You enter your kitchen for a quick lunch: how is it exactly that your brain solves the problem “prepare lunch as efficiently as possible”?

Your brain effortlessly, almost instantaneously “assembles” a diverse mix of problem-solving resources on the spot. These “resources” can include knowledge, tools, or structures, and can be:

- Mental: knowledge, experience, intuition

- Physical: tools, environments, objects, visuals

- Informational: instructions, diagrams, data

- Biological: hands and fingers, limbs, the senses

- Audio: sounds, songs, words

- Social: relationships, communities

As you prepare your lunch, you are drawing on the informational resource of the printed recipe. But you may also lay out the ingredients you’ll need as you read, “storing” the sequence of actions you’ll take via their physical location. You may keep a count of how many eggs you’ve added by muttering under your breath, tracking this information using an auditory resource. You are also drawing on many mental resources, such as the meanings of the words you’re reading, common cooking conventions, and basic math to convert from liters to cups. You may ask your roommate where the seasonings are, or call your mom for her famous roasting tips, which are social resources. And of course, you are using your biological resource, your body, every step of the way to accomplish all of the above.

It’s very difficult for us to appreciate what an astonishing feat all this is, because we do it effortlessly. We are inventing, on the fly, not only new ways of using these resources, but new ways of using them together. Our brains have evolved to treat the external world not only as a problem space, but as a solution space.

What’s important to notice about this process is that it is soft assembly. “Soft” because the ways in which we use these resources are not fixed. Our brain brings them together in complex, yet elegant relationships that can change day to day, or even minute to minute. By soft-assembling our tools, instead of physically attaching them together or building a “cooking machine,” we remain far more flexible. We are able to explore trajectories through “thinking space” that wouldn’t be available through rigid approaches.

THREE PRINCIPLES OF COGNITIVE EXTENSION

We are in the midst of a revolution in cognitive science. One of the most exciting frontiers is a shift in our understanding from “embodied cognition” (the body is essential for thinking), to “extended cognition.”

Here’s a definition:

Extended cognition (n): a process centered in and managed by the biological brain, which includes outward loops into the external environment as essential functional parts; a network of problem-solving activities that promiscuously criss-crosses the boundaries of brain, body, and world.

We are beginning to understand ourselves not just as minds in brains in bodies. Our minds are also directly embodied in the external world itself. Our thinking is both grounded in the environment, and distributed throughout it.

This article is my summary and interpretation of the book Supersizing the Mind (Affiliate Link), by Andy Clark. It is a bold (though very long and dense) trek deep into the heart of the most recent research in situated cognition, robotics, child development, and emergence, among other fields.

The science of cognitive extension as it currently stands operates on three core principles:

- Principle of Ecological Assembly

- Principle of Cognitive Impartiality

- Principle of Motor Deference

#1 PRINCIPLE OF ECOLOGICAL ASSEMBLY

The first principle states that our minds are ecological control systems. We are natural-born environmental engineers. We achieve goals not by micromanaging every detail, but by relying on existing structures in the environment around us.

Consider what makes a fish an incredibly efficient swimming machine. The fish is not a good swimmer in isolation. It has evolved to adapt its swimming behaviors to the pools of kinetic energy found in its environment: swirls, eddies, vortices, currents, tides, waves, etc.

The reason this is environmental engineering, not just adaptation, is that it includes both external events (an unexpected swirl or rock in the river) and self-generated ones (a well-timed flap of the tail). It is the environment and the fish together that make up the swimming machine.

As humans, we have far greater abilities to shape our environment, which we’ll discuss later.

#2 PRINCIPLE OF COGNITIVE IMPARTIALITY

The second principle states that our brain doesn’t care whether a piece of information is internal (stored in memory) or external (stored in the environment). It will access whichever source is more reliable, even at the cost of accuracy.

Some experiments suggest that, all else being equal, the brain actually prefers external sources, because they take no energy to maintain.

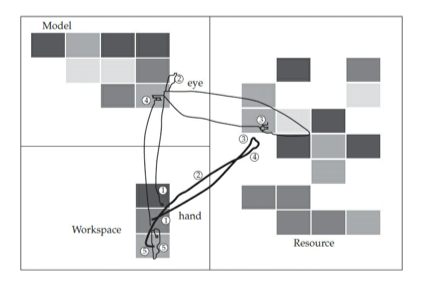

In Ballard et al. 1997, subjects were asked to replicate a pattern of blocks by moving them from a “resource” area to a “workspace” area. The researchers used eye-tracking technology to determine how much they relied on their short-term memory, and how much on the visuals in front of them.

When asked, people will propose a straightforward strategy: look at the position and color of each block, one at a time, and temporarily store that memory to move the right block to the right location, before moving onto the next one.

But this is not at all what subjects actually did. They instead used saccades (rapid, scanning eye movements) to repeatedly check the model, and many more than you might expect. In a followup study in which the color of blocks was changed when the subject wasn’t looking, their hypothesis was confirmed: with each saccade, only one piece of information is stored — either the color, or the position. To retrieve the other piece of information, another saccade is used.

The implication of this is profound: even for one tiny, extremely simple piece of information, our brains seem to prefer repeatedly checking an external source, rather than storing it in memory for even a moment. This suggests an answer to the classic question in knowledge management: which knowledge is worth capturing outside our head?

The answer, neurologically speaking, seems to be: everything.

#3 PRINCIPLE OF MOTOR DEFERENCE

The above conclusion leads us to the third principle, which says that the duality of mental processes vs. physical processes is an illusion, at least when it comes to practical problem-solving. Our mind actively trades off eye movements, head movements, and memory load against each other to minimize what it has to remember.

Our brain “outsources” memory to the external environment, retrieving it back “just-in-time” only when needed. It will do this even when it takes substantial physical effort to do so.

Think of a bartender preparing drinks. Taking a list of drink orders, she could easily remember who ordered what if she wanted to. Instead, she positions the glasses in the correct order on the bar, using their location in space to “remember” the orders. This lightweight offloading strategy is less error-prone, makes her actions more efficient, and allows her to dedicate thinking to other things.

SELF-ENGINEERING

What all these principles suggest is that it isn’t the quality or quantity of our knowledge that matters. Nor even our raw intellectual ability. All these pale in comparison to the problem-solving capabilities of our environment. The bottleneck on human performance is our context.

Luckily, context is not fixed. As natural-born cyborgs, we can change not only what we think about, but how, when, where, and with what we think. We have the natural ability to sculpt and guide our own processes of learning, recall, representation, and attention. For this we use language, physical objects, mental models, the minds of others, our environment, and whatever else we find at our disposal.

Human minds and bodies are designed to undergo episodes of deep, transformative restructuring. During these episodes, our mind can change how it operates. New kinds of knowledge can be incorporated, and obsolete kinds ejected. We can redraw the very boundaries around the “self,” incorporating new tools into the fabric of our cognition.

In my favorite paragraph of the book, Clark says:

“We do not just self-engineer better worlds to think in. We self-engineer ourselves to think and perform better in the worlds we find ourselves in. We self-engineer worlds in which to build better worlds to think in. We build better tools to think with and use these very tools to discover still better tools to think with. We tune the way we use these tools by building educational practices to train ourselves to use our best cognitive tools better. We even tune the way we tune the way we use our best cognitive tools by devising environments that help build better environments for educating ourselves in the use of our own cognitive tools.”

There is no solid ground here. It is supporting structures all the way down.

HUMAN PERFORMANCE

Cognitive extension changes how we define human performance. It proposes that human performance is centered on, but in no way limited by the biological brain.

Instead of putting that lump of soft tissue on a pedestal, we should focus instead on building enabling contexts. On helping our minds make more effective tradeoffs between mental, physical, and social sources of knowledge.

As I’ve argued previously, each one of us is not a single, self-contained entity, but a network. You are not the processor on a computer; you are the internet. Our cognition is best understood not as a “central executive,” but as a “neural economy.” All kinds of knowledge, internal and external, swirl around us constantly, soft-assembling into temporary coalitions to extract value from the environment.

Our consciousness is not just embodied — it is embedded in our environment. Our consciousness is distributed, simultaneously deeply integrated and loosely coupled. Extended cognition is not a shiny new thing we need to “invent.” It’s been essential to our nature for tens of thousands of years.

EPISTEMIC SKILLS

All this has implications for anyone wanting to “build a second brain.” This includes anyone seeking to extend any part of our cognition into software programs, cognitive prosthetics, or even simple note-taking systems.

Consider this famous exchange between Nobel-prize winning physicist Richard Feynman and the historian Charles Weiner. Weiner came across a batch of Feynman’s notes, and commented that they represented “a record of [Feynman’s] day-to-day work.”

Feynman reacted with unexpected sharpness, “I actually did the work on the paper.” Weiner responded, “Well, the work was done in your head, but the record of it is still here.” Feynman pushed back, “No, it’s not a record, not really. It’s working. You have to work on paper and this is the paper. Okay?”

What Feynman was pointing to is something that all tool-builders would do well to remember: our cognition is already extended. We don’t need new, rigid tools. What we need is better mental models, practical techniques, and training to improve our epistemic skills.

Epistemic skills include all the meta activities to shape the information we consume: sifting, sorting, summarizing, classifying, selecting, reidentifying, and comparing.

Take Accountant Ana as an example.

Ana reviews the books she’s preparing, following the trails she’s created through the numbers. She creates and modifies these trails as she goes along, leaving traces on the pages every time she obtains an intermediate result. These traces are visited and revisited on a just-in-time, need-to-know basis. Small bits of information are shunted in and out of memory, much like a computer shifts bits between the hard drive and memory.

Without using any modern technology, Ana is deftly dovetailing dozens of resources, including biological memory, motor actions, external storage, and just-in-time perception.

Her bottleneck is not the sophistication of the technology she’s using. Implementing her system in software would actually erect barriers to her intimate understanding of the numbers.

What Ana needs is an “enactive framework” — a mental model paired with practical techniques — to systematically improve her epistemic skills. This framework would help her unbundle her higher-order mental activity into lower-order kinds of thinking that can be handled by her tools.

Unburdened by lower-order thinking, her conscious mind is then free to ascend to new heights.

Follow us for updates on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!