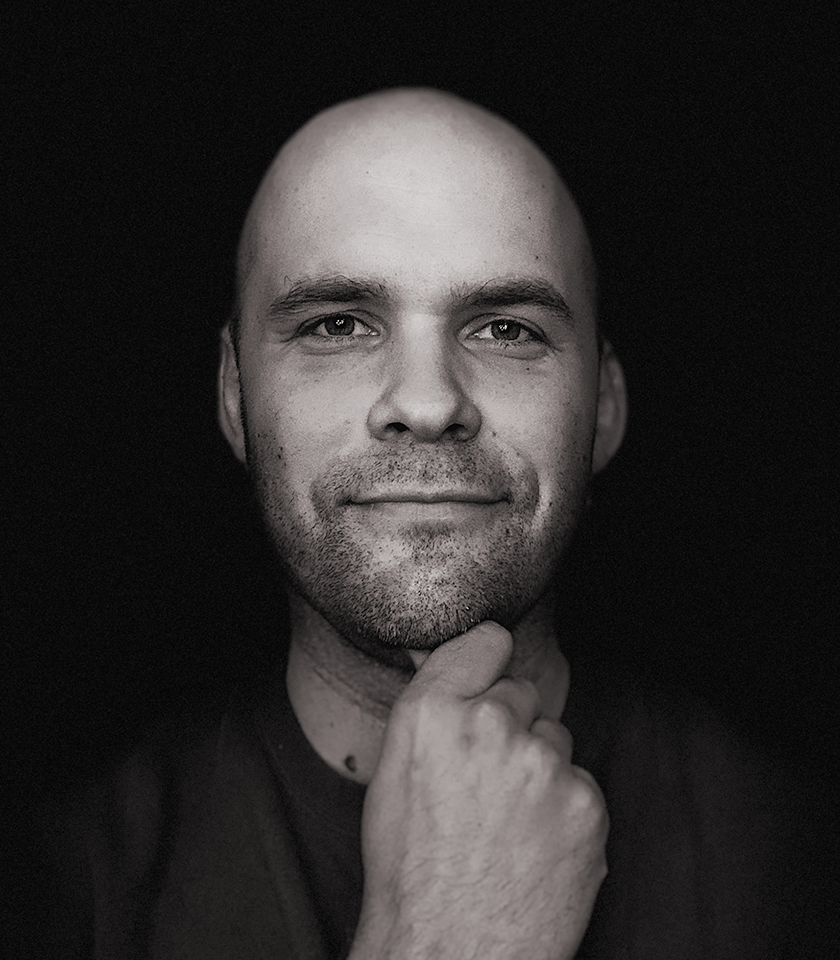

I’m sitting on a Zoom with the best-selling fiction writer Robin Sloan, author of Mr. Penumbra’s 24 Hour Bookstore and Sourdough.

He opens his notes app, nvALT, and the word “empire” is still loaded into the search box from a previous session.

“I’ve been going back to my notes a lot recently, looking for things related to fantasy stories, and epics,” he explains. He flips to the first note and it’s a novel compressed into 3 vivid sentences:

“A man sitting in a coffee shop all day, running an empire from just his phone. A new one delivered every day by an associate. He is the central node.”

“That’s it,” Robin says. He smacks lips in a half-joking, half-serious way and his eyes twinkle like he’s found real treasure buried under an amusement park pirate ship. “It’s got the taste.”

The taste. Robin’s on the hunt for things that have it—words, phrases, ideas, that have the ineffable thing that makes them good. Some of Robin’s notes are just garbage. But some of them become his building blocks, the atomic units, the bricks that turn into his best-selling novels, his multimedia projects, or the olive grove that he runs with his partner.

But the interesting thing about Robin is he doesn’t look at these things as bricks exactly. They don’t combine together in predictable, linear ways.

Instead, Robin’s notes are more like ingredients—deep yellow saffron, Ceylon cinnamon, black garlic, and white truffle—bits of the world that he throws together into a pot and covers with a heavy lid. He turns up the heat, he adds salt to taste—until out comes a story.

When we talked, I was interested in how Robin organizes his voluminous collection of notes, but I was really interested in something else: what gives a note that taste?

“I honestly don’t think I can say. If I could describe fully what makes a note special there’s a sense in which I wouldn’t need it anymore. The description that captures it fully, is the same as the note. This whole process of note-taking is a very gradual process of me finding my way towards something."

These are Robin’s answers as told to Dan Shipper, edited for length and clarity.

Robin introduces himself

My name is Robin Sloan. I'm a fiction writer – I’ve written the novels Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, and Sourdough – and a media inventor.

I pay my bills by writing novels, but I’m currently designing and creating a video game – and I also work with my partner making olive oil.

I create content, but I play with the content’s container, too

I describe myself as a ‘media inventor’, which I know sounds like a strange label. To me, it means that a lot of my work – not really my novels, but almost everything else – involves inventing a format or container at the same time that I’m writing or imagining what goes into it.

This might be because I’m a member of what some people call ‘the Oregon Trail generation’ – those who played Oregon Trail on Macs when we were in elementary school back in the late ‘80s. We grew up with computers and the internet, but in a way that was kind of in-between our parents’ generation, who had the internet dropped down on them like a ton of bricks, and people younger than us, who grew up in a world where the internet was everywhere, like oxygen or sunlight.

I learned from using those Macs early on that form is always malleable. This became even more apparent when the web came into the picture. Think about it: there’s no way to make a web page or a blog that is not an act of playing with its form at the same time as you're creating its content. So it just seemed natural: the world was always telling me that you worked on those two things – the container and its contents – together.

I take notes by hand, and I take a lot of them

For more than a decade, I’ve been very committed to taking notes by hand, usually in a little notebook that I keep in my pocket. At this point, I need to stop buying those Field Notes notebooks because I must have a lifetime’s supply of them stored up.

When you’re the kind of fiction writer that I am, you're constantly thinking of things, seeing things, reading things, overhearing things – and it turns out that how you take notice of those things can be really valuable in ways you can’t necessarily predict. You have to save that stuff, because you have no idea how it might be useful later.

I’m also devoted to what I think of as my ‘happy pen’ – a super-cheap one you can get from Muji. I have boxes and boxes of them. It’s a 0.7mm, capless pen, and the body is transparent, which I like, because you get to see the ink inside. I’ve tried a lot of basic pens, but this one is my favorite by a pretty wide margin. I stock up on them too, because when I don't have one and I'm stuck with a different pen, I actually feel a little off-kilter.

I don’t have my system for taking notes totally figured out – it actually ebbs and flows all the time – but the important thing is that I take a lot of them.

I transfer my notes from paper to nvALT

Many years ago, I realized that I wanted to get serious about saving all those notes digitally. I didn't want my notebooks to just get thrown away or stuffed into a box – I wanted to preserve them in a way I could access. So I started to use a little program called nvALT, which is a very fast note-taking program for the Mac.

Transferring my notes from notebooks into nvALT is a process that I always enjoy. When I fill up a physical notebook, I'll go through it, acting as a sort of loose, first filter for the material I’ve accumulated. I’ll cross out a few things that are obviously garbage, but most of my notes make the cut, and I transcribe them into nvALT.

When that’s done, I throw away the notebook.

Noticing things that have that special... taste

As for what I take notes about, maybe because I’m a fiction writer at heart, a lot of the things I notice have to do with language.

For example, if I run across an amazing name of a person or a company or a street, I’ll record that for sure. Likewise, if I’m reading a book or something online, and I find a sentence that's evocative or strange – or one that I wish that I had written – I’ll save that, too.

That explains maybe 80% of what I capture. The rest is made up of things – either from the outside world or from the meanderings of my own brain – that have a certain ineffable taste to them.

That ‘taste’ is a very personal thing, and I don’t think I can really explain it. But I’m pretty sure it means that, for me, note-taking is a very long-term, gradual process of finding my way towards something; I just can’t quite articulate what that something is.

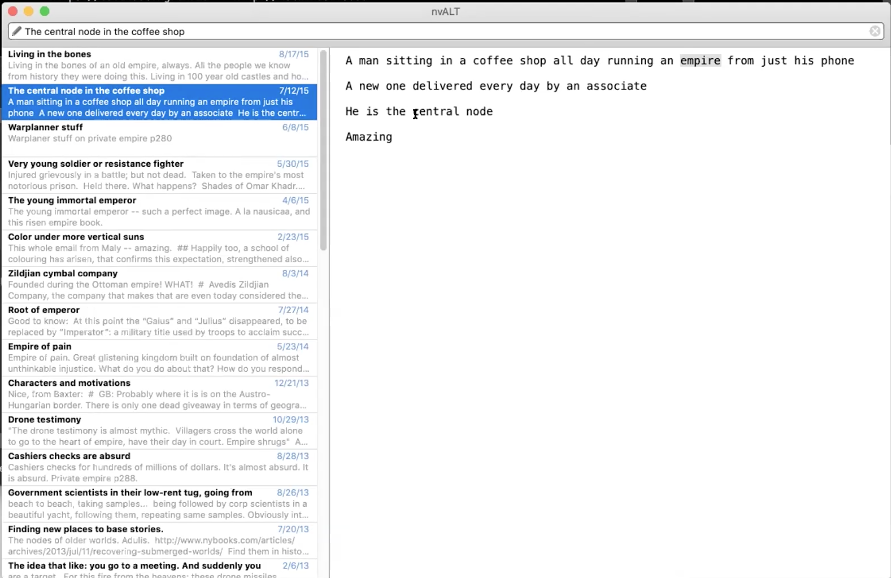

Here are some examples in nvALT of things I recorded because they have that special something I’m always on the lookout for. I must have thought of this and written it down back in 2015 and saved it:

‘A man sitting in a coffee shop all day running an empire from just his phone

A new one delivered every day by an associate

He is the central node

Amazing.’

That's got the taste, for sure. Part of the reason it’s so appealing to me is its story potential. I just want to know more about that idea – it’s like it has ‘story juice’ or something!

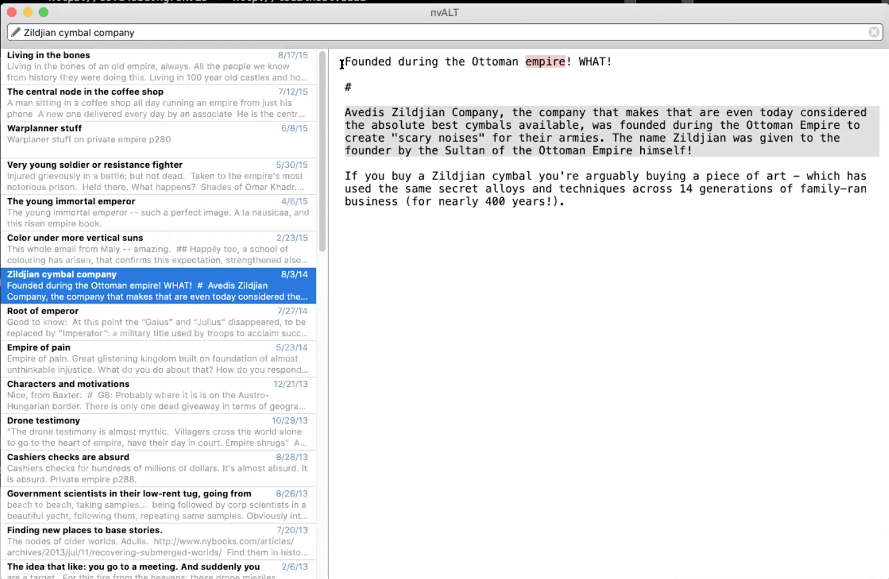

This next one is great. I must have copied this from somewhere: the Zildjian cymbal company, which of course I remember from band back in high school, was founded during the Ottoman Empire!

I’d say that at least 50% of what I collect would be about words and language, like this note, that says that ‘cutthroat compounds name things or people by describing what they do’:

Those are just random examples – and there are thousands more.

How I use my notes

I interact with my notes in three different ways.

Sometimes I simply search through them by keyword or topic to find items that may be useful for whatever I’m working on at that moment. One nice thing about nvALT – the main attraction for me – is that it makes it very easy and fast to search. It's a wonderful kind of interaction where things just appear suddenly in front of you as you're typing in the search window.

For example, the keyword ‘empire’ would have brought me to both the entry about the man running an empire from his phone, and that one about the cymbal company founded during the Ottoman Empire.

It's also a pretty regular occurrence for me to just browse through my notes in a completely random fashion – it’s something I'll do over a cup of coffee. Sometimes I do it just for fun, but usually it’s because I’m working on something and I want to have some raw materials rolling around in my brain.

Here, as I randomly riffle through my notes, it turns up a quote from Oliver Sacks:

I find that random searching like this has a lot of power to create unexpected connections in my brain; it can almost be like consulting the I Ching. In my experience this kind of searching really works, and it produces interesting results.

The third way I interact with my notes is a mechanism I’ve engineered whereby they are slowly presented to me randomly, and on a steady drip, every day.

I’ve created a system so random notes appear every time I open a browser tab

I like the idea of being presented and re-presented with my notations of things that were interesting to me at some point, but that in many cases I had forgotten about. The effect of surprise creates interesting and productive new connections in my brain.

In order to do this, I’ve put some of my programming skills to work to engineer a kind of Rube Goldberg-y system: as I mentioned previously, I export my notes from nvALT into Simplenote, and just basically use that as a back-end database. That export then gets loaded into a server that I’ve set up to feed me a random note every time I open a blank browser tab.

Here, I’ve just opened a new tab in Chrome, and my system automatically pops up a note that I took down in February 2015:

I actually remember this note! I love it: it’s an idea I had ‘about a spy who fled his deep cover and misses his little house terribly… That fantasy of running away. The go bag. Go. That was always a possibility; always the way it was going to end. And now I miss that house. My plates. The basket where I kept the bread.’

It’s the beginning of a story – who knows how or why that occurred to me, but it did. I wrote it down, I digitized it, and now it’s still here and maybe it'll become something one day.

There’s no hierarchy in any of my organizational schemes (and there’s a reason for that)

There’s no hierarchy to this, as you can see. Partly it’s my nature as a person: I have never been a hierarchical organizer in any area of my life. I never had folders for every class in college, and I don’t really even organize my bookshelf. Even my physical writing workspace, though not literally a pile of garbage, is covered with different projects and things.

But there is also a philosophical basis for this which to me is quite practical. A pretty good master analogy is that it’s an attempt to make a big stew pot out of my brain – there is tremendous value in allowing all of these notes and ideas and observations to stew and ferment in there.

For me, the real power comes when ideas intermingle and I’m able to discover connections that I truly could never have dreamed of under normal conditions. In both of my novels, there are things side-by-side on the page that came from two or more of my notes juxtaposed in ways that I could never have imagined at the time I was writing them down.

When I get momentum with my work, I let it take over

How and when I get work done during the day really changes over time, and it totally depends on what project I'm working on. With my novels, anyway, I don’t generally have external deadlines, so my work is usually self-directed.

I've observed for myself that not all weeks of writing are made equal. When I do try to impose a schedule on myself – like resolving that ‘I'll write for three hours every day and hit 1200 words’ – it can work out OK, but it’s usually not that great.

But I have learned that when I’m really on a roll – when I’ve found a voice that’s really working and that I’m excited about – I need to just clear the decks and go with it. I will empty my schedule, dive in, and stay up late in order to be as productive as I can. I would say this is how I got both of my novels written.

If you were to look at a graph of my productivity on both of them in terms of words on the page over time, my output wouldn’t be thin but steady, nor would it ever go down to zero. But you would see these huge leaps in productivity which seem to happen over a week or ten days.

Based on that lived, visceral experience, I’ve tried to pay more attention to the feeling of momentum when I get it, and really lean into it.

Over the last few months, I’ve been feeling stuck in a novel draft I’ve been working on, and so rather than spend my quarantine just struggling against it, I decided to set it aside and instead lean into the momentum I’ve built up in my work on a video game project.

Working in an olive grove helps create space in my brain

I’ve noticed that when I talk about doing creative work, words like ‘stew’, ‘simmer’, and ‘ferment’ keep coming up. Those metaphors really click for me, so obviously they must conform to something important that I have felt in my creative process.

For me, it has been extremely important and useful to create space where a bunch of seemingly unrelated material can get loaded into my brain – into my own personal RAM – and then just hang out in a non-directed, non-goal-oriented way. It can have a chance to stew, simmer, and ferment.

I don't think it's a surprise to anyone to know that there are certain activities that help create that space, and it’s been widely commented upon. Doing the dishes, walking the dog, cleaning the house – you need to be doing something.

For me, pruning trees in our olive grove is perfect. It takes a little bit of attention, but not that much attention. So a whole lobe of my brain can just be bubbling, milling, and spinning away. And I can tell you – good stuff comes out of it.

Two pieces of advice/advice on taking notes

I feel like I say this to a lot of people, especially aspiring fiction writers. In my experience, it is really important to do two things.

One: You have to train yourself to notice things. It's not 100% natural at first – it certainly wasn’t for me – but raising those antennae is a very worthwhile thing to do. And it snowballs: once I got started taking notes, I ended up taking more and more of them.

Two: Be very liberal about what you keep. If you're going through your notes, cross out one thing out of ten, rather than nine out of ten. Don't be too quick to dismiss ideas: you have no idea how material might be useful in the future. Something that may not seem like a great idea now may really bear fruit down the road – even years and years later.

This article was co-written by Dan Shipper and Kieran O'Hare.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!