are. It just doesn’t volunteer them unless you ask.

Then apply the 50/50 rule. Spend half of your time fixing the immediate problem and half documenting it, making sure the problem never comes back.

The 27 files involved in rendering an email signature are waiting for the next feature. I’m still not going to read them all. But when I’m done, the system will know more than it did when I started.

Kieran Klaassen is the general manager of Cora, Every’s email product. Follow him on X at @kieranklaassen or on LinkedIn.

To read more essays like this, subscribe to Every, and follow us on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

We build AI tools for readers like you. Write brilliantly with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Deliver yourself from email with Cora. Dictate effortlessly with Monologue.

We also do AI training, adoption, and innovation for companies. Work with us to bring AI into your organization.

Get paid for sharing Every with your friends. Join our referral program.

For sponsorship opportunities, reach out to sponsorships@every.to.

Help us scale the only subscription you need to stay at the edge of AI. Explore open roles at Every.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.12.16_PM.png)

.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I started adding "splunk" like logging to find issues after the fact. I do have a growing list of unit tests. I agree, the amount of code that claude code can generate is too much. I was feeling like the development bottleneck. I'll probably keep both methods but I do like your idea of leveraging AI to find issues before PR merges. Very clever. Thanks for sharing.